- Large Buildings

- Posted

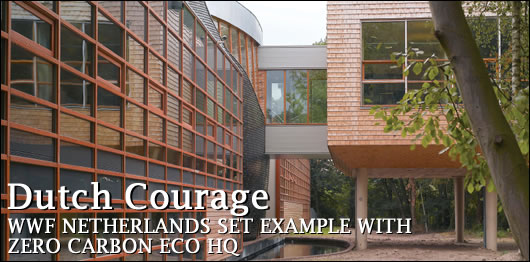

Dutch Courage

Completed in October 2006 the headquarters of the Netherlands chapter of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is nothing if not a striking building. It also happens to be one of the single most sustainable buildings created in recent years. Construct Ireland continues its series of examining internationally significant sustainable buildings, with Jason Walsh putting questions to the building's architects, Amsterdam-based RAU.

In 2002 WWF Netherlands held a competition to redevelop its existing building. RAU's winning entry is the end result of that process.

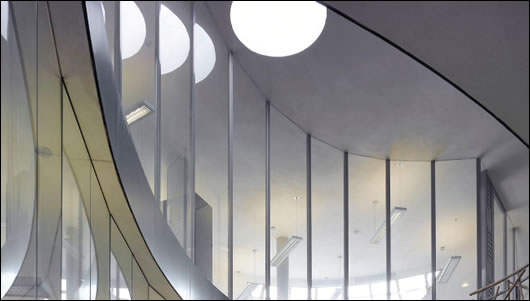

The building's form is quite clearly inspired by organic forms and the desire to reflect the WWF's work in the natural realm. More than that, though, it seems to draw inspiration from the ideas of anthroposophy – something also seen in the past work of the project's architects, RAU, notably with the ING Bank offices in Amsterdam which also happens, like the WWF headquarters, to be an autonomous building. The central 'blob' – yes that is what it's called – houses the building's entrance concourse and meeting room area while, externally, softening the modernist-inspired lines that run outward from it.

Nevertheless, the building's claim to sustainability does not come from aping nature in its form, but rather from a deep and thoughtful commitment to thinking about how a building is used, who its users are and what its impact will be.

Claimed to be the world's first zero carbon building, the WWF headquarters is not only naturally ventilated but also obtains its heat requirements from staff and equipment in the office while solar arrays provide electricity and hot water. A backup biomass system is also in place.

That the building is actually a renovation is most surprising, given the strong commitment not only to sustainability but to the creation of an aesthetic form which marries the purpose of the organisation that inhabits the building.

In fact, renovating existing buildings rather than demolishing them is very much in line with the thinking of RAU.

The central "blob" was clad using variously tinted slates made from baked river clay

The annual energy requirements for heating are provided by the presence of people, the use of equipment and passive solar gains, whilst extensive glazing and roof lighting also reduces the need for electrical lighting,whilst walls and ceilings are plastered with tadelakt (Moroccan lime plaster) and clay

Founded in 1992, by Thomas Rau, RAU Architects is an Amsterdam-based practice which claims a process-focussed and people-oriented approach to architecture, perhaps best encapsulated by its statement: "a building involves more than a roof and four walls." For RAU sustainability is a central tenet of the architectural profession and, indeed, for the practice energy-producing buildings are the norm.

Construct Ireland: How did you come to a low energy strategy for the building?

RAU: Low energy strategies are inherent to our way of building. We acquired the assignment by way of an architectural competition: to redevelop the existing building and grounds.

For us every assignment starts with an inventarisation of the locality (peculiarities, possibilities, history), the people involved (end-users, contactors) and the means (financial and technical). These create an interwoven triangle of boundaries; the space (in terms of ideas) within which the eventual building has to find its form – Gestaltfindung.

What comes first? Design (form, function) or energy concept? None [of these]. These are as many sides of the same coin. 'Sustainability' is not something like gravy that can be put on the potatoes after we have decided to mash them or not.

Every time we present a design we present an energy-concept and vice versa. We will not have it otherwise. And they are always particular for this place, this time, these people. It is as simple as that.

Making a design for end-users involved in nature, fighting carbon pollution wherever and whenever they can… Designing a building for the WWF was for us the perfect match.

CI: It has been claimed that this is the world’s first zero-carbon building. Could you elaborate on that?

RAU: It uses no fossil fuels at all. We worked from a tripartite strategy.

Keep what you’ve got: store warmth emitted by humans and machines; cool with the water that is afterwards used for flushing; regain heat before exhausting air; store heat in the earth; reclaim solar energy from the networks;

Reduce the energy needs: reduce emissions (for example triple glazing, [a] heat pump stores excess heat in the earth, warmth from the used air is re-won before it is emitted); reduce needs (lots of daylight, orientation [towards] the sun, sun blinds);

Produce your own energy: photovoltaic cells produce enough solar energy to cover all the basic needs. The excess is forwarded to the network and can be reclaimed as needs be; [use of a] heat pump; for emergencies there is a combined heat and power generator operated on linseed oil – which has not been used so far.

It is hard to produce figures as the building has not been in operation for a full year but [to provide] some illustrations: up till now the balance of energy delivered to/asked back from the networks is positive. That is to say the WWF building has produced more energy than they needed; we were there during summer and they felt the south side was cold. This is a south façade almost completely covered in glass. The sunshades and the triple-glass kept the heat more than adequately out. So we de-activated the cooling somewhat; we were there in November and they were still busy cooling the building. Heat from humans and PCs more than covered the [heating] need.

CI: Do you feel that this 'off the grid' heating is a model for future building?

Absolutely. See the former question and to elaborate on another point: in almost all our existing buildings (we introduced this Swiss technique in the Netherlands in 1996) we have opted for concrete core activation as a means for heating – and cooling! One makes optimal use of existing sources: the building’s mass, the warmth of humans (and machines). The temperature is stable (24 hours a day!) within a comfortable range which is healthier. It causes less dust circulation. It makes it possible to reduce the building volume (no suspended ceilings and no radiators).

Our innovation for the WWF has made it possible to apply these advantages to existing concrete structures. The use of great volumes of mud brings additional advantages: acoustic improvements; humidity levels are regulated naturally; more inner mass (15 silo of mud making it possible to use more glass in the facades).

But the most important point to make is the issue of design strategy: [creating] buildings made to measure, designing for this particular location using all its natural resources, like sunshine, natural shading and so on.

CI: In the building you use a fair amount of 'low-tech' solutions to energy issues such as relying on people for much of the heating. Was this a conscious reaction against high-tech eco solutions?

RAU: We do not reject high-tech per se, but what we are looking for is sustainability on all levels, which implies also the operation and maintenance of the building. This is easier to guarantee in solutions kept as low tech as possible.

The facades for the office space use FSC certified Oregon pine frames and awnings

One could say that two of our slogans have been: high-tech solutions by low-tech means. State of the art is our point of departure (not our ambition).

[In terms of] synergy: we aim to solve much of the energy needs of the building within the design/construction. Aesthetic, social, financial and technical considerations are treated as different aspects of essentially the same problem. This means that technical advisors (construction, installation, interior, landscape, art) join us in a very early stage of the design process.

Photovoltaic panels provide the bulk of the building's minimal electricity requirement

Every time we try to look afresh at the problems that confront us: making the sun blinds go up instead of down saves 70% on artificial light use in the offices (developed for Triodos National Bank in 1999 – a project which gave us a ministerial award for being a ‘model project of sustainable and energy-efficient building’); giving the WWF a facelift that is also a sun-blind; using the ponds at the entrance of the WWF as a source of daylight for lighting the entrance hall (reflection). Every new project is seen as a chance to learn and develop.

CI: Does it work?

RAU: Yes!

CI: Some economists and environmentalists have argued that we will need to entirely rethink how we live including the clustering of business, industry and offices. Do you agree or does the WWF building indicate a possible rapprochement between environmental issues and the need for larger buildings?

RAU: These are separate issues. It may very well be the case that we will have to rethink the way we live and work. Global warming will have an enormous impact, but there are other considerations too - growth of the world population and technology, to name a few.

For us the WWF actually shows what we have claimed was possible for a long time. That it is feasible to create buildings that are healthy (healthier), that produce energy (this one produces at least as much as it needs for itself) and that do not contribute any CO2 to the atmosphere. This is possible regardless of how one thinks and feels about the world development, and it is realisable within normal budgets.

Put differently: the WWF demonstrates that there is no longer any excuse to put off a zero-carbon energy producing strategy!

CI: Does RAU specialise in sustainable architecture?

We feel the question is falsely put. It suggests that one could – from a moral perspective – engage in anything other than sustainable architecture. An example may make this clear: “Do you specialise in cars that are committed to the current standards in safety regulations?”

Sustainable architecture is currently used as a sort of marketing tool, and it shouldn’t be. The public should have a natural guarantee that their architects and builders supply them with the state of the art in sustainable building. That should be part and parcel of their profession – as it is of ours.

The offices are accommodated in the east and west wings with facades incorporating transparent and dark grey tinted glass

CI: Does the building’s commitment go beyond energy use for heating, cooling and lighting into, for example, examination of the embodied energy in the construction?

RAU: Yes. Our point of departure was to re-use as much of the existing materials as we possibly could. We were as sparse as we possibly could in ordering - our solutions were aimed at letting the same material fulfil more than one function (synergy).

Furthermore we checked and re-checked all the materials we ordered.

Some examples: all materials were checked by the WWF worldwide network on how they were produced (to eliminate any child labour); all rubble we did get from the necessary demolition was re-used to make a parking space; we used clay and gravel from Dutch rivers: materials won to give the rivers more room.

[This is] space they need as a result from global warming. The floor mat is made of old car tyres, the carpeting of recycled textiles. We integrated space for animals, ponds at the entrance double as source of daylight in the hall (reflection) and as a safety measure against breaking and entering by way of driving heavy vehicles through the glass entrance. In the near future all water – including sewer water – will be cleansed and re-used ([for instance by] flushing the toilets) on their own grounds.

See also the next question.

CI: The wood used in the construction was Forest Stewardship Council Chain-of-Custody approved. Was this for primarily environmental reasons or were you attempting to marry environmental and socio-economic issues?

RAU: Both. We used for example platonised local woods. These are woods that have been heated, during which process they have lost most of their flexibility but have become as durable as teak. These are fast growing and local, saving us a lot of money in buying costs, transport and maintenance (painting) as well as saving a lot of energy.

A paradoxical point to make: the FSC hallmark has been developed to save tropical forests. For that reason some local (Dutch) wood doesn’t carry this mark. What if your contractor demands you use only woods with an FSC mark – should you import all your woods from the tropics?

CI: Did working with natural materials such as clay and lime raise any issues during construction

RAU: No. You need professional skill, but the same applies if you use other materials. There [are] still a lot of these skills to be found in places like North Africa, Mexico and the Middle East where they have used these techniques from times immemorial. In Holland more and more professionals are 'turning up' in response to a growing demand.

CI: Do you perceive, or indeed did you plan for, any potential health benefits with the building?

Yes: more daylight, orientation [with regard to] the sun in accordance with type of work. Dust circulation [is] greatly reduced ([protecting against] lung problems like CARA, [and effects on] contact lenses), better acoustics, humidity regulation (CARA, contact lenses), 'normal' temperatures ('air-conditioned' summer colds), no chemicals [are] emitted from carpeting or otherwise, no chemicals [are] needed for cleaning and maintenance.

CI: Did you feel that a strong commitment to sustainability raises any additional challenges for architects, specifically in terms of aesthetics and form?

RAU: The special challenge lies in bringing all parties – all engineering disciplines – to the table from the first; making them forget their previous lines of thinking and getting them to start thinking from scratch instead. The solutions will be inventive and/or innovative. They can be even more aesthetically [pleasing] as the technique is fully integrated in the design.

The resulting gestalt could be said to have – like a person - many faces, depending on the perspective one takes: aesthetics, health, energy, buildings costs, operation, maintenance, stimulating work environment, and so on. Every time one changes perspective one gets another angle [on] the result. But whichever angle one takes, it always has to 'fit'.

So: additional challenges in bringing people together and making them think afresh; the gestalt is the result of a lot of simultaneously processed considerations; we create synergy: solving different issues by the same gesture (such as mud for warmth storage, acoustics, humidity, and so on); leaving us more – not less – room for the purely aesthetic perspective.

CI: Was there an interaction between the client’s raison d’être and these aspects of your design?

RAU: Yes, a great deal.

[In terms of nature], we aimed to make the use of the building as efficient as we could so as to give part of the build environment back to nature. We integrated room for animals in the building (bird’s tiling, bat basements).

[In terms of finances] the WWF is supported by donations. These donations are for wild-life preservation. So we tried to be as sparing as we could with the donors’ money. Keeping an existing structure and upgrading it has provided them with good value for money.

For the WWF people this was very important: they were always on our back not to spend too much money, [not to] make it more luxurious than needs be. The need to spend every euro on animal life is heart felt. And they did get good value for their money: the property made such an increase in value that the current taxation/property value exceeds the combined costs made in acquiring and rebuilding.

CI: How does the building’s form relate to the desire to ecologically sound?

RAU: We feel that each building should be the outcome of a communication process between three factors: the genius loci, the people involved (potential end-users, contractor) and the moment in time (state of the art in technology, budget, and so on). Change any one of these factors and another kind of building would have emerged.

Put differently: in our view style is not the starting point of the process. If we have a 'style' it is found in the quality of the process.

The gestalt is thus the outcome of this process involving these different aspects (people, planet, profit – locality, users, a particular moment in time).

Therefore: 'form' and [being] 'ecologically sound to the best of our abilities' are inextricably bound to us. It is like a tapestry – does the weft define the warp?

- Articles

- Large Buildings

- Dutch courage

- RAU

- World

- Wildlife

- fund

- WWF

- Netherlands

- low energy strategy

- zero carbon

- photovoltaic

- sustainable building

Related items

-

Enniscorthy to host ‘make or break’ sustainable building summit

Enniscorthy to host ‘make or break’ sustainable building summit -

Much ado about nothing

Much ado about nothing -

Embodied carbon & zero emission targets adopted in new EPBD

Embodied carbon & zero emission targets adopted in new EPBD -

Scotland committed to continuing passive house journey

Scotland committed to continuing passive house journey -

Scotland to mandate passive house for new homes

Scotland to mandate passive house for new homes -

Roadmap targets embodied and operational carbon

Roadmap targets embodied and operational carbon -

Techrete aims for net zero carbon by 2030

Techrete aims for net zero carbon by 2030 -

LETI: 33,000 net zero carbon homes planned

LETI: 33,000 net zero carbon homes planned -

Scrap EPCs to unlock deep retrofit market, MPs argue

Scrap EPCs to unlock deep retrofit market, MPs argue -

Ballymore to deliver mooted zero carbon Guinness Quarter

Ballymore to deliver mooted zero carbon Guinness Quarter -

New issue of Passive House Plus free to read

New issue of Passive House Plus free to read -

Getting to net zero carbon

Getting to net zero carbon