- Large Buildings

- Posted

Industrial Revolution

It’s not often you find an industrial facility that combines low carbon construction with emphasis on natural materials, occupant health and energy efficiency, but Rehan Electronics’ new Wicklow factory is no ordinary building. Lenny Antonelli paid a visit to what must be Ireland’s greenest factory.

Industrial manufacturing and sustainability don’t always sit well together, but a new factory in Carnew, County Wicklow, is eroding barriers between the two. The new home of Rehan Electronics, makers of devices for the visually impaired, has enough green features to make it arguably the most sustainable industrial facility in the country.

Boasting poroton block walls, a wood chip boiler, five mechanical ventilation heat recovery (MVHR) units, sheep wool insulation and natural paints, the building was the vision of Rehan’s Jan Vreenegoor, who managed the project himself. “It was quite difficult to find builders capable and willing to build this,” he says. “There were too many different materials they weren’t familiar with. So we built it ourselves. We took on labourers and trained them on-site,” he says.

An electronic engineer by trade, Vreenegoor has extensive experience from building previous Rehan factories, and his own house. “I know more about building (than electronics) now,” he jokes.

Two large adjacent rooms, spanning a total length of 68 metres, dominate the factory; one acts as the factory floor, the other a storage facility. A first floor timber-framed office space rests on ground floor poroton construction. Ecological Building Systems supplied much of the make-up of the timber walls, including Sasmox gypsum bonded wood particleboard internally, an Intello vapour barrier check, and Panelvent external sheathing board (derived entirely from wood waste). Insulated with 150mm of Sheep Wool insulation, the walls boast a U-value of 0.19 W/m2K.

In the main rooms, concrete wall pillars support the timber trusses that span the width of the ceiling. Keen to reduce the embodied energy of the build, Vreenegoor chose concrete with 80 per cent ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) content from Ecocem. Derived from steel industry waste, GGBS is a cement substitute that avoids the vast majority of the embodied energy of the traditional Portland variety.

Did working with such a high concentration of GGBS pose any challenges? “It can be difficult to get the right consistency, but once you get it right it’s fine,” says Vreenegoor, pointing out new building products inevitably demand some getting used to.

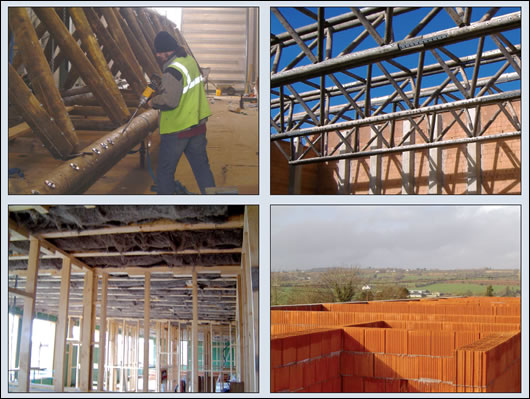

The timber trusses that span the width of the ceiling in the factory floor and storage area are made from FSC-certified Latvian timber

Though the Rehan factory is mostly constructed from poroton blocks, the first-floor office and canteen area is timberframed

Between the concrete pillars, poroton blocks comprise the bulk of the building’s structure. Poroton - essentially clay fired at 1000oc - is an alternative to concrete blocks. Derived from an abundant natural resource, it makes an excellent insulator. “It provides structural capacity, is hydroscopic (moisture absorbing) and has a relatively low embodied energy,” says project architect Mike Haslam of Solearth.

Formula Building Technologies (FBT) supplied the T12 poroton blocks used for the build. The 365mm blocks have a honeycomb network of aerated cavities that provide thermal insulation. The blocks were covered with a lime plaster, and the walls’ u-value is 0.27w/m2K. While this wouldn’t be extraordinary for a domestic build, it’s more than sufficient for a factory with large internal gains from equipment, and little need for internal heat retention at night.

The timber trusses are the building’s dominant architectural feature, and were necessitated by Vreenegoor’s desire to leave the main rooms free of supporting columns. On the factory floor, with its relatively low ceiling and abundant natural light, they are strikingly prominent. “The trusses define the building to a large extent.” Haslam says. Vreenegoor chose timber after considering other materials. “We didn’t want to use steel for the trusses because of the high embodied energy, and we didn’t want to use glulam because of the glue content, and because it’s not recyclable. So we came up with this,” he says.

As with the building itself, Vreenegoor took a uniquely DIY approach to the trusses: “We couldn’t find anybody to build the trusses, so we decided to do it ourselves. Then we couldn’t find anybody to cut the logs, so we figured we’d buy a machine to do it. We couldn’t get the right machine though, so we had to design and build the machine ourselves, and because renting a shed for the year was so expensive, we built a shed to make the trusses in too.”

John Brady of local company Woodfab Timber sourced logs for the trusses from FSC certified forests in Latvia. While Vreenegoor hoped to source timber locally, issues of moisture and tapering forced him to look abroad. “The quality wasn’t available in the length we needed from Ireland,” Brady says. Woodfab supplied timber cladding for the roof and façade too, sourced locally in Wicklow. Vreenegoor insisted that none of the timber elements were chemically treated. “I was wondering what colour the trusses would settle out, but they came out all right,” Brady says.

Intriguingly, the factory floor – the most occupied part of the building – faces north. Its saw-toothed roof features rows of north-facing windows, while the north wall is extensively glazed. With no need for light on the factory floor in the evening, the orientation makes sense. “It’s a better working light, and if it had been facing south there almost certainly would have been problems with overheating,” Haslam says. Glare was another reason for the orientation, Vreenegoor adds, as it can interfere with monitors on the factory floor.

The orientation works. On the dull September day Construct Ireland visited, the factory floor was brightly lit, with only a few fluorescent tubes supplementing the abundant natural light. Upstairs, the office and canteen area faces west. “It means you’ve got the afternoon light coming into the office space, and those rooms benefits from wide views across the countryside,” Haslam says. All windows in the building - supplied by Rationel Vinduer Ltd - are double-glazed, argon filled and boast a low-e coating, with a u-value of 1.4 w/m2K.

Timber trusses dominate the extensively glazed north-facing factory floor, which was polished mechanically, thus avoiding the use of any chemical products or additional materials

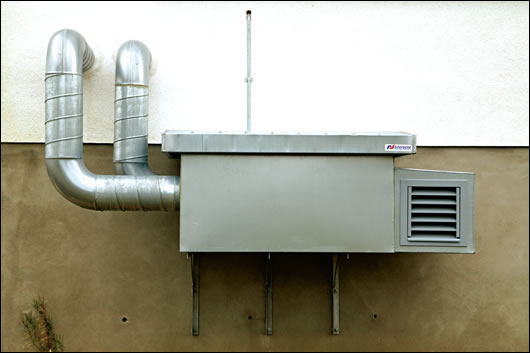

Fumes produced from soldering in the factory are drawn directly from workbenches to a mechanical ventilation heat recovery unit outside

A 100kW HDG wood chip boiler is the factory’s main heat source, with hot water stored in an accompanying 3000 litre buffer tank. Wood chips are fed into the boiler via a spring-loaded sweeping arm, with the rate of supply determined by the burning temperature of the boiler.

“Once the buffer tank reaches a certain temperature, the boiler goes into standby mode,” says Colm Byrne of Glas, who supplied the system. “It’ll stay off until the upper probe in the buffer tank drops in temperature.” While not yet hooked up, the boiler also features a software management system that allows for remote maintenance.

Having considered a ground source heat pump, Vreenegoor eventually chose the boiler. “It works out better economically, and environmentally too, because with geothermal you still have to buy electricity,” he says. Vreenegoor sources his fuel supply from Woodfab’s local sawmill in Aughrim.

The factory's underfloor heating system is divided into eight different zones, controlled through a plant room adjacent to the factory floor

An underfloor system distributes heat throughout the building. Five mechanical ventilation heat recovery (MVHR) units - supplied by Enervent Ireland - supplement this. One Enervent thermal wheel MVHR unit sits outside the building, recovering heat from soldering fumes generated on the factory floor. “We told the suppliers the amount of air exchange we needed, and they designed the system. We installed it ourselves,” says Vreenegoor.

Four further MVHR units supply warm air to toilets, showers and the canteen. The units are automated, only switching on when occupants enter the rooms. Three of the units are Enervent Pinguin 120 thermal wheel recovery units, while the fourth is an Enervent Phoenix 85 unit, featuring a low pressure hot water coil that uses hot water to warm the adjacent bathroom.

The ground floor features a 75mm layer of concrete screed that includes lime filler, a by-product of tarmacadam manufacturing, and Cem2, a cementitious material that includes fly ash, a waste product from coal-fired power stations. While no GGBS was used in the screed, the lime filler bulks up the mix and reduces the amount of cement needed. “The lime filler is a waste product, it would be dumped otherwise,” says Kevin Grehan of Fast Floor Screed, who laid the mix.

|

| Rehan's Jan Vreenegoor says his desire to build a sustainable industrial facility developed from his vision of a factory that would be healthy for employees |

Gypsum based screeds were unsuitable for the Rehan project. “Gypsum is produced at 150oc while cement is produced at 500oc, so there’s quite a carbon saving with gypsum. But because this was a manufacturing floor, it needed to carry quite a bit of weight. We couldn’t do that with gypsum,” Grehan says. Concrete screed was also chosen because it is electrostatically neutral, so it doesn’t interfere with manufacturing processes. Intriguingly, Fast Floor Screed typically bring rainwater collected at their facility in Kildare to site for use in the screed.

To avoid the embodied energy of extra materials, Wexford-based company Renobuild polished the concrete factory floor to give it a smooth, reflective finish. “It’s a mechanical process,” says Renobuild’s Seamus Redmond. “There are no chemicals used in the polishing process, or for cleaning the floor.” Redmond says that polishing also substantially improves the durability of the floor. Redmond points out that additional environmental impacts are reduced indirectly by the concrete polishing process – as is the case in Rehan, it removes the need for laying additional flooring materials on top of the concrete. The floor features 100mm of Kingspan extra high density extruded polystyrene insulation, while a 150mm slab of subfloor concrete includes 70 per cent GGBS.

Inside, the factory was painted with Auro’s range of natural paints, including a chalk paint used for the poroton elements of the build. “The poroton block has a lime plaster over it, and you need a specific paint to go with that,” says Martin O’Mahony of EcoBuild, who supplied the paints.

Bodo Bodewigs of Healthbuild, Auro’s national agent, elaborates: “If you have an alkaline surface like a lime plaster, then it’s always advisable to use an alkaline wall paint,” adding that alkaline paints are also particularly effective at preventing mould. On the timber frame parts of the factory, Auro’s standard water-based wall paint was used. “There’s no petrochemicals in the paints, and all the pigments are natural,” O’Mahony says.

Timber floors in the upstairs area are finished with Auro’s natural hard oil, which contains a variety of plant oils. “The linseed and vegetable oils used have organic certification,” says Bodewigs, adding that Auro sources organically-certified raw materials when possible. “Our goal is keep ecological and health aspects in balance with the technological advantages of the product,” he says. All subsurface pipes in the building are clay. “We wanted to use as little PVC as possible,” says Vreenegoor.

The 100kW HDG wood chip boiler that heats the factory is housed in an underground boiler house

Ridgeline supplied the Firestone EPDM – a type of recycled rubber – used for the roofing. “It can expand and contract in extreme temperatures,” says Ridgeline’s Rory O’Hagan. “And it will always revert back to its original shape.” While it’s common to use adhesives to attach the EPDM, Vreenegoor insisted on fixing it mechanically to avoid the use of chemical adhesives. “It means it can be recycled easily afterwards,” he says. The roof of the factory floor and office space includes 200mm of Sheep Wool Insulation, while the flat-roof of the storage area has 100mm.

The timber-framed area was sealed using air-tight tapes and membranes supplied by Ecological Building Systems. Though the building was not tested, Vreenegoor is confident it is as air-tight as possible. “The good thing about poroton construction is that it tends to be inherently air-tight,” Haslam adds.

Clearly the factory boasts an impressive list of green features (it also has its own compacter for recyclable waste), but Vreenegoor wanted to take things further: the initial planning application included a constructed wetland intended to treat the factory’s wastewater. The system would have included vertical and horizontal flow reed beds, a willow plant percolation area, and urine and solid separating toilets.

“This was supposed to be our chamber of solid separation,” Vreenegoor says, showing Construct Ireland a sheltered outdoor enclave. “Now it’s the bike shed.” Despite two applications, the system was refused planning permission. “We spent a lot of time trying to persuade the planners that it was worthwhile,” Haslam says. “But they weren’t convinced. They didn’t know the system and were concerned about it at an industrial level.”

Electricity supply is perhaps the only facet of the building that hasn’t been addressed, though Vreenegoor points out that extensive use of passive solar lighting has drastically reduced the need for artificial lighting compared with Rehan’s previous factory. He has considered powering the building with a vegetable oil or biodiesel-fueled generator, but reckons that small generators will not be economically viable until feed-in tariffs are introduced.

Having just completed what is perhaps the greenest industrial building in the country, Vreenegoor’s own views on sustainable building have solidified. While believing that low energy building is likely to grow as buyers seek to reduce fuel costs, he’s uncertain as to whether occupant and environmental health will remain priorities. “It’s all (focused on) energy, but now that the economy is starting to bite, I wonder how much attention will be paid further down the line to ecological building?” he says.

(clockwise, l-r) 200mm of Sheep Wool Insulation was installed in the roof of the factory floor, with 100mm in the roof of the storage area; Vreenegoor’s own team of labourers assembled the timber trusses in a purpose-built facility behind the factory; the T12 poroton block walls, concrete pillars and timber trusses during the building's construction; 365mm T12 Poroton blocks comprise the bulk of the building's structure

The Enervent thermal wheel heat recovery unit. Four further MVHR units are installed adjacent to the factory's bathrooms and showers

Vreenegoor lies at the heart of the project’s success, and his commitment to sustainable and healthy building is obvious. “Jan is a rigorous green thinker and doer, and the factory is a built statement to his values. There was no question of skipping or taking shortcuts, we were always impressed with his level of care,” Haslam says.

When the building was first conceived, Vreenegoor says his first priority was to create a healthy working environment for his employees. His green thinking developed later. “As you read up on things, you become more aware of environmental issues,” he says. “Eventually we said, if it’s economically viable to do it, why not?”.

So has it been economically viable? Vreenegoor isn’t sure. He estimates the total cost of the build to be about e3.65million. Haslam says that proving it was economically feasible to build a sustainable industrial facility was one of his main goals on the project. He admits, however, that the finished build is “probably too expensive per square metre” to serve as a perfect industrial prototype. “Economically speaking it would work better on a smaller scale,” he says.

Haslam, nonetheless, is proud of the finished article. “It has a fairly pragmatic, functional layout, and by necessity it’s a fairly modest building. But it’s interesting that you could develop a truss that becomes such a dominant architectural feature. It’s the integration of that low embodied energy technology (the truss) with the passive natural light that forms the dominant aesthetic of the building. For me, that’s one of the triumphs.”

“It’s not necessarily very ambitious in terms of architecture,” he adds, “but in terms of ecological design it’s very ambitious.” Indeed, the Rehan factory is clearly more than just a low energy building. What sets it apart is the detailed attention paid not only to energy consumption but also to occupant health, environmental impact and embodied energy throughout. In going that extra distance, Rehan has given fresh meaning to the term green industry.

Selected project details

Client/contractor: Rehan Electronics

Architects: Solearth Ecological Architecture

Structural/M&E engineers: Buro Happold

Wastewater design proposal: Ollan Herr

Poroton blocks: FBT

Wood chip boiler: Glas

Insulation: Sheepwool Insulation

Particle board, sheathing board and air-tight system: Ecological Building Systems

Natural paints: Auro paints via Eco Build

EPDM roofing: Ridgeline roofing

Roof lights: Solatube

GGBS: Ecocem

Timber for trusses, external & roof cladding & wood chip supply: Woodfab

Related items

-

Is procurement stifling natural building materials?

Is procurement stifling natural building materials? -

The deepest greenest retrofit ever?

The deepest greenest retrofit ever? -

Ireland's new central bank hits nZEB & BREEAM outstanding eco rating

Ireland's new central bank hits nZEB & BREEAM outstanding eco rating -

Norfolk straw-bale cottage aims for passive

Norfolk straw-bale cottage aims for passive -

Ground-breaking housing scheme captures one developer’s journey to passive

Ground-breaking housing scheme captures one developer’s journey to passive -

Welsh school fuses passive & eco material innovation

Welsh school fuses passive & eco material innovation -

East London passive school promotes active learning

East London passive school promotes active learning -

Warm and healthy Devon flats that need no heating

Warm and healthy Devon flats that need no heating -

Ecological passive house built on tight budget

Ecological passive house built on tight budget -

International selection - issue 11

International selection - issue 11 -

Hereford archive chooses passive preservation

Hereford archive chooses passive preservation -

Low energy Tipperary offices go for gold

Low energy Tipperary offices go for gold