Jason Walsh

Jason Walsh

- Policy

- Posted

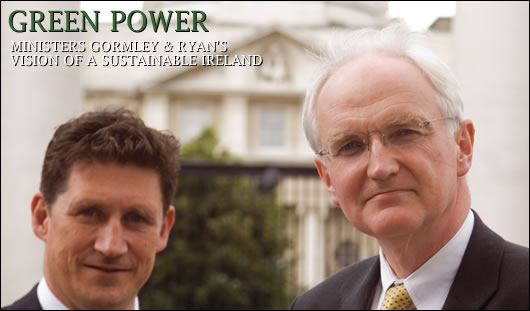

Green power

Perhaps the most unexpected result of the 2007 election was the entrance of the Green Party into a coalition government with Fianna Fáil and the greatly reduced Progressive Democrats. After the resignation of Trevor Sargent as party leader, Eamon Ryan and John Gormley will be leading the Greens in government as Minister for Communications, Energy and Natural Resources and Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government respectively.

Jeff Colley and Jason Walsh met with both new ministers to find out about their plans over the coming years and how they will relate to the construction sector.

Changing environment

Opposition TD, Lord Mayor of Dublin, anti-smog campaigner and verbal sparring partner for Michael McDowell – all of these are descriptions of the former guises of John Gormley. Now the TD from Ringsend, who was elected as leader of the Green Party the day after meeting with Construct Ireland, has an altogether more formal and influential job: Minister for the Environment. As a high-profile Green Party member the environment portfolio is obviously quite a catch for Gormley but the months and years ahead are sure to prove challenging. Whether the Department of the Environment turns out to be a perfect fit for the Greens or a poisoned chalice, only time will tell.

For now the new minister is confident that the Gordian knot that is the often conflicting interests of business, the public and the environment will be sliced through with a dose of supra-national realpolitik.

For example, Gormley is keen to take a wide-ranging approach to emissions that result from construction, an industry that has long been a vital pillar of the Irish economy as well as, according to its critics, a ravaging monster chewing through the nation's resources: "We know, and I've been saying this for years, that domestic use makes a huge contribution to our CO2 emissions. It's not just in relation to how a house is constructed, it's overall planning as well – where the house is located in terms of transport nodes.

"I think it's absolutely vital, going forward, that we get this right. I think, frankly, that it's been a huge missed opportunity going back years. We should have got our house in order a long time ago and what we're trying to do is make up ground."

Asked if, given the likelihood of a slowdown in residential construction, it is now too late to make any meaningful change, Gormley told Construct Ireland that he didn't share such a view: "You could argue – and it has been argued – that it's probably too late in relation to climate change. I'd never adopt that approach. If I thought it was too late I wouldn't have taken up the position," he says. "It does make it more difficult, undoubtedly, and what we have to do is to ensure that we get it right. We also have to look at trying to undo the mistakes that we made in the past and that will mean a huge insulation programme – we've put aside money for that as well."

For Gormley it's not all about fixing the mistakes of the past, he's also keen to avoid mistakes in the future and sees a fundamentally different approach to residential development as a way of not only working to reduce emissions and improve quality of life, but also as a potential lifeline for the construction industry: "One of the things I'm very interested in is the whole eco village concept. Now, I think eco-villages are great because they're all about good planning first of all – a true eco-village would be located close to [public] transport links – it's about having all of the services there on-site and about having good insulation.

Gormley, a one-time director of the groundbreaking Cloughjordan eco-village in Tipperary, is not unaware of the problems that such developments have faced in the past but remains bullish about their prospects for the future: "You've seen the difficulties in relation to Cloughjordan but I want to see that concept being sped-up, I think there's potential there because we have a situation where we could provide top class housing. You could deal with a number of issues together if we fast-tracked the eco-village concept. That's what I'd like to do."

An illustration of the Village, Cloughjordan, where some plots are still available. See www.thevillage.ie for further information, Image courtesy of Solearth

Gormley clearly has the will to do something and it would appear that he has the means. The programme for government refers to e150 million being set aside for community development and Gormley also thinks that the nature of eco-villages could be used to reduce the cost to industry in terms of taxation: "Should the eco-village have to pay the development levies? If you are providing the services yourself should you have to pay that money out? That is a type of funding in itself. You're not funding it directly from the exchequer but what you are saying is, if people can do this then those development levies aren't required.

"My thinking on this is developing all the time, but I have brought it up at a number of meetings saying is there any way that we can do this because, frankly, the timescale for Cloughjordan has been so long – that has to stop. We talk about fast-tracking infrastructural projects, to me fast-tracking the eco-village concept would be the best way of doing it."

Gormley readily admits that the eco-village concept is a relatively new one in Ireland but is optimistic that local authorities will see the same benefits he does: "I would hope that if a direction comes from here that they will respond favourably because what we're about here is providing a new impetus and a new direction. I make no bones about it, this is the direction that I want to go in.

"It's possible to have an eco-village down on the Poolbeg penninsula, but, if you want to go back to the whole transport issue, it's important to have a Luas link or whatever, otherwise it doesn't make sense to start locating communities of any description, high-density or otherwise, if you don't have those transport links."

Of course, Ireland isn't the only country that is re-considering its approach to development. The UK, for example, is currently faced with an enormous housing shortage, particularly in the south east of England and, since 2001 the government has announced plan after plan to deal with the problem, the most recent being the concept of eco towns floated by British prime minister Gordon Brown.

The British government wants to build an extra 250,000 new homes up to 2020, increasing to three million its overall target for the period – a number which could fall two million short of the amount needed in London alone by 2020 – and yet the plans already face tremendous opposition, often wrapped-up in green verbiage. The eco towns plan is an attempt to face off this criticism by building on old, unused state-owned sites, primarily land owned by the Ministry of Defence, but also possibly on National Health Service land. Unfortunately for Brown, the much commented-upon eco towns are increasingly looking like Potemkin villages given that, even if they are actually built, they will still fall literally millions of houses short of what the country actually needs.

Ireland, on the other hand, has up until now seen no shortage of development even if critics are correct when they argue that too little planning has resulted in a real housing shortage, with many houses being unoccupied holiday and investment properties.

Nevertheless, it's easy to see why the perception may exist that a party which focusses its vision for polity on environmental issues would be hostile to development. After all, Gordon Brown's eco towns look rather like half measure in the face of a housing crisis and one that the government was virtually forced into by pressure from groups claiming to want to protect the environment.

Gormley states that this perception is simply incorrect: "I would say that you have to look at the experience abroad. The Green party is not hostile to development – this applies to any Green party, in fact you'll find that in Germany the construction of wind turbines took off to a huge extent under the Green party, construction of solar panels on houses took off. The evidence just isn't there. Construction is part of how we live, it's important and it's just as important that we actually look at how we're living right now and improve on that."

It follows that Gormley sees his rationale for participating in government as the realisation of a desire to get things done: "If we were in opposition next week we'd be achieving nothing, right? Half a loaf is better than no loaf, right? That's the way it is and politics is the art of the possible. We're trying to achieve something here and I've been in opposition long enough to know that no decisions are made in opposition that will affect people's quality of life, simple as that."

When it comes to how the Green ministers will actually act in government, Gormley concedes that the German system of planning and development does provide a model: "Yes, you look at Germany, and look at the planning in Germany for starters, and you say 'Yeah, that's the way to go.' You actually build communities around good public transport, you invest in renewable energy and you create a sustainable future. There are lots of other areas that Germany is very good in as well but even Britain is better than we are, if you want to be honest about it, in planning terms."

John Gormley explains how his policies will come to fruition

In line with his support for eco-villages, Gormley has no dispute with construction per se, but does want to see a more rational approach to planning: "Boom construction is fine [but] I've seen some of the stuff that has been built, I've seen townhouse being built in the middle of bogs and I'm just wondering has any thought gone into this at all? And it has been mindless, frankly, some of what has gone on. There's no concept behind the whole thing at all.

"I have no problem with... great, build – let's build," he says, "but let's build with a bit of common sense. That's where we're coming from. If we have a boom, great, and as far as I can see the predictions in relation the construction industry are that commercial development will continue but we're going to have some slowdown in relation to housebuilding."

As part of his vision for a mode of development that contributes to a reduction in emissions, long-term investment in public transport is vital: "For many, many years I asked: 'Is it going to happen?' It has to happen, that's the point. There are two forces that will come together: one is climate change and the other is peak oil. Put those together and you have a country which is forced to think in a different way. We already have our Climate Change Forum, we're going to have a cabinet committee chaired by the Taoiseach of the country. Therefore, you'll be bringing together all of those sectors and saying 'this is what we're going to do, this is what you're going to do, how are you going to do it' and there'll be an onus on people to provide solutions. It's a big ask, there's no question about it, but it has to be done and when something has to be done, it gets done."

One area of huge importance for the industry and householders is the impending changes to Part L of the Building Regulations. The programme for government outlines the imminent introduction of new national building standards requiring new housing to have a 40 per cent lower heat energy demand than existing building standards and a further revision by 2010 to achieve a 60 per cent reduction.

This mirrors developments in the Dublin area led by Fingal and Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown local authorities but as Minister for the Environment Gormley is keen that local authorities continue to improve the standards they set locally: "I'd say keep going, push the boat out – you have support here in the Customs House.

"I know time is of the essence. The 40 per cent has to ready before Christmas – these are ambitious targets. What I would say to people is this: if you have good ideas, and so many people do, we're going to be receptive to those. Be creative and be ambitious and you'll find a ready ear here."

Asked if further restrictions on builders demanding more ecologically sound and energy efficient buildings would contribute negatively to an already slowing market, Gormley argues that this is not the case: "First of all, I don't see it as an unnecessary impediment. In fact, I see it, as we enter further into the twenty-first century, as a necessity. They shouldn't see it those terms, they should see it, to use a phrase from the Stern report, we talk in Europe about burden sharing in relation to climate change but the Stern report talks about opportunity. Don't see this as an impediment, see this as an opportunity and, in a competitive market, those people that are ahead of the posse will do well. There are developers out there, believe you me, who believe that they have been held back by the inability of previous governments to see ahead. They now, [due to] the fact that we're in here, feel that they've been unleashed. It's up to people then to look at that and see it as an opportunity – and it is.

"I think that over the next number of years we'll be getting developments which are sustainable and I'm not just talking about insulation, I'm talking about all of the issues: are they family friendly, are there families moving in, do we have facilities there for those families? That's what real sustainability is about. I see it as an exciting prospect."

Minister Ryan

Energy for the future

Entering the cabinet alongside Gormley is his party colleague Eamon Ryan. As much as Gormley is known as the impassioned campaigner, Ryan is considered an ideas man, a policy wonk who's not afraid to get to grips with the devilish details of legislation. As Minister for Communications, Energy and Natural Resources he will have plenty of opportunity to both formulate broad policy ideas and wrestle with the details of their implementation.

Just in the door, Ryan is already faced with a range of issues that he wants to address: "There's a whole range of different priorities," he says.

Among these Ryan placed one energy issue as front and centre of his responsibilities and goals: "A three percent [emission] reduction per annum is the target, is the measure – it's simple but [will prove] hugely difficult. If you look at the fact that our energy use is increasing three per cent per annum at the moment, to get an emissions reduction of three per cent per annum – a direct reversal of where it's going – is not insignificant, but that target for me is

the best, simplest, most concrete goal.

"It has two obvious sides: one is that it mirrors closely the projected decrease in the availability of oil following a peak in oil production and therefore it's inevitable, and in terms of global oil supply for what is two-thirds of our energy component, and [secondly] in terms of climate change it allows us to meet the international targets we're already committed to in the European Union to achieve something like a twenty per cent reduction on 1990 levels by 2020."

According to Ryan no one sector should be able to shirk its responsibilities to reduce emissions, otherwise the entire programme will face difficulties: "You have to achieve it everywhere. When you have these demanding targets, no one sector can excuse itself. In other words, you can't have transport saying, 'Ah well, it's all about heating.' The reality is they are demanding targets and it will be difficult and if one sector doesn't do its part it makes it almost impossible in another sector so I think it has to be across the board."

Ryan admits that the pace of change, however, is likely to differ across the sectors: "In terms of emissions, the agriculture area is obviously the most difficult because of the nature of the animal herd issue [but] I think there will be some progress in that as changes in European agriculture occur. The other three main areas, heating, power generation and transport – I would think that probably heating is probably the easiest, first and most cost-efficient means of achieving change. Power generation probably comes next because we have huge opportunity. I think transport is the most difficult one but to my mind it's a more political issue in terms of us looking at and maybe changing investment priorities across the transport area. But again I see it as possible," he says.

Asked if increased taxation on fuel, whether directly on the fuel, or based on some kind of carbon quota system would lead to a rise in fuel poverty, he admitted to the problem but says it can be addressed:

"We do have fuel poverty. We have a lot of people on lower incomes who are spending a large percentage of their budget on imported and very expensive fossil fuels. In terms of a carbon levy, I agree with analysis of John Fitzgerald and Sue Scott of the ESRI [regarding] a carbon tax applied at source, which is cheap and easy to apply, and the revenues from which are used to reduce other taxes and indeed increase social welfare benefits to tackle fuel poverty. [This] addresses the issue of the social disadvantage that such a tax might incur and provides an actual stimulus towards economic growth. I think the analysis that ESRI did on that, in my mind, stands up reasonably well," says Ryan.

"The second issue is houses that are poorly insulated and that's a real issue. That's why one of the things we were glad to see in the programme for government was a commitment to a hundred million Euro spend on grant insulation, specifically aimed at existing primary residences, and in particular at the private sector because a certain amount has [already] been done in the social housing area. We still have tens of thousands of houses that have no insulation, no attic insulation, no wall insulation. That grant insulation scheme when it’s designed could be done in a way which benefits those on lowest incomes the most."

Aside for grant aid Ryan argues for the commodification of retrofitted insulation to ensure ease of installation and thus wide take-up: "One of the things that will have to be achieved is to make it very easy for someone to do the right thing. One of the problems at the moment if you're trying to reduce the emissions or reduce the waste of energy in your house is that it's often a bespoke individual job. You've to learn yourself what sort of technology is appropriate for your house and you have to find out who supplies it.

"In Dublin, for example, all of those 1880s, 1890s red-brick terraced houses have very similar characteristics: the same type of materials, the same type of design and structure. Similarly, [with] most houses built in the 1960s similar technologies apply to the time. I would hope that we can design a grant that provides a standardised response. That has a number = of advantages. Firstly, in the same way one buys a kitchen unit, I think we should similarly have a kind of scheme where you say, 'I want the 1960s 'A' insulation job so that someone comes and does it fairly quickly and fairly cheaply."

Communications minister: Eamon Ryan talking to Construct Ireland editor Jeff Colley

Ryan is also clear that he sees it as the state's responsibility to encourage the further development and use of alternatives to fossil fuels, not to fund them ad infinitum: "In terms of the whole grant area, I don't think we should be looking at grants as the long-term, only way we can deliver particular technologies. I think we recognised with the heating in the Greener Homes scheme that we had technologies that were at a comparative disadvantage because they didn't have the supply chain set up over time.

"We've been using gas and oil-fired burners and boilers and other systems for over 50 to a hundred years. Over that time you set up the distribution system to provide that type of product. We need grant systems to make the alternative distribution and supply chain, for example that you have a chain of wood pellet distribution, that you have a capacity in terms of people putting in solar panels – you use grants to set up that capacity. The state then withdraws, it doesn't see itself as being right in the middle of the whole industry, forever and a day providing grants because the state doesn't necessarily know which are the best technologies and it's very expensive. You want to make it cheaper by setting up a scale of delivery supply systems so that then it becomes the default option."

Beyond simply insulating homes and promoting the use of renewable energy, even the possibility of mandating it with new homes, Ryan is promoting a broad view of domestic energy use: "Obviously airtightness is one way in which you can achieve real gains [but] you want to keep it simple to keep the price down. I'd be slightly wary of making it so comprehensive that you actually might make it very complex. The rough figures pre-1979 for houses with no attic insulation is over 200,000, something of that order. Before we even think about starting to make houses airtight, tackling those 200,000 with effectively no insulation is the first task. You pick the lowest hanging fruit then you start [going] up from there.

"I think what you also need to do is start developing some building expertise and I think what we might see in the regulations on new buildings which set higher standards in terms of energy efficiency, what that might do is give you building expertise in terms of Irish contractors who have knowledge of how to provide airtightness in the new-building sector [and] they then might transfer into other sectors."

The two last years have seen huge steps forward in sustainability with local authorities, such as Fingal, Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown and Wicklow, taking on the responsibility for demanding reductions in energy consumption over and above those set out in building regulations in new buildings as a condition of planning, along with mandatory renewable energy requirements. The new minister is firmly supportive of these kinds of measures: "I'd encourage any local authority or developer who wanted to go beyond national standards to do so. They have to take into account a number of factors. One of the things, I suppose, is just the geographic [and] demographic [specifics] – in something like a city council, where often it's going to be apartment developments, you can deliver certain gains because of the nature, it's much easier than it would be in a one-off housing context. Each different council is going to have to take that into account."

Energy use in the home isn't all about heating, of course, and Ryan is also aiming to see changes in electricity supply: "Over the lifetime of this government I would like to see every single electricity consumer in the country have a smart meter – that's the aspiration. Now, what type of metering has to be decided. My preference would be one that, again, takes a long term view and is as interactive and innovative as possible. That might mean something that can firstly offer you net metering and also then going on to having some sort of control systems where we can start reducing our electricity demand at peak time."

With smart metering, however, comes the potential for a sticky political problem: just how smart will the metering be and will householders be happy to see electricity suppliers monitor and control how, when and on what they use electricity in the home? Ryan dismissed privacy concerns saying that the scheme will work on a cost-incentive basis: cheaper electricity for those who volunteer for such a scheme. He gives the example of customers wanting lower cost electricity being notified by suppliers, for instance, to switch off a freezer for an hour during peak load, an act which should have no impact on its contents, in order to reduce the overall demand.

Another interesting option which may be possible to push through is an idea which Ryan has heard from Toyota: plug-in hybrid cars: "You would plug in the car but only switch it on when there's a very windy night.

"You're, in a sense, using smart metering as a storage system. You're storing electricity in your transport as an energy storage system on a variable basis depending on when power is most cleanly and cheaply available," he says.

A perennial issue when it comes to electricity in Ireland is whether consumers with access to the ability to generate their own electricity from renewable sources will be able to be paid as producers for contributing into the grid – net metering. Unsurprisingly, minister Ryan is in favour or such a development: "I think the details have to be worked out. The government has given a clear signal in the programme for government that we want to encourage the introduction of smart metering and it’s up to the other state agencies, regulatory [bodies], ESB and other people who would be involved in delivering it, to see that clearly as an expression of government intent.

"Again, without working out the details, I would have thought a simple enough system where you can start reversing the meters would provide a very easy to introduce incentive without major contracting and other structures. It exists in the North, it exists in the UK, it exists in other countries around the world so I would hope it can be introduced here."

Moving beyond environmental concerns Ryan sees the possible introduction of net metering as a step toward a major structural change in the country's electricity network: "I think there needs to be a fundamental strategic decision taken in companies like the ESB and elsewhere: are we moving towards a distribution system in terms of a way of meeting this very tight picture that we have? The regulator and the ESB and Eirgrid have a difficult job because there is a security of supply issue. My view is that the government, by signalling we want to move toward net metering, by signalling that we want to move towards a distribution grid, is saying that is one of the main ways we want to achieve energy security."

On the future of Sustainable Energy Ireland, Ryan is clear that the body will continue to develop and implement strategies to help Ireland make better use of its energy: "They have a huge job. They have been working, I think, flat out because they have taken on new responsibilities and they have delivered: the Greener Homes scheme, the main criticism people would have of it is that it has been a runaway success, the numbers have been way beyond what people would expect. Likewise, the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive is a hugely important task and they've taken that on at the same time as running all the other services, research and support schemes.

"I think they themselves, SEI, would recognise that five years on it is healthy to step back and have a look and see 'What exactly is our role?', 'Where are we going?' and I'll have to appoint a new chairman to the board and a number of other board positions which might help with that review process.

"I'd go back to the first fundamental point I made: we have a goal of trying to reduce emissions by three per cent, per annum. That requires every arm of the state to actually be involved, that requires every department, that requires every minister to take it on as their role – this is a whole of government target. What we have in SEI is an independent centre of expertise which can provide advice and clarification to other arms of the state in terms of 'This is the energy related to your area, this is the background understanding to what we actually need to effect change.'"

- Articles

- policy

- Green Power

- Green Party

- emissions

- Minister for Communications

- energy

- natural resources

- environment

- heritage

- Local Government

- eamon ryan

- John Gormley

Related items

-

History repeating

History repeating -

Much ado about nothing

Much ado about nothing -

Ireland joins whole life carbon data initiative

-

WorldGBC launches green building policy principles for governments

-

Decarbonising buildings “most important issue” – Climate Change Committee

Decarbonising buildings “most important issue” – Climate Change Committee -

The world energy crisis 2022

The world energy crisis 2022 -

Techrete aims for net zero carbon by 2030

Techrete aims for net zero carbon by 2030 -

Grant heat pumps at centre of NI energy transition project

Grant heat pumps at centre of NI energy transition project -

#BuildingLife: Addressing the environmental impacts of buildings across their life cycle

#BuildingLife: Addressing the environmental impacts of buildings across their life cycle -

Campaign launched to tackle whole-life environmental impact of buildings

Campaign launched to tackle whole-life environmental impact of buildings -

Programme for government aims for 500,000 retrofits

Programme for government aims for 500,000 retrofits -

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries