- Policy

- Posted

Greening public procurement

Ireland has been waiting for a green procurement plan in the public sector for two years. Jason Walsh looks at what the plan should include and why it is needed, now more than ever, and with sustainable building at its core.

Much has been made of how the recession can be fought by making a real commitment to sustainability – week-in and week-out the media and government talk about so-called 'green collar' jobs, renewable energy and more. So loud has been the talk of the 'green New Deal' that it would be easy to think Ireland was already on its way to economic recovery led by a new dispensation in environmental and energy issues.

Sadly it's not true. There is no conspiracy at work. No-one doubts the government and civil service's commitment to improving the economy and environment in tandem. It just seems that no-one quite knows what to do. Given that the current economic environment is widely touted as the worst recession since the Great Depression, this is hardly surprising.

Ireland needs bold moves and in a time when private sector investment has declined to the point where many businesses are simply hoping to survive until the economy picks up, it is up to the public sector to point to a new way of doing business.

Everyone in the construction industry is well aware of the decline in work, in both residential and commercial projects. At times it feels as if the only work still going on is either one-off houses or in the state sector. Public sector work alone can’t be expected to keep the industry afloat but considering the amount of construction, both new-build and in particular refurbishment that is going on in the state sector, it does provide an opportunity to set the standard for greener construction.

What is green procurement?

There has been some question as to what, exactly, is covered by the term green public procurement. The requirement for an action plan and policy is laid down by the Department of Energy in a document called: "Maximising Ireland’s Energy Efficiency: The National Energy Efficiency Action Plan 2009 – 2020." The procurement policy is set out as the responsibility of the Department of the Environment, which has been charged with having green public procurement guidelines in place before the end of 2009 – a full year later than the date earmarked in the version of the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan sent out to public consultation in October 2007.

The following statement from the green procurement section of the finalised plan gives a sense of the government’s stated ambitions: “The total Government purchasing budget is over e10 billion per annum, giving significant leverage to procurers in the public sector to ‘move the market’ towards the competitive provision of sustainable products and services. To maximise this leverage, while also maximising energy efficiency and associated savings in its own estate, the public sector must take the lead through, inter alia, the procurement of energy-efficient accommodation, mobility, products and services”.

The plan is certainly not short on ambition. “We will publish Green Public Procurement Guidelines that will aim to achieve a level of green public procurement equal to that achieved by best performers in the EU,” it states. “The Guidelines will underline how high environmental and energy efficiency standards must be an integral element of value for money across the whole range of public purchasing”.

Riona Ní Fhlanghaile, who heads up the Department of the Environment's Environmental International and Sustainable Development section, and is responsible for green procurement, told Construct Ireland that green public procurement covers construction work: "Public procurement is everything that the public sector buys," she said.

"It's a huge area, right down to the cleaning products used in buildings."

Construct Ireland editor Jeff Colley had previously contacted Ní Fhlanghaile in January and was given a quite different answer – that the department was working on green public procurement guidelines, but that construction was not included.

According to Ní Fhlanghaile the Department of the Environment has yet to produce the procurement policy, but she points out that this doesn't mean that green procurement, and indeed construction, isn't going on: "There is stuff happening in the OPW (Office of Public Works) and local authority housing. Some of the new-builds under the decentralisation programme would have sustainability requirements [for example].

"There is a lot happening," she said, "the absence of the green public procurement action plan doesn't mean things aren't happening. It's more important that it's done than it's written about. There's always more to be done. "There is an absolute commitment to green public procurement," she said.

Ardee local area offices

Construct Ireland takes a supportive but critical view of the issue – 'on side' but not necessarily 'on message'. In discussions with industry figures, experts and public servants, Construct Ireland has come to the conclusion that while much laudable work is being done in particular pockets of the public sector – some OPW & Department of Education projects stand out for instance, along with the occasional social housing scheme. However, this is no substitute for a centralised policy, applied across all state and semi-state bodies.

The problem with the current situation is that without a dedicated and universal action plan the need for sustainability may be ignored. There is a very real danger that sustainability will only be a factor when happenstance means that knowledgeable and committed architects, engineers, consultants and public servants happen to be working on a particular problem.

One very recent significant example does not inspire confidence. Construct Ireland has become aware of a Health Service Executive (HSE) tender document for the supply of heating, cooling and lighting of all HSE buildings over the next 15 years, where no reference to sustainability requirements is mentioned whatsoever, with the exception of one reference to the use of energy efficient technology. This is shocking given the size of the tender – the HSE estimates that it relates to “in the region of 3,500 buildings”.

The tender includes no reference to the use of renewable energy, to a desired reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, or to improving energy performance of the envelope of HSE buildings. There is no acknowledgement of the need to ensure that energy saving strategies improve rather than compromise occupant health and comfort. This issue in particular should be of particular concern to the HSE, given the impact that a healthy indoor environment (with good ventilation levels, and a consistent room temperature) can have on occupant health, and, it follows in many cases, patient recovery time. Indeed, much of Ireland's stock of health sector buildings are pre building regulations, lacking even the most rudimentary wall insulation, and equipped with antiquated single-glazing. In some cases ventilation is only supplied by the manual opening of windows - a shocking situation, in light of the high risk of infection between patients.

Similarly, in this day and age, 2009, with attempts to reduce the acceleration of climate change central to government policy, it is very curious that no reference to carbon dioxide emissions reductions is included in this tender. And it does not necessarily follow that delivered energy savings result in carbon savings.

In spite of repeated attempts, we have been unable to obtain comment from the HSE on the issue and are particularly concerned that with buildings whose entire purpose is to make people healthier, failure to recognise the importance of sustainability and its impact on health will result in longer hospital stays and, therefore, a further drain on public finances. In instances such as this the pressure on public finances cannot be used as an excuse to lower building standards – the long term cost is simply too high in both ethical and financial terms. A cost-benefit analysis must be put in place.

A Department of Education schools programme

One senior public servant who spoke to Construct Ireland echoed Riona Ní Fhlanghaile's feelings: "If you go to the procurement divisions of the prison services, health, defence [and so on] there are excellent people there. There is excellent stuff happening."

However, the same public servant expressed some reservations about the lack of an action plan, arguing that its implementation would result in joined-up government, exactly what is needed on the issues of both sustainability and government spending.

Peter Seymour of Ecocem argues that the action plan should strongly support materials with superior performance and lowered embodied energy and pollution.

"Ireland lags behind every other EU country on green procurement," he said. "We're well behind."

Of course, Seymour has a product to sell and openly admits this. Ecocem sells ground granulated blastfurnace slag (GGBS), an alternative to Portland cement which makes use of by-products of the steel smelting process. The key benefit of GGBS is that is has substantially lower embodied energy and carbon than traditional cement products. Using as much GGBS as possible in projects where concrete is required makes sense from an environmental point of view and mandating this in a document covering all government procurement would be a simple act.

It may be perceived as a problem that Ecocem is the only company that sells GGBS in Ireland; that the government cannot dictate that all cement products must come from a single supplier. As Riona Ní Fhlanghaile explains, it’s not an issue: "I don't think it would be a problem,” she said. “Ecocem may be the only supplier in Ireland but they're not the only supplier in Europe; there are other companies who supply [GGBS]."

Beyond ensuring that the green public procurement action plan is more than just a toothless document that says government offices should use recycled paper it is essential that procurement in relation to construction and infrastructure projects must be detailed and take into account all ways of reducing environmental impacts from the embodied energy, toxicity and end-of-life value of the materials right up to how the building performs.

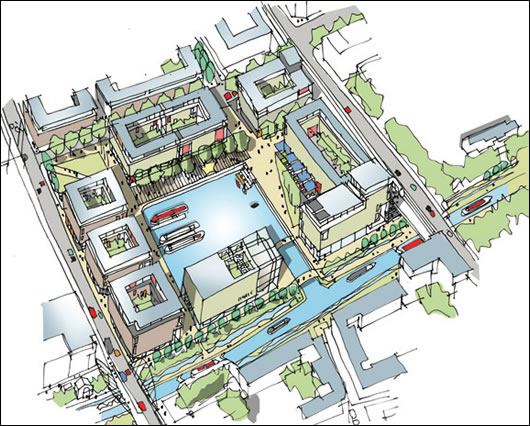

There is no doubt that these issues can be tackled. The example of the Clonburris Strategic Development Zone, where design policy and specification was mapped-out in real detail shows this, including ambitious green requirements for construction materials, for the energy performance of the buildings, and for the overall environmental impact of the new development. In addition, any reluctance on the part of the construction industry to alter its methods and materials has faded away – the need for work at any cost is too high for the industry to haggle over particulars.

This argument is not intended as an attack on the public sector. Much good work is going on at many levels, Construct Ireland is merely arguing for the action plan to be fast-tracked. It is clear the government is willing to set the standard in sustainable construction – we simply want to see this done across all areas of state spending as soon as possible.

As Peter Seymour says: "A group is being put together by the government purchasing unit and OPW. They report to the public purchasing unit within the Department of Finance. Eamon Ryan made an announcement on energy initiatives [and] buried within that was a reference to work starting on green procurement.

A bird’s eye view illustration of the canal basin at Clonburris, a proposed development which is infused with world-class sustainability

credentials

"They have two objectives. Firstly, to set general guidelines for green purchasing. The other is to set specifics such as motor fuel and so on and set targets within that."

There is, however, the issue of technical proficiency. The Department of the Environment provides long-term and wide-scale guidance to the public sector but the nitty-gritty of technical decisions still need to be made. This is of particular concern with local authorities which show significant variation from county to county in their commitment to green issues. Construct Ireland has heard of several cases, including once this year, where local authorities have excluded timber frame companies from involvement in social housing tenders, instead insisting on the use of cavity wall construction.

The OPW has already introduced a green audit for its own work, surely a sign that the expertise located within its offices could be shared with other relevant bodies engaged in construction procurement? This help could be offered on an informal or formal secondment basis depending on the complexity of the project and questions involved.

Certainly, given the OPW's track-record on green issues, there should be no resistance to working with other parts of government to share the applicable experience it has built up over the years. In this case, wider consultation need not mean putting work on the long finger – in fact, it could result in a green public procurement policy being developed and published as quickly as possible.

Greening Ireland

Construct Ireland has never been afraid to put its neck on the line and it is in this spirit that the magazine presents its suggestions on the issue of green public procurement. Consider this simple, eight point plan, a manifesto for a green public service.

1. Public procurement policy must be green and must include construction

Understandably many green procurement practices are focused on office equipment and supplies. These are often the most visible areas in which any office can improve its green credentials. Construct Ireland holds no brief against recycled paper or low energy computers but the reality is that measures of this kind are = not enough. Individual offices and office managers may wish to make a contribution and any such moves are welcome but when it comes to creating an effective policy that operates right across the public sector it is imperative that building design, construction and refurbishment are at the top of the list.

Ireland has little in the way of heavy industry. As a result, some of Ireland's most significant energy and pollution issues are in the areas of agriculture and the construction and operation of buildings. While it is true that construction has been devastated by the recession it has not ground to a halt altogether and may resume significant activity in the coming years. Without policies in place now, the construction industry will find it too easy to resume 'business as usual'. While any regular reader of Construct Ireland can see that Irish building has improved beyond recognition in the last five years in terms of basic energy efficiency, the country still has a long way to go.

Moreover, even with the recession, public building continues: schools, hospitals and local authority housing are all examples of construction work that simply must continue. Given that Ireland's obligations as a member of the European Union include carbon emission penalties it is imperative that any new buildings are designed and built with sustainability in mind.

In addition, in line with stated government policy to improve energy efficiency across the public sector many ageing public buildings will need to be significantly upgraded and improved. While it is tempting to make large and visible public statements with green technologies like wind turbines and solar panels, the reality is that the first step must be to consider the energy performance of existing buildings.

Energy minister Eamon Ryan TD at the launch on the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan in May. The plan includes commitments to have green procurement guidelines in place this year

2. Any procurement policy must consider the issue of embodied energy in materials

As energy demand decreases through better thermal performance standards, embodied energy in materials becomes a greater percentage of a building's total energy use. It therefore makes sense to choose materials with lower embodied energy. Natural materials which require less processing should be used wherever possible.

3. Any procurement policy must consider the issue of embodied carbon

As with the issue of embodied energy there is also the issue of embodied carbon. With carbon emissions now being capped at EU level it makes sense to consider the issue separately from overall energy use. Low carbon materials will not only help Ireland meet its EU targets but will also make an important statement in terms of moving toward zero carbon buildings.

4. Materials should be chosen with a view to their full life cycle

Re-use, salvage and recyclability all need to be taken into account with building projects. A building's life-cycle should understood in terms of the useable life of all of its materials and not merely the length of occupancy.

Re-use is preferable to recycling as it has lower energy requirements. Some building such as the Emerald Housing Scheme in Ballymun are making use of materials salvaged from the demolished housing stock. If re-use was factored in at the design stage this process could go a lot further. A good example of this is using mechanical fixings for timber joints rather than glues. This allows a building to be easily deconstructed at the end of its life.

The public sector should also factor in the cost of disposal of materials, especially of toxic, hazardous and unsalvageable materials – a capital loss – set against the value of salvaged material, a capital gain.

5. Where applicable, energy performance should be addressed first through the issue of the building envelope

As always, it is essential that energy efficiency be considered before energy generation. This is of particular concern with older buildings that need refurbishment as without a commitment to correcting the building envelope with air-tightness, good insulation and designed ventilation, any benefits of renewable energy will be lost. In the health sector this is particularly pressing – it is not possible to simply lower the thermostat by a degree or two to make savings.

6. At this point renewable energy should come into the picture

Renewable energy such as solar thermal and on-site microgeneration of electricity have a significant role to play in the improvement of Ireland's public buildings. Once the building envelope has been designed properly use of renewables can lead to huge savings in terms of not only costs, but also carbon emissions. In addition, Ireland has a nascent renewable energy sector and supporting it means supporting jobs, surely a key factor during a recession.

GGBS was used extensively in the concrete at Father Collins Park

7. Cost benefit analysis should be used to assess the real price of procurement

A rigorous cost benefit analysis tool should be applied to all public procurement, wherever practicable. At the most obvious level, this would enable the state to correlate the capital costs of a building to the estimated running costs, and adjust accordingly. This should also take into account a cost for procuring carbon permits, both in terms of carbon embodied in the building and emitted throughout its operational life, and the value that can be realized from specifying salvageable materials, which can be sold when the building reaches its end of life, as well as the cost of disposing materials that can’t be reused or recycled.

A cost benefit analysis tool developed by Peter Clinchi, now a senior policy adviser to Brian Cowen, attempted to quantify the benefits of energy efficiency measures in buildings in terms of health, comfort, and environmental gains. Clinch therefore showed the indirect economic benefits, including reduced health care costs to the state resulting from sicknesses caused by living in cold, damp buildings. A broad version of this type of cost benefit analysis should be applied whenever the public sector is deciding to procure or refurbish a building, whether it be an individual dwelling, a civic office, or a hospital.

8. Co-operation is essential

It's all too easy to lay the blame for lack of progress on one or other state agencies or bodies but the truth is that small countries like Ireland are well placed to get work done quickly. Any relative lack of expertise can be worked around by having co-operation between public bodies such as the Departments of Energy, Environment, Education &Finance with the Office of Public Works, HSE, local authorities and their energy agencies, Sustainable Energy Ireland and the private sector. The need to stimulate the shift to a green economy is too urgent to allow it to become a territorial issue.

The private sector could play a key role by facilitating greater capital investment in green procurement on the basis of reduced running costs and creation of new income streams, ranging from selling energy into the grid or into adjacent buildings, to capitalizing on the salvage value of building materials. This could involve a version of the ESCo, or energy service company, that also takes into account broader environmental gains such as reduced spend on water and waste disposal.

i Cost-benefit analysis of domestic energy efficiency, Clinch, J. Peter & Healy, John D., 2001

- Articles

- policy

- Greening public procurement

- Department of Energy

- Clonburris Strategic Development Zone

Related items

-

Ireland joins whole life carbon data initiative

-

WorldGBC launches green building policy principles for governments

-

Cuckoos & magpies: state house-buying hits record

Cuckoos & magpies: state house-buying hits record -

Blind & shutter group calls for Part B changes

Blind & shutter group calls for Part B changes -

Wales votes to cut emissions 80%

Wales votes to cut emissions 80% -

Filling the retrofit policy void

Filling the retrofit policy void -

Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink

Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink -

Policy for zero, or zero policy?

Policy for zero, or zero policy? -

Why construction contracts must change in light of Grenfell

Why construction contracts must change in light of Grenfell -

Government ‘Help to hoard' scheme - why we’re not building homes

Government ‘Help to hoard' scheme - why we’re not building homes -

Grenfell Tower - How did it happen?

Grenfell Tower - How did it happen? -

Out of control? Are building control systems properly equipped to deliver safe, healthy and well-constructed buildings?

Out of control? Are building control systems properly equipped to deliver safe, healthy and well-constructed buildings?