- Renewable Energy

- Posted

Renewable Energy Grants

As oil prices surge and the need to rapidly switch to energy sources that are secure and environmentally friendly becomes increasingly apparent, more and more Irish people are tapping into the renewable energy resources at their disposal. But are the Government giving people the incentive to make the switch? John Hearne investigates.

“Every second customer who rings us asks what is the status regarding incentives. We have to tell them: Fine words of encouragement and that’s it.” Paul Sikora of geothermal heatpump company Dunstar expresses the frustration of an entire industry.

If you go to the effort and expense of incorporating renewable technologies in building your home, if you install a heatpump, a wind turbine, a solar panel, photovoltaics, or a pellet stove, the Government will offer nothing to defray the costs. This is despite the fact that support schemes are in place throughout the EU, despite the fact that an independent report commissioned by the state agency, Sustainable Energy Ireland (SEI) concluded that some renewable sectors will never progress beyond infancy without support, despite the fact that a recent report by Dr. Peter Bacon estimated that Ireland is facing EU fines of up to €4 billion should it fail to meet its Kyoto obligations, and despite the fact that the economy is dangerously over-reliant on non-renewable energy sources. “At the moment,” Sikora continues, “geothermal in practice is limited to people with fairly generous budgets building near the upper end of the prestige housing market. Anybody that is having trouble putting funds for a mortgage together finds, whether it be panels or geothermal or even something like a condensing boiler, the expense is off-putting…People very often say, not this time. In practice, people don’t set about building their own house too many times in a lifetime…”

Two years ago, SEI commissioned a report from the Danish Energy Authority (DEA) on active solar thermal energy in Ireland . Among its conclusions, the report states that “no successful solar thermal energy development in Europe has taken place without some sort of public support, and the same conclusion will probably be true for Ireland .” While the report dealt exclusively with solar thermal technologies, co-author Jens Windeleff says this conclusion can be applied across other renewable energy technologies such as wind turbines, geothermal heat pumps or pellet stoves and boilers. “If you want a significant development, the European experience shows very clearly that it would not be possible without some grants or national funding or tax reduction or whatever. That’s the lesson learned from twenty years of European development.” He’s keen to emphasise that these supports need not, indeed should not prop the sustainable sector in perpetuity. In Denmark , a domestic subsidy for both wind turbines and solar thermal heating began at 30% and as the sector strengthened, that subsidy was gradually reduced to zero. Both sectors now thrive in an unsupported, free market. “You see the same thing in Japan .” Windeleff continues. “They had a very strong subsidy for solar electricity for many years and they are going to cancel it next year totally because it’s not necessary any more.” The DEA’s report included a study which found that the financial costs of a support programme for solar thermal heating balanced with the savings it would deliver. “The purpose was not to make a detailed economic calculation but just to tell programme managers and politicians that you don’t have to fear that this will lose money…You will make a lot of meaningful new jobs and it would help fulfil the Kyoto obligations, so if it’s financially useful why don’t we do it?”

Why don’t we do it? To answer this question, you’ve first got to look at SEI’s House of Tomorrow programme. This is a National Development Plan (NDP) funded scheme administered by SEI which delivers grant aid to developers who incorporate sustainable technologies in residential construction. Grants of up to €8,000 per unit are available ‘ contingent on a bottom line aggregate improvement in energy and CO2 performance.’ In effect, each housing unit has to exceed building regulations by 40% or more in order to qualify for the maximum grant. The catch is you’ve got to build twenty units plus to qualify.

Though it has its critics, House of Tomorrow is now hailed a good programme by many. It aims to reward innovation, boost standards and ultimately can deliver housing units which incorporate a strong renewable dimension. Thus far, the programme has supported 39 housing developments comprising over 1,800 units all over the country. Wexford County Council is currently constructing 27 houses in Oylegate which use solar water heating and wood pellet stoves. Another House of Tomorrow supported development in Cavan incorporates solar water and air heating together with a heat recovery ventilation system.

The problem is that it’s a case of either or. We get a developer’s grant or we get a single build grant. Right now, policy favours developers. Why have we moved in this direction when the DEA report concluded otherwise? Kevin O’Rourke of SEI protests that the report’s conclusions were taken on board. He states that there were however a whole stack of unrelated reasons for going with House of Tomorrow. Some are apparently intensely bureaucratic. In 1999, the Government published its Green Paper on Sustainable Energy. In dealing with the built environment, it proposed Government intervention in the areas of demonstration and development. According to O’Rourke this policy aspiration subsequently became action and found its funding under the NDP. Because the intervention was originally slated for research and demonstration, we got House of Tomorrow and not a single technology grant. “Secondly,” says O’Rourke, “We’re trying to bring about systemic change within the construction industry supply chain by means of intervention to address the gaps that the analysis of the Green Paper and indeed consultation with the industry at the time would have highlighted.” A further reason cites the fact that House of Tomorrow supports ‘whole-house’ solutions rather than individual technology solutions.

There is also a suite of arguments against grant schemes generally; that they raise prices, that the benefit is diverted to the contractor, that they engender a cowboy factor. “That’s an argument against any and all grants.” Says Paul Sikora. Moreover, he points out, support does not necessarily mean direct grant aid. He suggests a VAT reduction or a tax credit. “Tax breaks are handed out left right and centre when the Government wants to incentivise something, whether it’s building prisons, nursing homes or flats. There’s an argument that those grants wind up in the developer’s pocket and no one seems to be bothered about that…It’s an easy dodge for officialdom to just say we wouldn’t want to be enriching some of these renewable contractors. They’ve enriched lots of other people and they don’t seem to be kept up at night.”

Peter Keavney at the Galway Energy Agency believes a VAT reduction is the way to go. “It only takes a small intervention to actually get an indirect grant aid or support, and I think that it should come though the VAT route. We’re not asking to get rid of VAT altogether, we’re saying to take 20% of it off and leave it at 1% so it can be adjusted again accordingly.”

As to whether or not a support scheme would draw cowboys into the industry, critics of the current regime point to the success of the Clear Skies programme in the UK . This is a single technology grant scheme where individual householders can claim anything between STG£400 and STG£5,000 for using renewables in their build. The scheme incorporates an accreditation programme to ensure grants are only paid following the correct installation of quality equipment. “I don’t see that the bureaucracy behind it is insuperable at all,” says Paul Sikora whose company is accredited under the programme and who is installing an increasing number of heatpumps in the UK . Arguably, the lack of accreditation in this country allows cowboys to thrive. “We’ve had to redo geothermal installations for people that have just had disastrous experiences, and that doesn’t help us. We don’t make any money on it and you’re just trying to reduce the bad smell rather than advance the cause.”

So to the future. Kevin O’Rourke at SEI concludes his enumeration of the many reasons why House of Tomorrow prevailed over a single grant scheme by pointing out that this was the rationale that was current five years ago. “All of these things are not a recipe for paralysis. This is an issue that is under consideration”, he stresses. He points however to two recent developments which suggest that policy is unlikely to change. The abolition of the first time buyer’s grant confirms a poor disposition to grants in general, while the arguments against one-off housing don’t particularly assist the single technology grant cause. The Clear Skies programme is funded by the UK ’s climate change levy – effectively a carbon tax. Thanks to the recent u-turn, we have no similar revenue stream to ringfence. That said, it seems clear that the UK ’s experience of single technology grant schemes will have a significant influence on the future direction of policy here. So is it unlikely that we’ll see anything like Clear Skies in the coming year? “It wouldn’t be right for me to comment on that”, says Kevin O’Rourke. “I’d have to say that I wouldn’t want to raise hopes but I wouldn’t put it as negatively as that. It would be imprudent of me to raise anybody’s hopes because there’s many a slip…The Clear Skies programme…if that’s an effective programme, obviously it could be expected to have an influence on policy makers here.” Not the most unambiguous conclusion in the world, but it’s not without hope.

- renewable energy

- funding

- irish government

- photovoltaics

- solar panel

- thermal energy

- clear skies

- Oil prices

- grants

- energy agency

Related items

-

New scheme offers up to €75,000 retrofit loans at low cost

-

Government supported almost 27,200 home energy upgrades through SEAI in 2022

-

Solar panels to receive VAT drop in aim to boost uptake

Solar panels to receive VAT drop in aim to boost uptake -

The 1980s: A renewable revolution undermined

The 1980s: A renewable revolution undermined -

Huge demand for new deep retrofit grants

-

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced -

SuperHomes to ramp up retrofit with new EU funding

SuperHomes to ramp up retrofit with new EU funding -

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

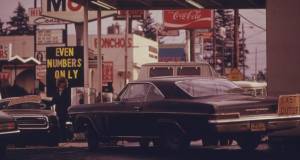

The first oil crisis

The first oil crisis -

SuperHomes Ireland seeks deep retrofit grant applicants

SuperHomes Ireland seeks deep retrofit grant applicants -

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March -

The West Midlands eco house with no energy bills

The West Midlands eco house with no energy bills