- Insight

- Posted

Passive house or equivalent - The meaning behind a ground-breaking policy

Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown’s passive house policy also leaves the door open for alternative approaches, provided their equivalence can be demonstrated. But what does this mean?

This article was originally published in issue 15 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

On 17 February Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council – one of the four local authorities in the Dublin region – voted to adopt its new county development plan, including an historic commitment on low energy building. The councillors passed a motion that I had the honour of wording which means that all new buildings in the county – not only all new dwellings, but all new buildings in general – must be built to the passive house standard or demonstrably equivalent performance levels. The implications of this are profound.

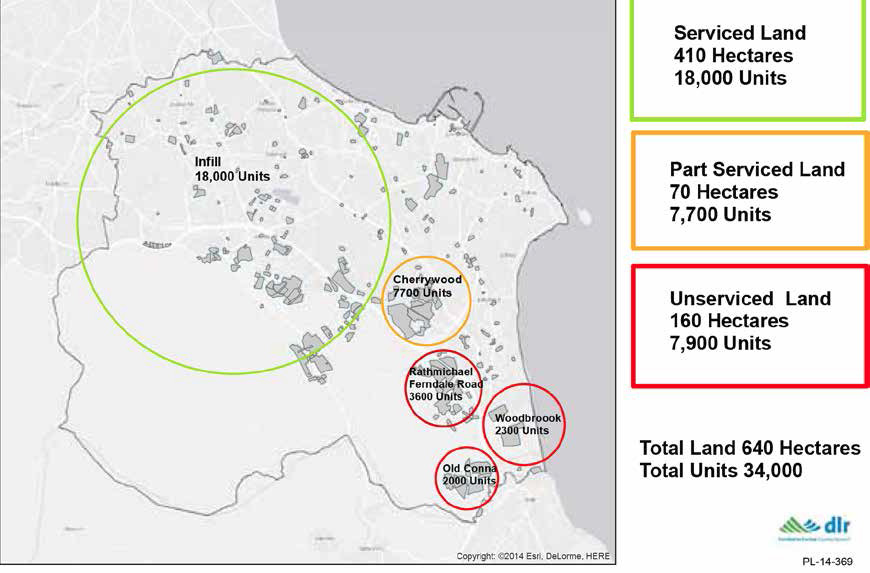

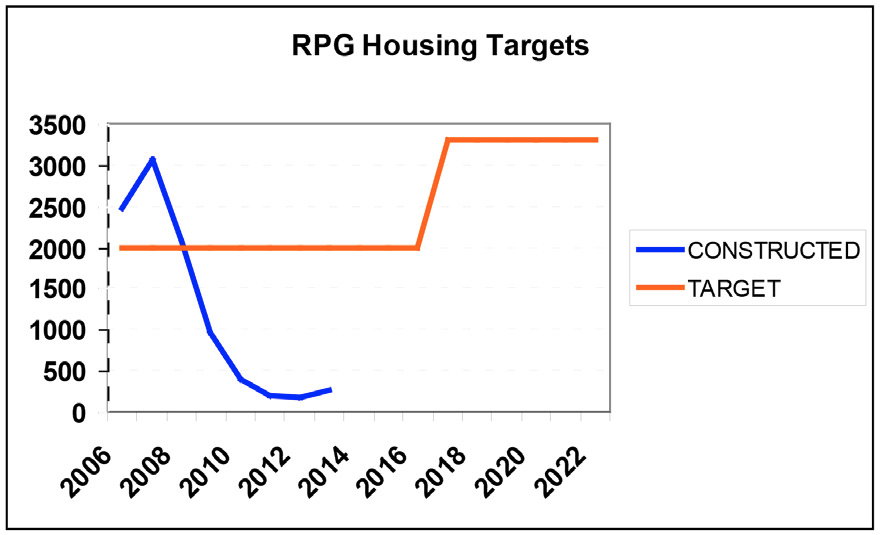

Consider for a moment how many buildings this policy will effect. The development plan take its lead from the Regional Planning Guidelines for the Greater Dublin Area (2010-2022), which set housing allocations for the region. The plan signals an allocation of 30,885 dwellings to be built from 2014 to 2022 – a rate of 3,800 units per year. Remarkably little was built in 2014 and 2015 as the construction industry – and property developers in particular – struggled to keep pace with a recovering economy.

Nonetheless, such is the growing recognition and political consensus of the need to build our way out of an escalating housing crisis, we should expect to see a significant growth in construction output. The council is certainly planning with that in mind, and has calculated the number of new homes that could be built on either serviced or unserviced land within the lifespan of the plan.

Extracts from Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown’s new county development plan give a sense of the quantity of housing that the council aims to see being built within the lifespan of the plan, and a sobering reminder of how low construction output has been in the area in the long hangover after the property crash

One area, Cherrywood, is a strategic development zone, which makes it legally discrete from the provisions of the development plan, meaning its allocation of up to 7,700 homes won’t be subject to the development plan’s requirements. That said, its developers, Hines, would be wise to consider applying the passive house standard, or a genuinely equivalent alternative throughout the new development. Several articles published in Passive House Plus over the years – including the Michael Bennett & Sons scheme featured in this issue – have demonstrated that passive houses can be built for little or no increase in construction costs. That being the case, why would any developer build to a lower standard than neighbouring developments? Leaving Cherrywood aside, it seems reasonable to estimate that this policy could apply to the construction of upwards of 20,000 new homes, as well as a proportionate number of new non-residential buildings. No target amount for non-residential buildings is specified in the plan, but it can be safely read to be in the hundreds of thousands of square metres worth of space.

Let’s start with the wording itself. The wording I prepared – and seeing it in print in the published county development plan is still a shock – is as follows:

All new buildings will be required to meet the passive house standard or equivalent, where reasonably practicable. By equivalent we mean approaches supported by robust evidence (such as monitoring studies) to demonstrate their efficacy, with particular regard to indoor air quality, energy performance, comfort, and the prevention of surface/interstitial condensation. Buildings specifically exempted from BER ratings as set out in S.I. No. 666 of 2006 are also exempted from the requirements of Policy CC7. These requirements are in addition to the statutory requirement to comply fully with Parts A-M of Building Regulations..

But what does this mean? While I worded the policy, it will ultimately fall upon the planners to interpret its meaning, and apply it with regard to planning applicants. So it’s important to bear in mind that what follows is my interpretation of a policy whose meaning is in my view, unambiguous.

The “reasonably practicable” clause has already generated a fair amount of discussion, but it’s uncontroversial. It’s actually taken from Part L of the building regulations – specifically Part L1, the regulation’s main requirement, which states thus: “A building shall be designed and constructed so as to ensure that the energy performance of the building is such as to limit the amount of energy required for the operation of the building and the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with this energy use insofar as is reasonably practicable.” The phrase is also in widespread in local authority planning requirements with regard to drainage and preventing flooding risk.

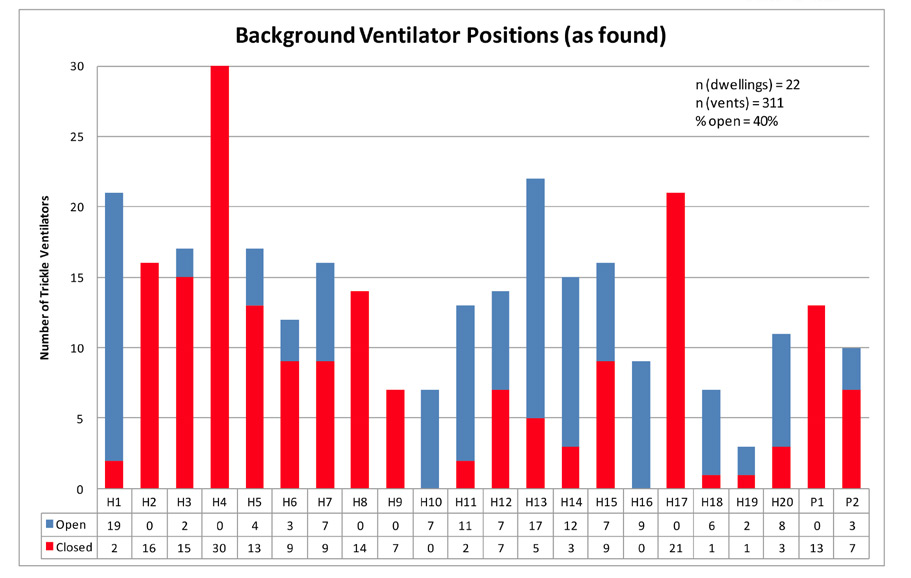

(Top) A UK monitoring study on typical natural ventilation “systems” in 22 homes found that occupants had blocked 60% of vents, (bottom) the 2005 Energy Performance Survey of Irish Housing contained alarming evidence of growing disparity between theoretical and actual energy use in newer homes

While the plan refers to the passive house standard or equivalent, it then goes on to define that equivalence must be demonstrated not only in terms of energy performance, but indoor air quality, comfort and condensation risk. It explains how this equivalence is to be demonstrated, by demanding that approaches other than passive house be “supported by robust evidence (such as monitoring studies) to demonstrate their efficacy.” The reference to monitoring studies is very deliberate. Theoretical figures in guidance documents, codes of practice and software applications are worse than useless if they haven’t been calibrated against the real buildings to which they’re intended to apply. That’s not to doubt the critical important of theoretical tools. It’s rather to say theory needs to be demonstrated in studies of real buildings, with an ongoing feedback process so that information gleaned from monitoring studies informs the theory, and so on.

I mentioned indoor air quality first in the wording, before energy performance, for a reason: it has been neglected for far too long across the industry, and across society. Many people don’t see the sense in insulating a building, only to deliberately replace the air you’ve worked hard to make warm with cold air. And as a University of Exeter study on several hundred dwellings found , homes with higher Energy Performance Certificate scores were associated with statistically significant increases in doctor-diagnosed asthma cases. The highest rated homes in that study had a B rating on the UK’s scale.

Data from SEAI’s National BER Research Tool – a creditable example of open government, a database filled with every published Building Energy Rating for Irish dwellings – shows that the average new home in Ireland built since the current energy performance standards kicked in is hitting a mid-A3 Building Energy Rating, and a calculated score of 60 kWh/m2/yr. Most worryingly, 66% of these new homes are reliant on natural ventilation – either holes drilled in walls or trickle vents in window frames, plus intermittent fans in bathrooms and kitchens.

The consensus across the industry is that such an approach doesn’t work, and that this is bound to lead to significant problems in low energy buildings. These naturally ventilated homes are hitting an average airtightness of 4.08 m3/mhr/ m2 at 50 Pa. Part F of the building regulations, which addresses ventilation, attempts a solution of sorts: a requirement that in buildings with an air permeability of 5m3/hr/m2 at 50 Pa or lower, the equivalent area of vents must be increased by 40%. Not only is there no apparent evidential basis for the efficacy of this general approach to ventilation, a monitoring study for the UK government on typical natural ventilation “systems” in 22 homes found that occupants had actually blocked 60% of vents - a perhaps unsurprising consequence of providing people with ventilation systems that – during the times when they actually ventilate – introduce cold air and create discomfort. And anecdotal feedback from major players in the Irish insulation and ventilation sectors has been that the Part F requirement to add 40% more holes is being routinely ignored in the overwhelming majority of cases.

Unless supported by robust evidence such as monitoring studies to prove equivalence to passive house in terms of energy, indoor air quality, comfort and condensation, the government’s mooted nearly zero energy building (NZEB) definition will fail this equivalence test. All EU member states must produce such a definition and apply it for all new buildings by 2021 thanks to a requirement of the recast EU Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings. This is not to entertain the nightmarish fiction that Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown will be annexed by a post-Brexit UK, and therefore can set its own building standards while ignoring EU diktat. New buildings built in Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown will of course have to satisfy the national NZEB requirement. But unless the NZEB definition and other relevant parts of building regulations are tightened up to pass the equivalence test, it will be the case that only certain approaches to NZEB may pass muster. For instance, take indoor air quality again. While robust evidence – including monitoring studies – does exist to demonstrate that forms of mechanical ventilation other than MVHR can be effective in dwellings, the same cannot be said of typical natural ventilation.

Similarly, there appears to be a paucity of credible data to support the claim of passive stack ventilation, without mechanical back up to kick-in when necessary. In certain weather conditions – such as still, warm days, where there’s neither the wind nor the temperature difference to create the buoyancy to drive the stack effect – it simply won’t work.

Comfort is another area where where other approaches, such as current Part L or NZEB may struggle to demonstrate equivalence. By comfort we mean thermal comfort specifically, taking account of minimum and maximum temperatures. As passive house certifier Tomas O’Leary has argued in these pages before, the temperature assumptions in Ireland’s national calculation methodology, Deap – 21C in living areas and 18C in all other areas – translates in a typical semi-D, where the living area fraction is circa 15%, to about 18.5C for the whole house. That compares to a whole house temperature of 20C in the Passive House Planning Package. And that’s not all: Deap is assuming that semi-D is heated to 18.5C during the heating season, but only for eight hours a day – raising the question: how low might the temperatures drop during the unheated 16 hours. The 20C temperature in PHPP is 24 hours a day. In terms of minimum temperatures, it’s plainly obvious that Deap will assume a less comfortable building than PHPP.

But comfort also takes into account maximum temperatures. Overheating can be a significant risk in low energy buildings – a risk that may increase substantially during the lifetime of new buildings, due to the impacts of climate change – and this is especially so if it’s not considered as part of the design process. Overheating isn’t referenced in the guidance associated with Part L requirements for dwellings, in spite of how far the energy performance requirements have progressed. However it does feature in the 2008 technical guidance document L for buildings other than dwellings, albeit specifically with regard to passive solar gains, as per the following extract:

Buildings should be designed and constructed so that: (a) those occupied spaces that rely on natural ventilation do not risk unacceptable levels of thermal discomfort due to overheating caused by solar gain, and (b) those spaces that incorporate mechanical ventilation or cooling do not require excessive plant capacity to maintain the desired space conditions

Note the reference to naturally ventilated buildings suffering overheating risk by solar gains. How many of the 66% of naturally ventilated new homes in Ireland – which are highly insulated, moderately airtight buildings that should be relatively slow to lose heat – also include substantial south facing glazing? The reality is that the overheating risk in low energy buildings is not merely due to solar gains. It’s also about internal gains from appliances, occupants and building services. The passive house sets a target that maximum calculated temperatures must not exceed 25C for more than 10% of the year, though many passive house designers aim for as little as zero percent.

Energy performance

Unfortunately we don’t know how homes or non-residential buildings built to Part L are actually performing, because the requisite monitoring studies haven’t been done. In fact the only such study to check the actual energy performance of a representative sample of the Irish housing stock – the 2005 Energy Performance Survey of Irish Housing, which remains unpublished, but which SEAI agreed to release to me in 2011 – included an alarming finding in this regard.

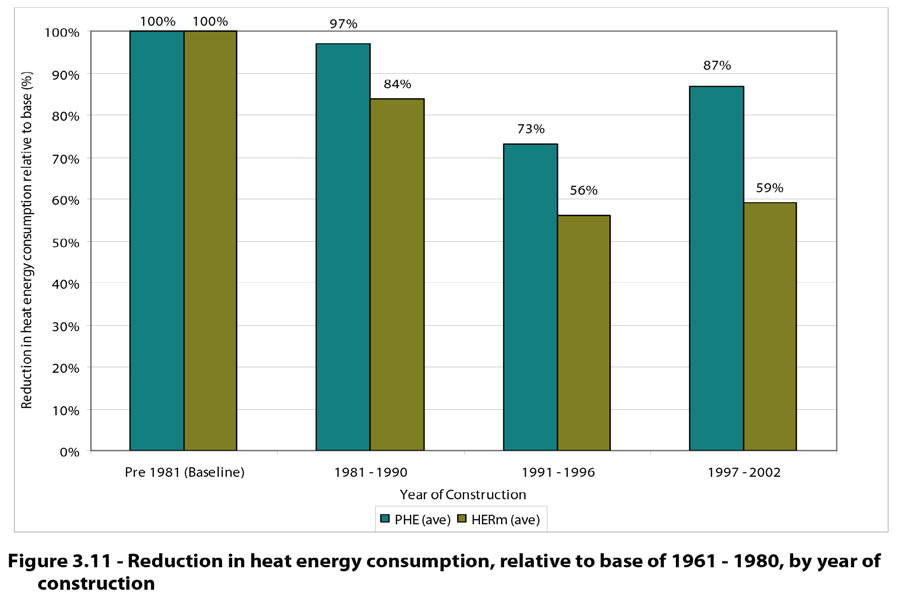

The 150 homes in the study were divided up by age band, with two to three years worth of actual purchased heat energy inputted and compared against the calculated usage in a modified version of the Heat Energy Rating (HERm) tool, a precursor to Deap. This led to a remarkable finding: actual purchased heat energy use was getting progressively lower in each newer age band as expected, with the exception of the newest homes in the sample, which were built post-1997 improvements to insulation standards, but which nonetheless registered a 16% increase in purchased energy use (whereas the HERm showed a projected 3% increase, which the report explains is within the margin of error, and “can be attributed to the changing mix of built form types between the two periods.”) The report also noted that while the theoretical heat energy use of the post-1997 homes was 41% lower than the pre 1981 baseline, the purchased heat energy was a mere 13% lower than that baseline, adding that: “There is also a trend of increasing difference between theoretical and actual heat energy consumption in newer housing.”

This study, which included other alarming findings with regard to endemic non-compliance with building regulations, and either missing insulation or cold bridging problems in 19 of 20 homes subjected to deeper analysis, was never published. Nor did it lead to follow-up studies to check whether some of the worrying trends and non compliance issues worsened or improved as the construction boom advanced and, eventually, crashed, and as ambitious new energy performance standards were introduced for homes in 2008 and 2011.

The only data we have – as per this study – indicates a widening gap between theoretical and actual heat energy use. I don’t doubt that standards of workmanship have improved in Irish construction recently with regard to energy performance. That’s borne out by the fact that the average airtightness test result for new homes has improved significantly from the average of 11.8 m3/hr/m2 at 50 Pa for the 28 post-1997 homes in the Energy Performance Survey of Irish Housing that were subjected to airtightness tests, to 3.6 m3/hr/m2. But the point remains: the only evidence we have that included actual energy use of a representative sample of Irish homes shows a substantial and widening gap between calculated and actual energy use. It’s impossible to say whether homes built to 2011 Part L will perform close to the calculations, and we’re equally in the dark about NZEB. The evidence shows that passive houses on the other hand, as identified in numerous monitoring studies, tend to perform remarkably close to their calculated levels – a fact that’s all the more remarkable given that their calculated space heating use is so low.

It remains to be seen what approaches other than the passive house standard pass the equivalence test for the planners in Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown. The insertion of the “or equivalent” clause was not a tokenistic reference on my part. Frankly I don’t care whether people build to the passive house standard or not. For me it’s rather a matter of ensuring that new buildings are built to achieve equivalent performance levels as passive house under a range of key indicators – both for the sake of the occupants and the environment, and to ensure that Ireland doesn’t waste money attempting to solve the housing crisis by building uncomfortable, wasteful, unhealthy buildings.