- Insight

- Posted

Why Dublin City’s passive house policy must be retained

The attempts to derail Dublin City Council’s proposed ‘passive house or equivalent’ planning requirement are bad news in the increasingly difficult fight to mitigate against and adapt to climate change – they risk being complicit in new buildings in the city breaching European law.

This article was originally published in issue 17 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

2014 was the warmest year on record. Then 2015 was. 2016 is tipped to be warmer still, according to UN agency the World Meteorological Organisation.

David Carlson, director of the WMO’s climate research programme, spelt out the situation at a news briefing in July: “What we’ve seen for the first six months of 2016 is really quite alarming. We would have thought it would take several years to warm up like this. We don’t have as much time as we thought.”

According to the WMO, June was the 14th consecutive month of record temperatures for land and oceans, and the 378th consecutive month with temperatures above the 20th century average.

The average temperature in the first six months of 2016 was 1.3C warmer than the pre-industrial era in the late 19th century, according to Nasa – remarkably close to the 1.5C target agreed by the world’s governments at the Paris climate talks to attempt to stave off the worst effects of climate change.

Carbon dioxide concentrations have passed the symbolic milestone of 400 parts per million in the atmosphere so far this year. “This underlines more starkly than ever the need to approve and implement the Paris climate change agreement, and to speed up the shift to low carbon economies and renewable energy,” said the WMO secretary general, Petteri Taalas.

In light of the seriousness of the situation, there is an urgent need to implement policies that combine two features: they must be reliable ways of delivering dramatic emissions reductions, and they should inspire others to follow suit.

Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council’s decision in April to require the passive house standard or demonstrably equivalent approaches as a planning requirement for all new buildings in the county is a shining example of such a policy.

Any local authority seeking to play its part in answering the WMO’s call for radical efforts to reduce carbon emissions would be wise to follow the recommendations of another UN agency, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, whose latest report on climate change mitigation options, AR5, placed particular emphasis on the passive house standard. The table at the start of the buildings chapter which summarizes the chapter’s main findings organized by major mitigation strategies lists the passive house standard as the first option in terms of system (infrastructure) efficiency. Endorsements really don’t come much better than that.

As passivehouseplus.ie reported at the time, Dublin City Council voted at the end of May to retain a policy in the draft city development plan requiring the passive house standard or equivalent for all new buildings in the city, in an early sign that Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown’s initiative could serve to inspire others. But although the policy was voted through by a near unanimous 35 to 4 majority, city planner Jim Keogan had notified councillors prior to the vote of potential legal concerns over the policy, and argued that he couldn’t put such a policy in the plan. The amended draft plan was duly published without the policy, though the possibility remains that it may be reintroduced into the final plan.

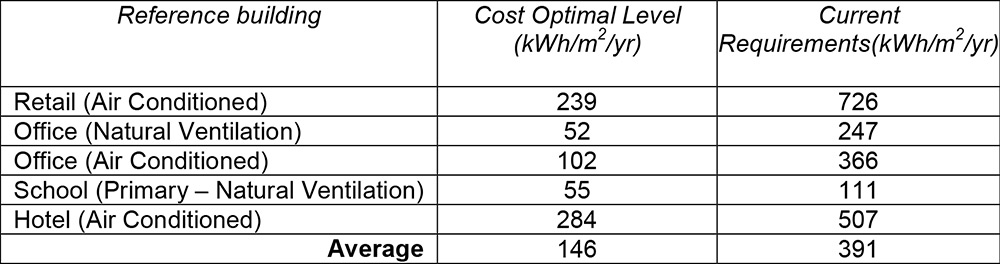

If successful, the decision to remove this policy means that new non-residential buildings in the city will be brought back to minimum energy performance and carbon emissions targets under Part L of the building regulations that by the state’s own admission fall substantially short of the cost-optimal energy efficiency requirements set out in the recast EU directive on the energy performance of buildings, as a 2013 report Ireland submitted to the commission on its progress in implementing these requirements made clear. For new non-residential buildings, this included an analysis of five diverse building types, comparing calculated energy use based on achieving cost-optimal levels versus minimum compliance with current regulations. The proposed cost-optimal targets for the five buildings averaged a primary energy target of 146 kWh/m2/yr, rising to an average of 391 kWh/m2/yr if built to current regs – 168% worse.

Given that EU law takes precedence over national law, that’s a serious issue. What are the implications, if a local authority rejects the will of its democratically elected representatives to use an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change-endorsed standard to tackle climate change, and in so doing permits buildings to be built to a standard that falls so woefully short of EU requirements designed to tackle climate change?

To give a sense of quite how bad the status quo is, the wall, roof and floor U-values specified in TGD L 2008 (buildings other than dwellings) are substantially worse than the requirements in 2002 TGD L for dwellings.

Yet those substandard requirements still apply today. The word is that the Department of Housing plans to finally update the requirements for non-residential buildings imminently, but that will entail a lengthy process, including a regulatory impact analysis being conducted and a draft regulation being published and sent out to consultation. It looks virtually certain therefore that the new requirements won’t come into force till 2017, and probably not till summer 2017, if not later.

Buildings should be designed to have regard not just to overheating risk today, but to the impacts of extreme weather events including higher risk of overheating within their lifespan.

But whatever final version is agreed will include a transitional arrangement, and the department is on record that the next revision for non-residential buildings will enable developers who applied for planning prior to the new requirements coming into force to build to the old requirements for two years. In effect that means that many non-residential buildings may be built to substandard 2002 insulation standards up till 2019.

But even this may be a best case scenario. The department has repeatedly broken its own deadlines on Part L updates. The department announced at the 2010 See the Light conference in Dublin that the requirements for non-residential buildings were due to be reviewed in 2011, and a 2012 departmental report, Towards Nearly Zero Energy Buildings in Ireland: Planning for 2020 and Beyond promised the revision of TGD L for non-residential buildings in 2013/14.

So based on past form, there is no reason to assume that the department will manage to update the requirements for non-residential buildings any time soon, notwithstanding the fact that the urgency of the housing crisis is such that the department’s focus is likely to be elsewhere.

To make matters worse, the nearly zero energy building deadlines are closer than they appear. Article 9 of the recast directive states that “Member States shall ensure that:

(a) by 31 December 2020, all new buildings are nearly zero energy buildings; and (b) after 31 December 2018, new buildings occupied and owned by public authorities are nearly zero-energy buildings.”

The directive makes no allowances for derogations or the kinds of transitional arrangements that accompany Irish building regulations changes.

In its 2012 NZEB report, the department stated with regard to non-residential buildings that “The final target for Nearly Zero Energy Building will be in the order of approximately 60%, defined in 2018 for public sector buildings and specified in regulation in 2020 for all buildings.” Consider the 2018 public buildings deadline. It’s mooted that the department, having repeatedly missed its deadlines for updating non-residential Part L to comply with the cost-optimal targets, plans to go straight to NZEB standards.

Suppose the revision to TGD L for non-residential buildings comes into force in, say, July 2017, with a transitional arrangements target of, say, 31 December 2018 for buildings owned and occupied by public authorities. This would mean that if a planning application was lodged prior to the regulation coming into force, and if substantial work is completed – in other words if the structure of external walls has been erected – by 31 December 2018, the previous version of TGD L would apply. If the building was then completed after that date, it would be in breach of the directive. Similarly, suppose the department set a target of 31 December 2020 for all new buildings to be NZEBs, as the department’s NZEB report indicates may be likely. The directive requires that all new buildings must be NZEBs after that date. Will the state be responsible for widespread, clear non-compliance in 2021 with a requirement of an EU directive it has known about since 2010?

Taking all of this into account, why would Dublin’s city planner object to the passive house or equivalent policy? The main argument made by Keogan against the policy hinged on the fact that development plans are governed by the Planning and Development Act, and that the proposed passive house policy was a building regulations matter, and would therefore fall under a different statute – the Building Control Act.

Yet campaigning successes I’ve been involved with in the past tell a different story: several local authorities have in the past set energy performance requirements in development plans and local area plans. I assisted Fingal County Council in 2005-06 to pass a policy into local area plans that all new buildings should have a combined space heating & hot water target of 50 kWh/m2/yr – which then evolved into 60% energy and CO2 emissions reductions targets – along with mandatory renewable energy targets. Wicklow County Council then followed suit with virtually identical policies, before Dún Laoghaire- Rathdown County Council set a target of 40% energy and CO2 reductions for new buildings under a variation to their 2005-2010 county development plan in 2007 – a feat they outdid earlier this year by adopting the passive house or equivalent policy I worded. But Dublin City Council also have form in this regard: in 2007 they too passed a variation, to the 2005-2011 city development plan, requiring B1 BERs for new buildings, rising to A3 BERs from 2009. The requirement applied to residential developments of 10 dwellings or more and for non-residential and mixed developments of 1,000 sqm or greater floor area.

On the one hand Jim Keogan states that setting energy performance standards is a building regulation matter, while on the other hand he recently justified the 2007 variation – made when he was deputy city planner – as an interim measure until the amended Part L came into effect. If the planning act doesn’t permit these kind of measures – and I would strongly contend that it does – then the council couldn’t put an energy performance target into a development plan, irrespective of whether it’s an interim measure or not. It’s also worth noting that energy performance targets for non-residential Part L weren’t updated after the 2007 “interim” Dublin City measure – meaning that new non-residential buildings in Dublin City built from 2011 until the NZEB target is fully implemented at some stage post 2020 represent a backwards step – and far more pollution than the requirements which applied from 2009 to 2011.

Notwithstanding the fact that the Planning and Development Act includes no statements that would prohibit the setting of energy performance, comfort, indoor air quality and carbon emissions reductions aims for buildings, section 10(2)(n) of the Planning and Development Act 2000 as amended, is important. It states that a development plan shall include objectives for:

“(n) the promotion of sustainable settlement and transportation strategies in urban and rural areas including the promotion of measures to— (i) reduce energy demand in response to the likelihood of increases in energy and other costs due to long-term decline in non-renewable resources, (ii) reduce anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and (iii) address the necessity of adaptation to climate change; in particular, having regard to location, layout and design of new development.”

The use of the word design here is interesting. There’s also a significant clause in the 5th schedule of the act, which establishes conditions which may be imposed on the granting of permission to develop land, without compensation, and which also bestows local authorities with the following power to establish conditions:

11. Any condition relating to […] (c) the promotion of design in structures for the purposes of flexible and sustainable use, including conservation of energy and resources.

This appears to give local authorities enormous scope to set a target such as passive house as a planning condition, ideally in support of requirements in a development plan.

Design is also mentioned in the key paragraph on energy efficiency under building regulations, Part L1, as amended under SI 854 of 2007:

A building shall be designed and constructed so as to ensure that the energy performance of the building is such as to limit the amount of energy required for the operation of the building and the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with this energy use insofar as is reasonably practicable.

At what point does design begin and end? Surely it begins prior to a planning application being made, and continues long after permission has been secured through to detail design and, due to the common need to make amendments on site, often continues even as completion approaches.

But does the word “design” mean one thing in the aforementioned sections of the planning act, and another in Part L, even though in both cases the reference to design is with regard to reducing energy demand and carbon emissions?

There is a strong argument that a passive house or equivalent policy would both enable the council to ensure that new buildings in the city satisfy the requirements of Part L1, and that omitting the policy would result in developments which don’t meet 10(2)(n) on the planning act. The point is that decisions taken prior to submitting a planning application – location, layout and design, to paraphrase 10(2)(n) - which are variously completely or partially ignored under the Building Control Act, have a substantial impact on all three elements of section 10(2)(n) – energy demand, carbon emissions and climate change adaptation.

It’s indisputable that planning decisions substantially impact on a building’s energy performance and associated carbon dioxide emissions, and the associated construction costs. This includes the location of the building(s) on a given site, relative to other structures which may create shelter or shade, and to the sun, as well as building shape. More compact form factors (external surface area to internal volume ratios) mean lower heat loss and lower construction costs per sqm. Glazing ratios and orientation are also significant impacts.

Failure to consider these factors at planning stage will more than likely lead to increases in terms of energy use, carbon dioxide emissions, construction costs, and risk of dangerous summer overheating. Moreover, it is insufficient to rely on general planning guidance on the likes of building form and orientation, and then entirely separate building regulations to influence detail design once planning is secured, precisely because of the resultant disconnect between planning and building.

Neither the Deap methodology nor the building regulations for dwellings make any attempt to quantify overheating risk or cooling need – in spite of the fact that this is a binding requirement of the recast energy performance of buildings directive. And the failure to consider the likes of location, orientation and form in Part L and Deap also lead to sub-optimal energy demand & associated CO2 emissions, and missed opportunities to reduce construction costs.

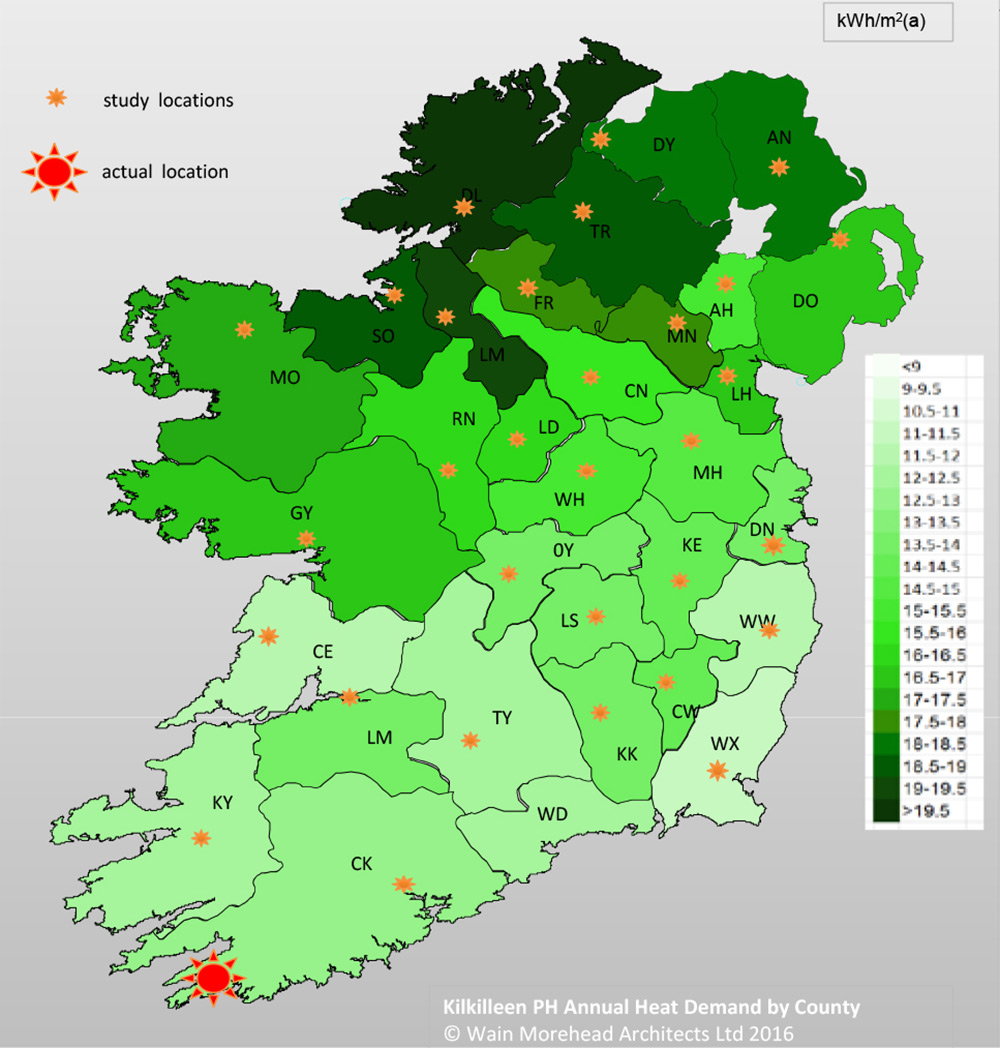

Analysis by Wain Morehead has shown that the space heating demand of a West Cork-based passive house designed by the firm rises from 11.5 kWh/m2/yr to over 19.5 kWh/m2/yr when moved to Donegal

A more integrated approach to design in planning & building control is key to reducing both energy demand and construction costs. It is revealing that the passive house design software, PHPP, actually stands for the Passive House Planning Package. This reflects a recognition that reducing energy demand starts at the initial design stage, before a planning application is made.

In terms of layout and building form, the reality of course is that certain forms of buildings are far more efficient than others. An apartment has far less heat loss than a detached house, as it has less external surface area through which heat can escape. And a cube shaped house has far less heat loss than a H-shaped house with the same floor area. This is ignored in TGD L, which just asks your H-shaped house to be 60% more energy efficient than if you’d built the same house plans to 2005 Part L. Thus the H-shaped house may comply with a B1 BER of 80-90 kWh/m2/yr, whereas a mid-mid apartment may need to hit an A2 BER and circa 45 kWh/m2/yr or better. This begs the question: if major design decisions that effect energy consumption have no bearing on meeting TGD L, can it truly be said that TGD L – a non-binding guidance document – is sufficient to ensure compliance with the requirement in Part L1 to design a building to such a standard as to limit energy consumption and carbon emissions “in so far as is reasonably practicable.” This is not to argue that buildings should be designed as cubes or spheres so as to limit energy use, but rather to set targets that reward more energy efficient designs, and ensure less efficient designs compensate by meeting higher specs to achieve a similarly low energy result.

In terms of location, Part L relies on the Dublin Airport weather files inputted into SEAI’s Deap software for every house in the country. Whereas PHPP currently includes five default regional weather files for Ireland, and permits the use of county specific – or even site specific – weather files. Architect John Morehead has shown how the West Cork passive house featured in this issue sees its space heating demand go from under 11.5 kWh/m2/yr to over 19.5 kWh/m2/yr when moved to Donegal. And although Dublin City Council may be close to Dublin Airport, profound differences can occur on different sites. (Morehead also noted 45% differences in heat load for the same building if sited in different parts of Cork.) Most obviously a south-facing site may perform very differently to a north-facing site. And then there’s altitude, proximity to the coast, how exposed a given site is, or to what extent adjacent structures cast shadows – a particular issue in urban areas of course – and the urban heat island effect. These sorts of issues can have profound effects.

And then there’s the adaptation to climate change requirement in Section 10(2)(n)(iii) of the planning act. Dr Mathilde Pascal’s doctoral research , as well as a more recent paper Pascal co-authored by Prof John Sweeney, on the risk of increased excess summer deaths as a consequence of climate change has helped highlight the issue, whereas the UK’s Zero Carbon Hub’s reports on the risk of overheating in low energy buildings – where due design consideration is not taken to avoiding overheating – indicate that this is an issue that urban councils in particular must address, due to the added impact of the urban heat island effect.

Buildings designed today should be designed to have regard not just to overheating risk today, but to the impacts of extreme weather events including higher risk of overheating within their lifespan. The building regulations for dwellings don’t attempt to quantity overheating risk. Passive house does. It sets a maximum temperature target – the building must be designed not to exceed 25C for more than 10% of the year – and it can integrate future weather files too. For instance, Exeter City Council designs all of its buildings to the passive house standard, using 2080 weather files.

In addition to increasing the risk of avoidable excess summer deaths, failing to ensure that building design addresses overheating risk invariably will also risk people retrofitting air conditioning systems in many cases, which will expose them to avoidable energy costs, and cause the buildings’ energy demand and associated emissions to rise.

Climate change is set to be the defining challenge for humanity in the 21st Century, and perhaps in any era. We can ill afford to miss clear opportunities to tackle this challenge for the sake of political and procedural expediency.