Mike Eliason

Mike Eliason

- International

- Posted

Big picture - Points of access to resilient living

Mike Eliason, architect, founder of Larch Lab and author of the must read Building for People, reflects on how a series of personal and global crises – from pandemic lockdowns and climate disasters to urban housing challenges – shaped his mission to bring sustainable, community-focused, and climateadaptive neighbourhoods to North America.

On 13 March 2020, while I was in the process of moving back to the US from Bayern, where I had been working, I became stuck: with the Covid-19 pandemic worsening across the EU, Trump closed the US borders. He did this while I was sleeping, meaning I woke up to dozens of messages – emails, texts, social media DMs, missed phone calls – asking how I was getting home. Unaware, I laughed: “My flight home is in a few days – what are you talking about?”

This kicked off a strange year in which trauma became the norm. A few days later, repatriation flights were set up, and I flew back to the US, directly into pandemic lockdowns. Our kids were (barely) learning on computers in our new home – where we also would be working.

In June of 2020, the George Floyd protests kicked off across the US. In Seattle, police used tear gas against protesters in a dense neighbourhood, affecting residents who were in their homes.

Biking with the kids around Munich. Photo: Heather Eliason

September 2020 saw dense, toxic wildfire smoke blanket the Seattle area for nearly two weeks, as our state saw some of the worst wildfires in its history. We were lucky that our home had decent filtration in our ventilation system, but being trapped inside for nearly two weeks with kids who were already largely indoors due to the pandemic and online learning was difficult. To this date, I now notice even the faintest molecule of wildfire smoke. Clearly, there’s a bit of PTSD related to this trauma that overwhelms me.

And then, in June of 2021, a massive heat dome settled over the Pacific Northwest, leading directly and indirectly to the deaths of up to 1,400 people. While not a passive house, our home is relatively protected from direct sunlight thanks to generous overhangs and trees. Our climate in Seattle is incredibly mild, such that we sometimes need sweaters on summer evenings, and night flushing has always been reliable.

The heat dome was different. Not only were the daytime highs more intense than anything we had experienced, but the nighttime lows, which normally range from 55-60F (13-16C) never really dropped below 20C. It was unbearable, and we were fortunate to be able to stay with a relative who had air conditioning, not to mention room for us. I have friends who were living in south and west-facing single aspect studios in new buildings that never saw their homes dip below the mid-80s at night – 29 degrees Celsius!

Path through a semi-permeable perimeter block in Freiburg's Rieselfeld ecodistrict. Photo: Payton Chung

Just two weeks earlier, I had been on a local housing panel where a distinguished developer stated we didn’t need air conditioning due to the region’s cold evening temperatures. The heat dome shattered that long held belief. We do not have an active solar protection industry in the US, external shades are rare for multifamily housing and most apartment buildings here don’t have air conditioning either – though that is slowly changing.

Throughout this period, I had a lot of time to reflect on the trauma and events from the last 16 months: time to look back on what I had been working on in Germany, why we had moved there in the first place (in part, to be closer to the global centre of mass timber and of passive house communities).

I also began to reflect on how those projects were so different to anything I was working on back in the US. I had already been researching how building codes affect housing design in different countries, and started to connect the dots on building codes, how they interface with land use codes, and what that means in terms of livability, quality of life, and climate adaptation.

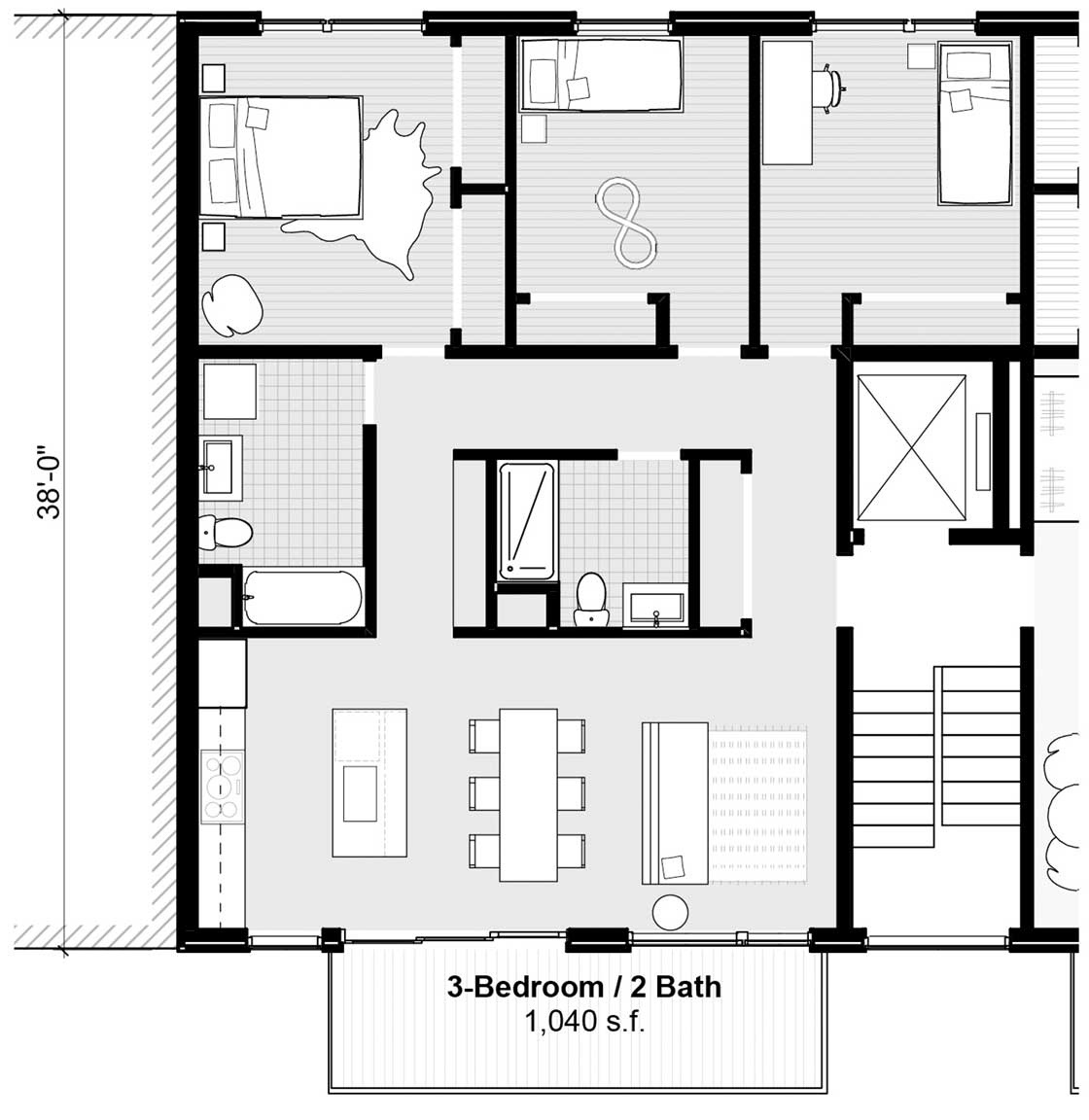

Floor plan for Larix, a proposed six-storey Point Access Block, allowing for family-sized homes, units that cross ventilate, and bedrooms positioned on the quiet side of the building. Image: Michael Eliason/Larch Lab

Out of that research and reflection, came the desire to have a stronger voice in highlighting the deficiencies of the status quo. We have a growing housing affordability crisis in much of the US, and lack the ability to scale up the development of affordable and climate adaptive homes. When it comes to passive houses, it feels like we are still light years behind Europe.

We aren’t very intentional in how we develop places and neighbourhoods – either over time, or from scratch and our development patterns ignore centuries of urban history, eschewing common sense approaches for buildings designed by excel spreadsheet to maximise yields at what seems like the greatest expense to comfort and quality of life.

I yearned to re-connect what I was working on and talking about in the US – with my roots and experiences working in Freiburg and Bayern. I had founded Larch Lab as an architecture and planning studio in 2021 to focus on decarbonised buildings and community- oriented housing, as well as to function as an urban think-tank working on advocacy, education, sustainable mobility, and climate adaptation.

In the lulls, I re-read my worn copy of Catherine Bauer’s Modern Housing (1934). Bauer was a leading member of the ‘houser’ group of planners who advocated affordable housing for low-income families. I was immediately struck by a single sentence: “Moreover, modern housing provides certain minimum amenities for every dwelling: cross-ventilation, for one thing; sunlight, quiet, and a pleasant outlook from every window”.

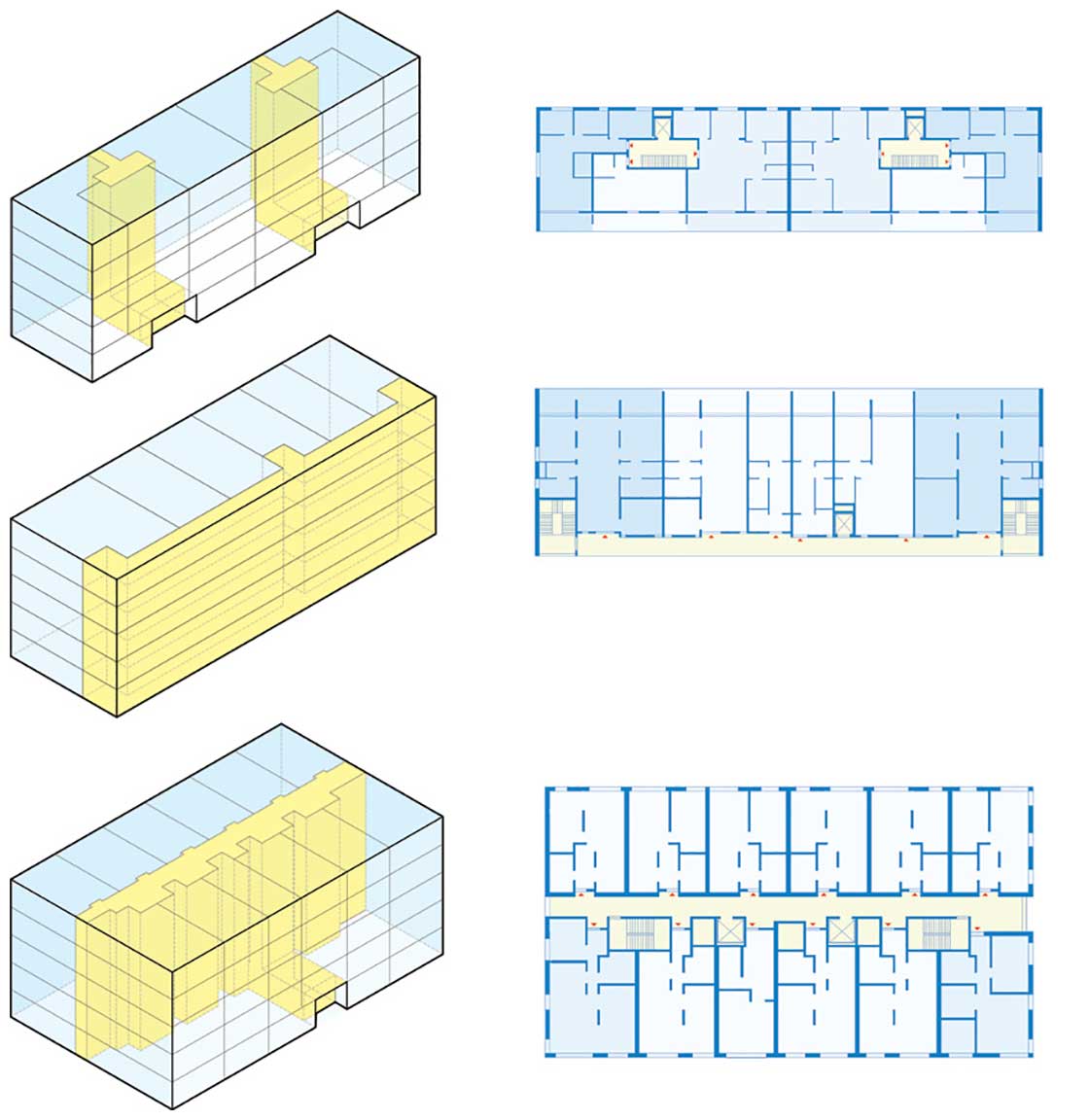

Unit access (top - Point Access Blocks, middle - Single Loaded Corridors, bottom - Double Loaded Corridors) plays a significant role in the livability and climate adaptation of a building. Image: Michael Eliason/Larch Lab

This article was originally published in issue 49 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

This was a profound, and succinct counterpoint to the aspects of housing built today. Due to our anomalous building codes, our multi-family housing generally uses a double-loaded corridor for unit access. This also results in narrow and incredibly deep units with windows only on one end, or if you are fortunate enough to live on a corner the possibility for daylight on two sides. These buildings cannot cross ventilate. Often, they are built just a few feet from property lines, with a similar building standing the same distance on their side of the property line. Consequently, there is little to no access to air, to sunlight, to pleasant views.

Building codes in the US and Canada are wildly anomalous from peer countries, resulting in buildings that are often much larger and deeper – and with homes that are much more compromised.

The workhorse for moderately dense urban housing is the single stair building, or as I call it the Point Access Block. These are found all over European cities, from small multifamily buildings on the outskirts, to dense perimeter blocks and high-rise towers. These buildings induce larger family-sized units and a more diverse unit mix, often in buildings with a far thinner building depth than we see in the US. This has the added benefit of allowing more courtyard or open space as well. Point Access Blocks allow for better daylight in homes, and often the ability to cross ventilate, as most units are dual or corner aspect.

A dual aspect three-bedroom dwelling in a European point access block is a radical departure from US construction. Image: Michael Eliason/Larch Lab

However, Point Access Blocks are effectively illegal in the US above three storeys, with a handful of exceptions. The end result of this is that homes in US and Canadian multifamily buildings are far unlike anything being built in the rest of the world, and they are a poor substitute for other types of housing such as detached homes or rowhouses.

Increased development costs, overly permissive land use codes, and rising interest rates have also resulted in a preponderance of massive buildings, often with over 150 units – and most of those units being small studios or one-bedroom homes. In Seattle, less than two per cent of new apartments have three or more bedrooms. Windowless bedrooms have become common in many cities where they are not specifically restricted. I have even seen projects under construction in Seattle with three-bedroom homes on a re-entrant corner where none of the bedrooms have windows, with the entire unit only having one small wall of windows looking onto a tiny courtyard.

Housing built today is a radical departure from the very types of projects Bauer was writing about in 1934, and not just in a quantitative sense. Much housing built today is being built in a manner that is car-centric, exacerbating climate change, and on top of which, the majority are not built to adapt to a changing climate.

In much of the US, we concentrate dense, affordable housing on arterial roads and highways, in order to preserve detached housing and sprawl off of them. Even Transit Oriented Developments – neighbourhoods around high capacity and frequent transit – are generally sited near highways or at the intersections of major roads. There is typically no comprehensive planning or mobility strategy, so instead of providing space for community and nature, these neighbourhoods are still largely autocentric and loud.

US arterials and highways are the types of streets where dense affordable housing is legal.

It doesn't have to be this way

We can chart a path to adequate affordable housing that prioritises a better quality of life, not to mention ecology, adapt to climate change, and better connect our communities to address the growing social isolation crisis that has only exploded in the aftermath of the pandemic.

The passive house community was one of the first to realise the benefits to reducing operational emissions, and then pivoted to reducing embodied carbon emissions. Many of my friends and colleagues in this world are doing incredible work with straw, wood, and other bio-based products. There is also an incredible effort around retrofits, rehabilitations, and so-called aufstockungen (vertical additions or top ups to existing buildings).

These are all great, and I continue to believe that the passive house community is on the bleeding edge of all things related to efficiency and carbon.

The realisation that this issue didn’t just affect housing, but infrastructure and quality of life, and was strongly connected to public health outcomes really pushed me to start to connect the dots for solutions and frameworks to these problems.

The following strategies are ones that I believe we should be focusing on to create dense, walkable, low carbon neighbourhoods offering a high quality of life and positive public health outcomes in the face of a changing climate.

EcoCocon’s low carbon passive house-certified exterior straw and wood wall panels. Photo: EcoCocon Straw Wall System

Compact, climate-adaptive, and nature-inclusive ecodistricts

Ecodistricts are ecologically oriented districts, such as the oft-cited Bo01 in Malmo, or Freiburg’s Vauban. They are typically brownfields redeveloped into socially mixed and ecologically focused neighbourhoods. They come in a variety of sizes and scales – from small settlements to massive projects like Vienna’s Seestadt, built over the former airport, with homes ultimately for 25,000 people and space for 20,000 jobs.

The integrally planned ecodistrict should be a district of blocks or neighbourhoods that facilitates sustainable and future-oriented mobility (think bikes and e-bikes) – over broad streets designed for cars. Traffic calming is carried out to ensure these places are safe for everyone, from children to elderly residents. These districts are usually oriented around transit and bicycle mobility to reduce car reliance. Schools, pre-school care, cafés, and grocery stores are also quite common, helping to facilitate walkability and low carbon living.

Priorities for climate adaptation should include flooding and rain inundation, incorporating sponge city principles and abundant trees and green space to mitigate overheating.

The focus on climate adaptation in these neighbourhoods will lead not only to better public health outcomes but to better quality of life for residents as well, as they have access to nature and resources within reach without needing to hop in a car for everyday tasks. Cities that prioritise climate adaptive places offering a high quality of life, high quality public realms, open space, and car-light and even car-free neighbourhoods – will find they are lighthouses in the future of sustainable urban development.

Car-free paths connect to abundant social housing in Vienna’s Sonnwendviertel ecodistrict. Photo: Mark Ostrow

‘Baugruppen’ and collaborative housing

Baugruppen’, German for building groups, are a form of collaborative housing where the people who will live in a multi-family building come together to co-participate in the planning and development process.

Collaborative housing can include a variety of forms of housing (condominiums, co-operatives, apartment buildings, rowhouses, townhouses, and so on) developed by the residents that will be living in them, rather than by developers. The elimination of developer profit and marketing costs can result in significant savings – from ten to twenty per cent – over market-rate housing. Possibly more with better land disposition properties prioritising collaborative housing.

Collaborative housing is a value-driven approach in which residents prioritise the levels of ecology and social spaces they want and need over the profit motive. Dr. Wolfgang Feist’s passive house in Kranichstein – the first multi-family passive house building – is itself a ‘baugruppe’. Mass timber was being incorporated in collaborative housing years before anyone in the US, other than a small handful of people, were even talking about it, including Kaden Klingbeil’s stunning seven- storey mass timber building in Berlin.

Freiburg's car-light Vauban ecodistrict is filled with numerous Baugruppen. Photo: Payton Chung

Passive house as a baseline to healthy, climate adaptive homes

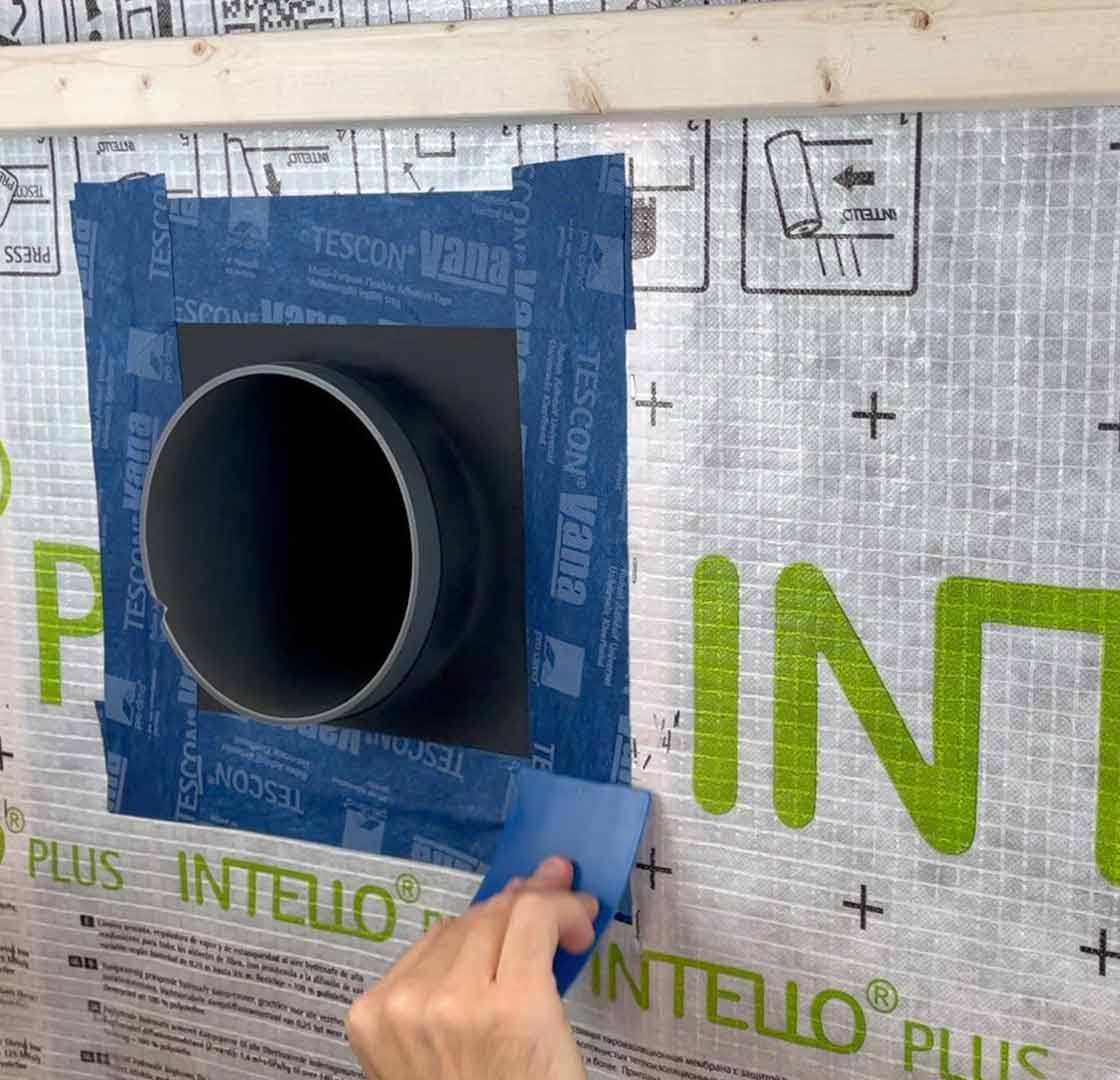

Despite taking the passive house training course in 2010, I personally never really connected the dots to how passive house designs could provide the kind of dwelling that could expand the bounds of habitability in a changing climate. It took a series of conversations with my dear friend Monte Paulsen over the years, debating these very topics, the merits, the trade-offs, the benefits. It was Monte who pointed out the wildfire smoke protection benefits that come from an airtight building envelope, high performance windows, and fresh, filtered ventilation.

And he had the data to back it up. Furthermore, passive houses are a buoy against energy poverty, as well as allowing for smaller mechanical systems and lower replacement costs down the line as efficiencies in HVAC improve over the decades.

The designs radically reduce mould risk from condensation and vapor transfer. Residents in passive house-spec social housing in the UK have even noted a reduction in the severity of asthma and other illnesses over where they previously lived.

Indeed, the improved air quality benefits of passive houses are well noted, and it is fair to say that the pandemic brought healthy air to the forefront in a manner I hadn't really anticipated. While it has not resulted in an explosion of passive house buildings, there is at least a growing awareness that the way we have been designing buildings actively puts people at risk.

Owing to the power of PHPP (the Passive House Planning Package) – we can not only test to see how our buildings will perform in a warming world – but what efforts can be done to really design out the heat. Heat due to climate change is a growing concern, and better understanding how this will affect buildings – buildings designed for a cooler climate that no longer exists – is imperative. Crucially, passive house buildings are so efficient that they need minimal active cooling to remain habitable, and cooling loads can even be shifted to offpeak durations to reduce demand on electrical grids.

The heat dome was a perfect event that focused a lot of our office’s efforts on prioritising passive house as a new baseline for ensuring greater resilience and adaptability moving forward.

Quiet, right-sized streets in Amsterdam. Photo: Mark Ostrow

Proactive governments lead

We all saw the success in Brussels of ramping up the uptake of the passive house standard, with visionary leadership and collaboration. Cities and states build and manage many buildings, and can mandate that new and retrofitted public buildings meet the standard. Quasi-governmental agencies can also show effective leadership. Neue Heimat Tirol and ABG Frankfurt are standouts in the world of social housing and limited profit housing associations leading with climate and passive house. Companies like these were the impetus for Seattle’s own Social Housing Public Development Authority, whose board I serve on, that is tasked with building affordable community-oriented housing.

Cities can take an active role in planning and land disposition to prioritise non-market housing. The City of Amsterdam owns 80 per cent of its land, and holds parcels aside in large developments for self-builds and multi-family buildings similar to baugruppen called Collectief Particulier Opdrachtgeverschap (CPO). Natrufied Architecture’s Wooncoöperatie De Warren is a low-carbon, energy-positive co-operative in Amsterdam that was developed on land the city reserved for affordable, community- oriented housing. Cities like Vienna, Freiburg, and Tuebingen similarly reserve land for community-oriented housing, and use a creative tendering process to facilitate even more incredible projects – bike-friendly mass timber housing, multigenerational housing, LGBTQIA-oriented, and even family-friendly housing incorporating housing for refugees.

Under Mayor Ann Hidalgo, Paris has seen a mobility transformation that seemingly daily is changing streetscapes and saving lives. Cities that foster car-light neighbourhoods will realise the public health gains are incredible – reduced noise pollution, reduced air pollution, safer streets and less traffic violence. Residents will find they have quieter neighbourhoods where they can actually hear birds instead of cars, find better sleep, and be more socially connected.

Gaskets and tape help to keep out cold drafts, moisture, and wildfire smoke. Photo: 475 High Performance Building Supply

The way we plan and build our cities and neighbourhoods is directly related to the quality of life in them. Our neighbourhoods will have a massive impact on our collective ability to rapidly adapt to climate change.

I used to think that we needed to imagine brilliant futures, but I have come to realise that these futures already exist within our collective knowledge and experience. They just have not been harnessed and synthesised anywhere near the levels needed to adapt to these tumultuous and changing times.

It is my fundamental belief that a better world really is possible and that with the right policies and leadership, we can ultimately unleash brilliant futures that foster more cohesive and socially connected communities; communities that prioritise ecology and create places in which we can thrive.