- New build

- Posted

Ecological Lake District passive house generates its own electricity

This new home in Cumbria not only meets the passive house standard, it embraces natural and recycled materials and produces its own electricity — and achieved it all on a ‘shoestring’ budget.

Back in the 1980s, it’s fair to say that British homes, old or new, were a bit on the cold side. But one young couple got a glimpse of the future when some family members imported a Swedish kit house. They were struck by how quickly it went up. It was properly insulated, had tripleglazed windows, and was warm. They were hooked on the idea of building something similar for themselves.

Fast forward to 2012, and a move to a village in the gorgeous Cumbrian fells finally gave the couple (who wish to remain private for this article) an opportunity to make that dream a reality, when they were able to buy a plot in the village they had chosen as their new home.

In the intervening years they had kept themselves informed: as members of the Centre for Alternative Technology they followed the progress of low energy housing design in the UK and internationally. Airtightness emerged as an issue alongside high levels of insulation, and then the passive house standard came on to the scene.

Because of their long-standing interest in sustainable low energy building, passive house was the logical approach. And passive house architects EcoArc, led by Andrew Yeats, were based just down the road. The couple became the first of EcoArc’s clients, after the Lancaster Co-Housing group, to move into a passive house. But EcoArc now have no fewer than 17 further passive projects in the pipeline.

The 41 homes at Lancaster were of masonry build, but this client chose to build with timber: “I’d done quite a bit of reading and knew there were plenty of timber-framed passive house builds, so we couldn’t see any reason why not; and we really wanted a building that could go up and become weathertight quickly.”

The roof features an Ampatop Protecta breather membrane outside the rafters to the timber structure

The client did some research and opted for a timber frame system delivered by Irish firm MBC. “We were looking for a firm who had an integrated system for floor slab and walls – as this is one of the trickiest junctions, it's important they work together properly. It may not necessarily be a problem if you have a worked-out design, but using a single system for both seemed to be useful to us – not least to avoid having two separate contractors blaming each other if it went wrong!”

Andrew Yeats initially had his reservations about using timber frame for passive house, for example over the possible lack of thermal mass, but he’s now a convert. “I’m now sold hook, line and sinker on timber frame. It’s just so quick to put up. At Lancaster, we struggled all through the winter in the frost, rain and muck. Timber frame is so much more manageable, quicker and cleaner,” he says.

Metal web joists create neat runs for MVHR ducting

Thermal mass has not proved to be a significant issue at the Cumbrian house – there is an insulated concrete slab under the reclaimed wooden floors, which provides mass. The wall system consisted of pre-constructed twin-stud panels, delivered to site to be taped then filled with pumped cellulose insulation.

The panels support the roof, allowing continuity of insulation and rapid weather-tightness. The frame was then sheathed with a rendered block wall around the ground floor and wooden cladding at first floor, both for aesthetic reasons and to create a clear cavity to ensure Cumbria’s driving rain does not get into the insulated fabric.

The finished building is a neat, compact house with a simple form, that was cost-effective to build and is very easy to heat. “It’s very comfortable, we had to get used to the even temperatures everywhere. There is no fire to sit next to, but it is very, very nice. Especially in cold weather, it’s lovely — immediately you are in the warm. The indoor temperatures average around 21 or 22 degrees, and it has never gone below 18,” the client says.

Pre-fit strips of airtight membrane ensure stud walls don’t pose an infiltration risk

The very low heat load is evident: “It warms up very quickly in response to the number of people here, or when we are cooking. It’s very efficient at keeping us warm.”

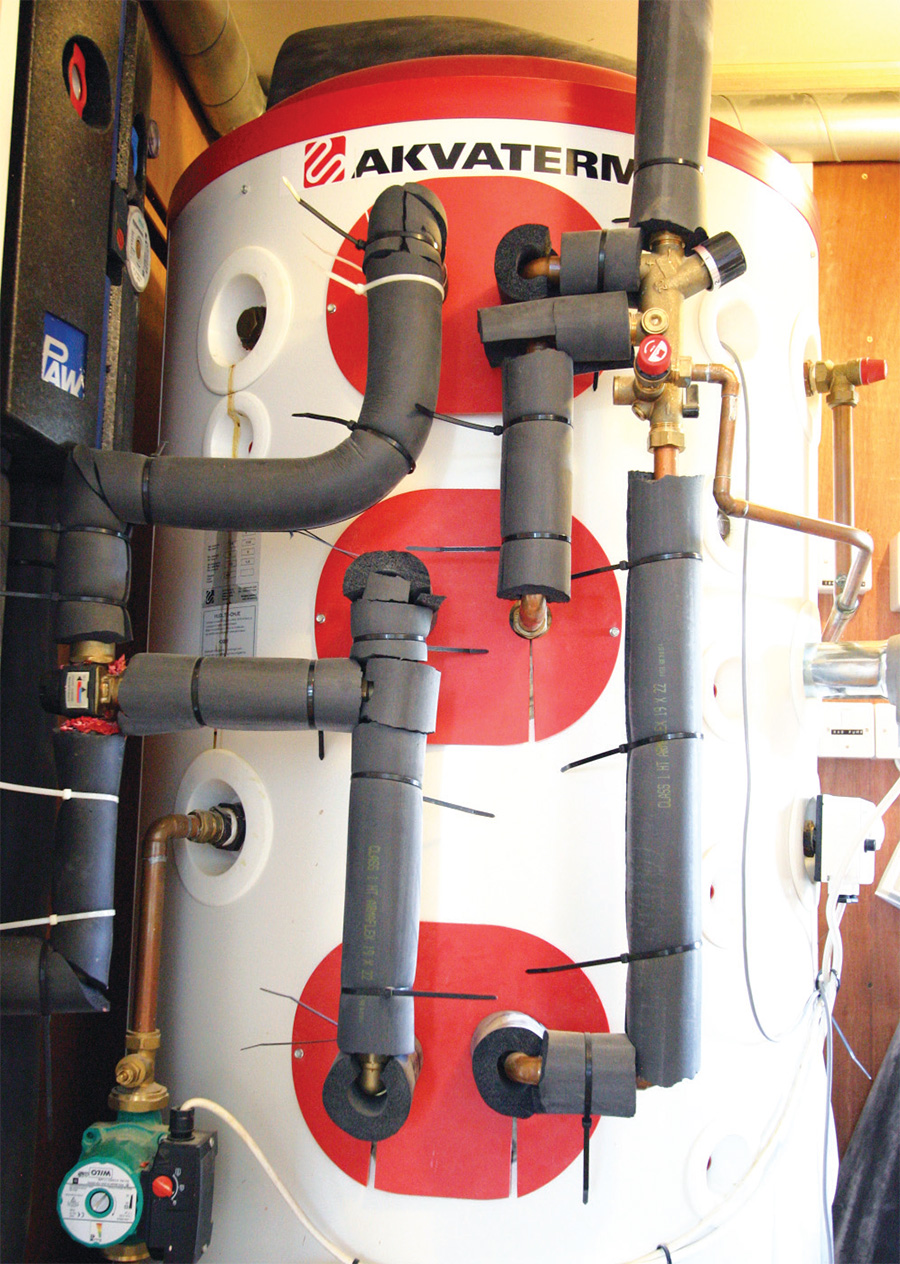

Passive house is known for minimal heating systems, and this build was designed and built according to the classic approach of an electric heating element in the ventilation supply ducts. However, the occupants prefer to manage without any direct heating as far as possible. Instead, like all passive buildings the house makes good use of solar gains and internal gains from people and appliances, then on top of this there is an almost-all-renewable contribution from the giant 500 litre thermal store at the heart of the house. The thermal store – whose primary job is providing domestic hot water — receives most of its heat from renewables on the roof.

The store is heated firstly by 7.8 square metres of solar thermal panels. If these are not keeping the tank hot enough, immersion heaters kick in, topping up the heat at times when the solar PV panels on the roof are generating electricity. If necessary, the immersion heater can also take advantage of ‘Economy 7’ low cost night-time grid electricity – but only between 2am and 6 am (and for the top of the tank only), just to ensure there is some hot water first thing in the morning.

500 litre Akvaterm thermal store

This has worked well, with most of the heat coming from the renewables, throughout the year. With all that heat sitting on the landing, even though the store is insulated, enough passes out into the living space to keep the house warm too, with direct electric heating only being deployed occasionally.

The client says: “It’s an all electric house, and although I haven’t kept close track of the running costs, I estimate we are using slightly less electricity than we are generating, so we are in energy balance more or less. We do need to make some minor changes to the system, as at the moment there is no heat dump for the excess hot water in summer, which can lead to the house overheating. It’s easy enough to deal with this by opening the windows, though.”

They are happy with the MVHR too: “We find it very straightforward. It’s extremely quiet, we like to ask our visitors if they can hear it, and they can’t. It’s tremendous – we’re very happy with it.”

The house is clad with silicone render on the ground floor and Eternit Cedral weather board on the first floor

Although this is only EcoArc’s second completed passive house project, Andrew Yeats admits he is now “very evangelical” about the standard – clearly with some success, as a large proportion of his subsequent clients have also commissioned passive builds. “When clients come to me, I tell them this is what we do: there would have to be a very good reason not to do passive house.”

One potential obstacle raised by EcoArc’s clients is cost. Having delivered cost-effective masonry build passive houses for Lancaster Cohousing, Yeats was keen to demonstrate cost-effective passive house in timber frame as well – and believes he has succeeded.

His Lake District clients needed to build “on a shoestring” after buying quite an expensive plot (this, says the client, is why they have not had the house certified – they just didn’t have the money left over).

The final build cost was £1370/m2. “Some architects would struggle to do a regular home for that,” Andrew Yeats points out. He believes this offers good value for a home that really performs. “After all, architects can be very good at spending other people’s money on things that don’t really mean anything!”

He continues: “We kept the costs down by the way we ran the contract. We have had terrible experiences with competitive tendering for passive house. Until they have enough confidence to price fairly for passive house, without the scare factor, virgin passive house builders tend to whack the rates up: they think of how much it will cost to build, then double it!

“So what we did was, the client employed the (mainly local) contractors for the separate trades — including some being paid on an hourly rate — and set up an account at the builders’ merchants. That way everyone was paid fairly, but no-one was making a massive profit. It came in on budget and on time.”

With no single contractor carrying the can for passive house quality, instead, they built in quality assurance separately. “We arranged it so that the timber framers would be paid only when the shell was airtight to below 0.6. For the insulation installation, we employed a local independent consultant to check the insulation fill thermographically as it was going in, to ensure there were no gaps. For the ventilation system, a local plumber did the installation, then Green Building Store came and commissioned it.”

Building on this positive experience, especially the speed of erection on site, EcoArc have started to work with a local timber frame firm, Eden Frame, to develop their own passive house timber frame system. “We do more of the construction offsite — the panels are pre-insulated, that makes it even quicker to erect. The panels then slot together with thermal bridge free dog-leg joints at the corners: there are not many joints though —the panels are really large,” Andrew says

“This means a frame can go up in one day, and the roof goes on the following morning.”

It isn’t just EcoArc, but the clients too, who hope more homes like this will be constructed in the area. In their design, access and environmental statement to the planning authority (the Lake District National Park) the clients stressed the need to develop housing solutions in the area that protect and sustain the environment – that means homes that are energy efficient, sustainable and cost-effective.

Their own house certainly shows just exactly how this can be done.

Selected project details

Architect: EcoArc (Andrew Yeats)

Timber frame: MBC Timber Frame Ltd

Contractors: Sam Nelson & Jim Crawford

Civil & structural engineering: Peter de Lacy Staunton

Passive house consultant: Passivate

Cellulose insulation: Warmcel

Glass wool insulation: Knauf

Quantity surveyors: Bushell Raven

Mechanical contractor: Nick Dent

Electrical contractor: Phillip Townson

Airtightness testing: Paul Jennings

Additional wall insulation: Kingspan Insulation UK

Airtightness products: Siga/Ampac

Windows & doors: Ecohaus Internorm

MVHR: Green Building Store

Solar thermal collectors: Consolar

Solar PV: Lakes Renewables

Thermal store: Akvaterm

Cladding: Marley Eternit

Building boards: Fermacell

Concrete block: Aggregate Industries

Rainwater harvesting system: Rainwater Harvesting Ltd

Additional info

Building type: Detached two-storey timber frame house with total floor area of 151.8 square metres (including garage and conservatory) Location: Staveley, Kendal, Cumbria, UK (Lake District National Park)

Completion date: June 2014

Budget: £208K

Passive house certification: pending

Space heating demand (PHPP): 15 kWh/m2/yr

Heat load (PHPP): 10 W/m2

Primary energy demand (PHPP): 112 kWh/m2/yr

Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.58 ACH or 0.52m3/m2/hr

Energy performance certificate (EPC): A (numerical score 104)

Thermal bridging: Bespoke cold bridge free junction detail design by Eco Arc. Extensive Psi-Therm 2D modelling by Passivate of all key junctions. Resultant calculated cold bridge PSI- value 0.02283 W/mK, fRSi-value 0.91.

Ground floor: 20mm reclaimed maple flooring, on 50mm battens with glass wool insulation between, on 100mm thick reinforced concrete floor slab, on 300 mm EPS insulation as part of Viking Passive Slab insulated foundation system (PHI certified). U-value: 0.105 W/m2K

Ground floor walls: 10mm thin coat silicone render, on 100mm recycled aggregate concrete block, on 50mm ventilated cavity, on wind-tight membrane, on 12mm sheathing board, on MBC 300mm preservative treated Larsen twin wall with full-fill Warmcel 500 cellulose insulation, on 12mm OSB to MBC/Viking House specifications with taped joints, on Siga Majpell airtightness membrane and vapour control layer, on 50 x 50mm battens to form service void insulated with glass wool insulation, on 12.5mm Fermacell board. U-value: 0.11 W/m2K

First floor walls: Eternit Cedral weather boarding, on 50 x 50 mm vertical battens to form ventilated cavity, on wind-tight membrane, on 12mm sheathingboard, on MBC 300mm preservative treated

Larsen twin wall with Warmcel 500 full fill cellulose insulation, on Siga Majpell airtightness membrane and vapour control layer, on 12mm OSB, on 50 x 50mm battens to form service

void insulated with glass wool insulation, on 12.5 Fermacell board. U-value: 0.11 W/m2K

Roof: Recycled slates externally followed underneath by ventilated cavity, Ampack Ampatop protect roofing membrane, on Bob tail fink truss rafters at 600 c/c with 620mm full fill Warmcel insulation, followed underneath by vapour control layer / air tightness barrier, 25 x 50mm battens to form a services void, 12.5mm on 12.5 Fermacell board. U-value: 0.065 W/m2K

Windows: Internorm KF410 triple-glazed aluminium clad windows and doors with ISO glazing spacers. Overall U-value: 0.72 W/m2K

Heating: 1kW electric heater element in MVHR duct. Consolar solar thermal system, consisting of three panels covering 7.8 square metres, delivering heat to 500 litre Akvaterm solar thermal store.

Ventilation: Passive House Institute certified Paul Focus 200 MVHR unit with short self insulated EPP ducts to outside. PHI certified heat recovery rate 91%.

Electricity: 4kWp solar PV system using 16 Hyundai 250W modules, linked to Immersun controller unit to transfer excess electric to Akvaterm solar thermal store.

Water: F-line Flat Tank 3000 litre underground domestic rainwater harvesting system kit with mains backup, overflow to 1m3 soakaways located in the garden.

Green materials: Recycled slate roofing, recycled maple timber flooring, cellulose insulation, FSC-certified timber, recycled stone for external patio & paths, recycled granite for external table.