- Insight

- Posted

Cold Truths: Part 2

Part one of this article mini-series explained how vulnerable people are likely to respond to the energy crisis this winter. But what will happen to occupant health when people cannot afford to turn the heat on, and how will low energy buildings fare?

“My kid has asthma so if the temperature isn’t right, she'll be coughing despite wearing jumpers. And when it’s really bad she will vomit due to coughing so much.” – Parent on chat forum (1)

“The colder it gets, the more intense [my joint] pain gets. And I sort of stiffen up. It’s a lot harder to move when it’s colder rather than being warm.” – Arthritis sufferer (2)

“I’m scared to go out and spend money, and scared to heat the flat when it’s cold. I can’t sleep at night for worrying, I keep crying and wonder how I’ll manage to keep going.” – Resident describing their situation to the Money and Mental Health Policy Institute

When people are cold in their homes, their health is at risk. Even just a couple of degrees cooling can change our physiology and impact our health. Low temperatures may also drive poorer ventilation and poorer indoor air quality.

This winter, far more people are going to be cold. Many will be unable to heat their homes at all. People are already in physical and mental distress. More people than ever – particularly those who are very young, very old, or already unwell or vulnerable – will become ill, many will be hospitalised. Some, sadly, will die: children as well as adults. The tragic death of Awaab Ishak, killed by the mould in his home in December 2020, is a horrible reminder of this(3).

The Institute of Health Equity warns that: “Cold homes have direct and indirect health impacts, including heart attack and hypertension, asthma and wheeze in children, avoidable hospital admissions, and poor mental health. The impacts are likely to be worse when combined with other hazards such as damp, mould and pests.(4)”

In 2019 Christians Against Poverty reported that almost one in five of the people they helped had gone without basic energy- dependent activities, such as cooking or washing, for at least two months. This will not have improved.

Impacts of underventilation and damp

When homes are cold and occupants are struggling to afford energy, the environment often becomes damper.

Relative humidity rises automatically when temperatures fall. On top of this, people are likely to reduce ventilation (which may already be inadequate) to try to retain what little heat they have.

Even if a home is warm, reduced ventilation is harmful: research has repeatedly demonstrated a link between lower ventilation rates and worse health(5). Moisture and other indoor pollutants are created by the normal activities of occupants. When people are struggling to dry laundry, or are using alternative, polluting heat sources, the situation is compounded. The colder the dwelling, the more the humidity rises, and the more condensation will form, increasing mould growth.

Other indoor pollutants such as NOx, cigarette smoke, volatile organic compounds and carbon monoxide, may all increase due to reduced ventilation. And if someone in the home is infected with an airborne virus (such as Covid) transmission may increase.

Together, all these effects drive a very large range of health harms. Babies and young children in homes with visible mould are at greatly increased risk of hospitalisation for lung infections, risking a “tidal wave” of hospital admissions this winter(6). Damp and mould may also cause eye problems, and cause or worsen eczema(7).

“The council gave us a dehumidifier, but it is still a big problem. We have black mould in the bedrooms. My parents are really worried, they clean it off but it comes back. It affects our skin and we breathe it in … the whole family has eczema now.” Shazia, 18, quoted in ‘Inside Story’, RCPCH

On top of all this, the stress of living in a cold, potentially mouldy home, and not having enough money to manage, can severely harm mental health in both adults and children.

Disability, dementia & long-term health challenges – what will happen to high needs households?

“Dad can't regulate his own temperature so relies on the heating being on 24/7... [the most recent] bill increase is terrifying.”

“My elderly dad has an electric bed, mattress, hoist, needs the central heating on all day and night and needs washing much more than what’s normal. Our monthly direct debit has doubled even without the price rises...”

- Comments on social media, responding to a discussion about energy prices, March 2022

People with illnesses or disabilities often need more heat than the rest of us. Many chronic and disabling conditions cause people to feel the cold more keenly, or suffer its impacts more severely. For example, people with spinal injuries are advised to keep their homes at 22 C, to avoid additional health problems(8).

If you are not able to move much, or you have a reduced appetite because of illness or treatment, including cancer, you are particularly likely to feel the cold. Cancer treatment may depress the immune system, compounding the risk from infections – already worse in the cold.

“My husband is suffering from cancer and having chemotherapy, because of that he feels very cold.” - “Better at Home” programme(9)

Sick or disabled people are likely to be at home a lot, so need more hours of heating. People with dementia may not notice they are cold, or they may not respond by putting on more clothes. Often, they lose sense of day and night, so require heating 24 hours a day to be safe.

In cold homes, elderly people and those with poor mobility are at more risk of falling, and of suffering irreversible harm when they fall. Falls at night when the home is cold and the person lies undiscovered, wearing only light nightclothes, are particularly dangerous.

A fall like this can trigger a rapid deterioration in physical health for any elderly person. This is all too often the prelude to a serious physical decline, and the end of independence. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation reported in 2020 that almost a third of disabled people were living in poverty(10). Even before the 2022 price rises, disabled people were struggling.

“There are disabled people whose condition means they need to keep warm, having only one meal a day. Others go without so their children can eat, live in a damp house, or wake up cold and go to bed early.” - Joseph Rowntree Foundation(11)

The situation is certain to be worse this winter. The soaring price of energy, plus the cost-of-living crisis, will leave people with disabilities and chronic conditions in the most desperate of circumstances. It will also affect their carers, many of whom are family members and unpaid (bar the small allowances they may receive from the state).

As the Northern Ireland Carers Association has warned, when bills go up to unmanageable levels, carers may need to leave their caring role and seek work elsewhere, simply to bring in enough money to cover household running costs. The stress will hit the mental health of both carers and those they care for, extremely hard(12).

The breakdown in these informal care arrangements is potentially catastrophic at a time when social care is already desperately under-resourced. If more households turn to barely available services for help, the result is almost certain to be deterioration in the health of disabled people, a rise in hospitalisations, and increased expense and pressure on statutory services.

Deaths in cold homes

The number of excess winter deaths in England and Wales is normally around 24,000 (Covid winters excepted). The strongest seasonal rise is in respiratory deaths, but winter death rates from cardiovascular disease, dementia and falls are also higher than the rest of the year.

An estimated 10-30 per cent of these deaths are attributable to cold homes – so, up to 7,000 deaths in a normal winter. As NICE warns, “in the coldest 10 per cent of homes, the death rate rises about 2.8 per cent for every degree the external temperature drops” in the warmest homes, the risk is one third of that(13).

More homes will be cold this winter, so we can expect more excess deaths.

Cold homes and mental health

The psychological impacts of cold, damp and fuel poverty are closely intertwined. Research has repeatedly showed that being unable to keep warm in winter, having mould in the home, and being in debt to energy companies increases people’s risk of mental illness.(14)(15)(16)

This year, Which? has reported that one in four adults reported having trouble sleeping because of worry about energy bills. More than half said they were feeling ‘very anxious’ about it(17).

For some the anxiety is already at crisis level. Gareth McNab from the debt crisis charity Christians Against Poverty said they were now seeing desperation, suicidality and people disclosing self-harm pretty much every day.

Young people, who have already been hit so hard by the disruption of the pandemic, may be harmed the most. Teenagers in cold homes, for example, can suffer four times greater impacts on mental health than adults(18).

Social impact of cold

“I live in the cold. My hands are freezing at the moment. Quite often my nose is cold like a dog’s. My kids are worried I will get pneumonia. My daughters won’t bring the kids around because my house is so cold. They worry about me too.” – 71-year-old former NHS worker (19)

Mental wellbeing and participation in normal life are closely linked – and badly affected by cold. Here again children are most vulnerable. For example, as Jessica Allen of the Institute of Health Equity warns: “It is humiliating for children to go to school in dirty clothes. They know their classmates can smell the damp and lack of washing. The self-consciousness is terrible.”

Dane Ralston of iOpt Assets has observed the way fuel poverty harms people’s social contacts. “People live like hermits, never go out, never see anyone.” Social isolation is not trivial – it is comparable to a significant smoking habit, in terms of the impact it has on health and life expectancy(20).

Lasting impacts, life chances

Children’s respiratory physician Professor Ian Sinha warns that the damage done to young lungs this winter will in some cases, lead to lifelong respiratory problems(21). Optimal lung development is impaired by cold, substandard or overcrowded housing, and hazards such as viruses, dust, mould and pollution.”

“Children always lose out in poverty. How you enter adulthood is absolutely crucial. Long term follow-up studies show half of people with COPD can trace this back to childhood circumstances. We predict the impact will be threefold this winter.(22)”

The impact on long-term respiratory health is just one of the many ways that poor housing in childhood feeds into a narrower life, poorer health and shorter life expectancy in adulthood.

Without a warm, quiet place to do their homework, children fall behind at school(23). Without clean clothes, children may opt not to go to school where they could face bullying and isolation.

The NEA and the Institute of Health Equity warn that children’s development will be “blighted with toxic stress that will affect brain development”.

“When we add in factors such as cutting back on food to pay the gas bills, and the mental and educational impact of cold houses, the picture is bleaker still.(24)”

The role of construction

The medical profession is aware that the way homes are constructed influences health, life chances – and life itself. Bad housing quality has been described as a “key component” in the doubled risk of infant death in deprived households. The Royal College of Paediatricians has said it is “highly likely that… poor housing conditions are in part responsible for the stark social gradient of childhood disease observed in the UK.(25)”

BRE has estimated that excess cold is the costliest of all the hazards in the Housing Health and Safety Rating System. In 2021 they said homes with ‘excess cold’ led to £857 million of direct NHS expenditure per year in England alone. This is just a fraction of the total cost to society. BRE estimates that lost education and employment opportunities adds another £11 of social harm for each £1 of NHS costs. For cold homes, this represents an annual drain on the nation equivalent to around £11.3bn(26).

As perhaps twice as many homes are likely to be hazardously cold this year, these costs can only be expected to rise.

Can better homes help?

It’s quite warm here in the winter without putting the heating on.” – Tenant of a passive house housing association home(27)

“We lived without the heating working just before Christmas; it needed a repair but we turned them away, and said ‘leave us for Christmas, we don’t need it doing now’; we were more than comfortable. It was amazingly windy cold and wet outside. Any other house you couldn’t have done that, but we didn’t miss it - we didn’t even notice.

“I think you could take the heating from this house and live without it.” – Tenants in a passive social home in Wales (28)

We saw in part 1 of this article that the risk of being in ‘fuel stress’ in one of our worst homes this winter is around five times higher than in a good home. We saw how cold – and damp – many people’s homes become, even when they do use some heating. By contrast, in a high-performing home, when precious money is spent on heat, that heat is retained.

In probably the most energy efficient buildings of all, passive houses, it costs just a tenth of what it might cost to heat a typical home – and a fifth of what it costs to heat a typical UK new build. In Ireland, research a few years ago showed that occupants of passive social homes spent relatively little – around two per cent - of their income on heating and hot water, even when on social welfare(29).

Some occupants find they don’t actually need the heating on at all(30). Exeter City Living has reported that in its 100 passive dwellings “60 per cent of the tenants haven’t had to switch on their heating(31).” People in a passive house who don’t have any money to spare for heating are therefore going to be far, far less cold than someone in a less efficient dwelling.

Calculations by the Passivhaus Trust investigating the impact of turning off the heating in cold winter weather, showed an unheated passive house would drop from 20 only to 19 C after one day, perhaps cooling down to about 16 C after being unheated for a week. A typical new build home – never mind an older one – might cool down to 14 by the end of day one, and by the end of the week, to more like 8 C(32).

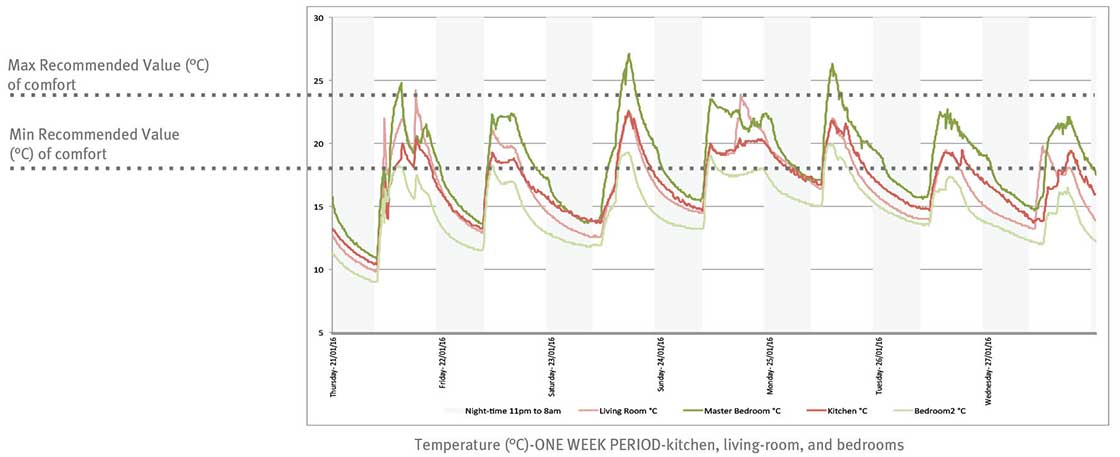

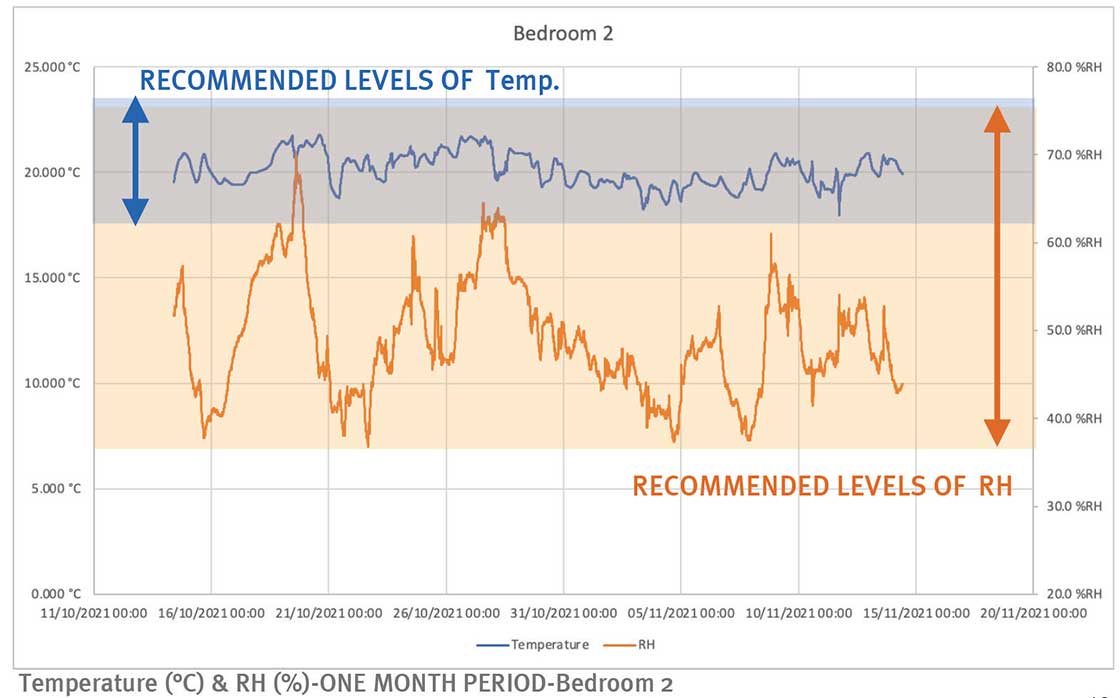

The rate of heat loss in a poorly insulated dwelling is vividly illustrated in a home monitored by John Gilbert Architects.

The home was a draughty sandstone tenement, occupied by an elderly man who was at home most of the time. Although some internal wall insulation had been installed, it did not appear to be performing well.

Every morning the occupant heated the flat to 20 C or more. But as soon as the heating was turned off, temperatures fell precipitously, down to between 12 and 15 C by next morning. Relative humidity was high, and in the bedroom, carbon dioxide levels were very high too – showing that despite the draughts, in the bedroom there was far too little fresh air.

John Gilbert Architects also monitored a social home built to the passive house standard. It too was occupied most of the time, this time by a pensioner couple. Here the temperature fluctuations were small – generally just one or two degrees. Throughout the flat, temperature, humidity and indoor air quality levels remained within recommended values.

What could high quality construction and retrofit achieve?

“My baby daughter had patches on her lung ... You could hear the raspiness in her cough, and a constantly runny nose. She doesn’t suffer from that anymore — since we’ve been here, she doesn’t cough in the night.” – Occupant of a passive house retrofit(33)

People who have moved into homes built to passive house or retrofitted to Enerphit standard have reported that their health – and the health of their families – noticeably improves.

As with physical health, so with mental and social well-being. Affordable warmth makes a big difference to people’s lives and relationships. People can sit together, or take themselves off for privacy, as they need to. Research has found that “improvements to energy efficiency are often associated with significant improvements in mental well-being... [people] report immediate impacts on their mood and quality of life(34).”

Debt charities, medical professionals, climate activists – all are repeating the call to improve people’s homes at vastly accelerated rates, so that the disaster that is befalling Irish and British citizens this winter is never so punishing again.

The construction industry might legitimately see itself as a branch of the health service. After all, as Sir Michael Marmot asks, “What good does it do to treat people, and send them back to the conditions that made them sick?(35)”

For more information about the impact of housing quality on health, and the health and social benefits of high-performance buildings, see the forthcoming reviews from the Passivhaus Trust, by the same author.

References

(2)Connecting Homes for Health, National Energy Action

(4)Housing and Health Inequalities in London, Institute of Health Equity

(5) Report on the health benefits of Passivhaus, forthcoming from the Passivhaus Trust

(7)Royal college of paediatricians and Child Health, Inside Story

(9)Better at Home End of programme report 2016-2018 National Energy Action and MacMillan Fund

(12)Northern Ireland Carers Association speaking at National Energy Action event, September 2022

(14)Data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007, a survey of 7,400 people

(17)Rocio Concha of Which? Talking at a Citizen’s Advice event in October 2022

(18)Institute of Health Equity

(19)Daily Mirror, January 2022

(20)References via Campaign to End Loneliness

(21)Launch of Institute of Health Equity report, September 2022

(24)Professor Ian Sinha and Professor Sir Michael Marmot, BMJ, September 2022

(25)RCPCH, The Inside Story, 2019

(26)BRE report “The Cost of Poor Housing in England” 2021

(27)Passivhaus goes Social, Passivhaus Trust

(28)Occupant interview, Bere architects

(30)UK Passivhaus and the energy performance gap, Rachel Mitchell, Sukumar Natarajan, 2020

(31)Eco-homes become hot property in UK's zero-carbon ‘paradigm shift’ Guardian March 2021

(33)Passive House Plus, issue 22

(35)The Health Gap, International Journal of Epidemiology, Sir Michael Marmot, 2015