- Insight

- Posted

Cold Truths: Part 1

While most people will feel the squeeze as a consequence of the energy crisis, for vulnerable people spikes in energy prices may be a matter of life and death. In a two-part mini-series of articles in this issue, Kate de Selincourt peers into the void to see how vulnerable people may respond to high energy prices, and what the impact will be for their living conditions and their health.

This article was originally published in issue 43 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Households across the UK and Ireland are in for a cold, and frighteningly expensive winter. Prices for gas, electricity and heating fuel have shot up. In the UK, government interventions have capped some of the rises till April, but costs are still double what they were a year ago. In Ireland, no such cap currently exists.

As a result health specialists are in no doubt that people will die. Vulnerable adults will lose their lives because their homes are cold – and damp(1). But so also will babies and young children. A respiratory consultant told the press he had “no doubt” that cold homes would cost children’s lives this winter, adding that many more will suffer harm to their health and their life chances, marking them for the rest of their lives (2).

The cost of energy rose as economic activity increased, after Covid restrictions were eased. Then at the start of 2022 Russia, one of the world’s main oil and gas producers, invaded Ukraine. Prices leapt again.

Someone heating an average UK home to a reasonable temperature will have to find double the money – an extra £1,200 on average – this year (3). In Ireland price rises are at least as brutal. A large percentage of Irish households depend on oil or LPG, which is expensive. A typical €2,000 annual bill in 2021 had reportedly risen to around €4,000 by September 2022, and while prices have since softened, they could rise further(4).

But people don’t have the money. As a consultant working with social landlords put it: “There is an absolute catastrophe coming down the line this winter.(5)”

The majority of households expect to use less heating this winter. An Office for National Statistics survey in spring 2022 found ‘about four in 10 British households were already finding it difficult to pay for gas and electricity’(6). Many homes will be dangerously cold.

The pain will not fall equally. People on low incomes – already at higher risk of ill-health – will be least able to keep their homes warm and healthy. People in larger or less efficient homes, who are at home more than average, where someone needs warmth for health reasons, or where there are more children, will face even bigger cost rises.

Gareth McNab of charity Christians Against Poverty describes a household they have helped. There are several children, and one of the adults has brittle bone disease, needing warmth to stay alive. “Their bill is likely to be £7,500”.

Energy costs are not rising equally

In the UK about 85 per cent of households pay energy prices controlled by a ‘price cap’ set centrally. In September, UK government intervention capped the average ‘dual bill’ (gas plus electricity) at £2,500 – more than twice what it was last winter.

While price caps are applied to electricity and gas in the UK, price caps don’t cover heating fuels such as oil and LPG used by offgas- grid properties in much of rural Britain, as well as Ireland. Off-gas users also have to find a lump sum of money, in advance, to fill the tank – and many are unable.

Households served by communal heating are not protected either. Prices for heat have risen in line with the soaring world gas price.

In October, Alex Hern, technology editor with The Guardian tweeted: “My communal heating provider has finally put up our (uncapped) prices. By 1,076%... gonna be a chilly winter(7)”

The UK government says it plans to act on this issue (8) but with UK politics in turmoil there may be some wait. There is a similar situation with communal heating in Ireland.

People using energy prepayment meters are also hard hit. Prepayment customers need to pay more each week over winter because they can’t spread seasonal costs. If they can’t feed the meter they lose their supply. This may even lose them food in their fridge and freezer, as well as the immediate distress and danger.

On top of this, many prepayment meters are fitted by energy companies to recover energy debt. The company may then take 25 per cent, 90 per cent or even 100 per cent of the money paid into the meter, towards the debt. The customer needs to find more money again, to receive any energy at all (9).

The special horror of prepayment meters

Although some households opt voluntarily for a prepayment meter to control their energy spending, many more have them imposed, usually because they are in debt to the energy company. (Citizens Advice is asking for a temporary ban on this practice over the winter).

Well over 4 million UK households already have these meters. As energy debt is rising, thousands more are installed each month, and the rate of installation is increasing, causing widespread concern(10).

Smart meters can be remotely switched to prepayment(11). Companies have also reportedly broken into homes to physically fit them(12).

The level of debt recovery enforced on prepayment customers has been described as ‘callous’ and ‘horrific’. For example, the British Gas website (accessed 10th October) tells customers: “If you don’t top up enough to pay us back, don’t worry, we won’t leave you without any gas or electricity. When you top up, we’ll take 90 per cent to pay towards your debt and leave 10% for your gas.”

“For example, if your agreed weekly amount is £10 and you top up £10, we’ll put £9 towards your debt and leave you £1 for gas. You’ll still owe us £1, which we’ll take next time you top up that week.”

Such punitive levels of debt recovery mean people often don’t bother to top up at all(13). This is euphemistically described as “self-disconnection”. The consequences are described below.

Not all homes are equal

People in less efficient home face far worse difficulties than those in better-constructed buildings. Dane Ralston of iOpt Assets, who monitors indoor environmental conditions for social landlords, describes one such home: “It was costing £400 a month to heat her home – basically just heating the main bedroom where her child more or less lived,” he said. “There was a bit of heat in the other bedroom – it sat at around 16 – and none in the living room. The house was desperately inefficient.”

Energy ratings such as the UK’s EPC and Ireland’s BER are only a rough indicator of building performance. However more than half of homes in the UK, and almost half of those in Ireland, have an energy rating of D or below, which means they are likely to be very expensive to heat. The coldest homes tend to be pre-1990s – these are where the D, E, F and G-rated homes are mostly found.

Although recently constructed homes generally score C or above, in reality, the energy performance is far from guaranteed, because of the performance gap. Even homes that ought to be warm are not, because failures in airtightness, and badly installed or missing insulation, can add 60 per cent or more to the intended heat demand(14).

While energy ratings are not a great guide to individual performance, the underlying calculations do give an idea of the difference between the best and worst. If we compare a notional EPC/BER B with a notional G, we can see just how much it matters.

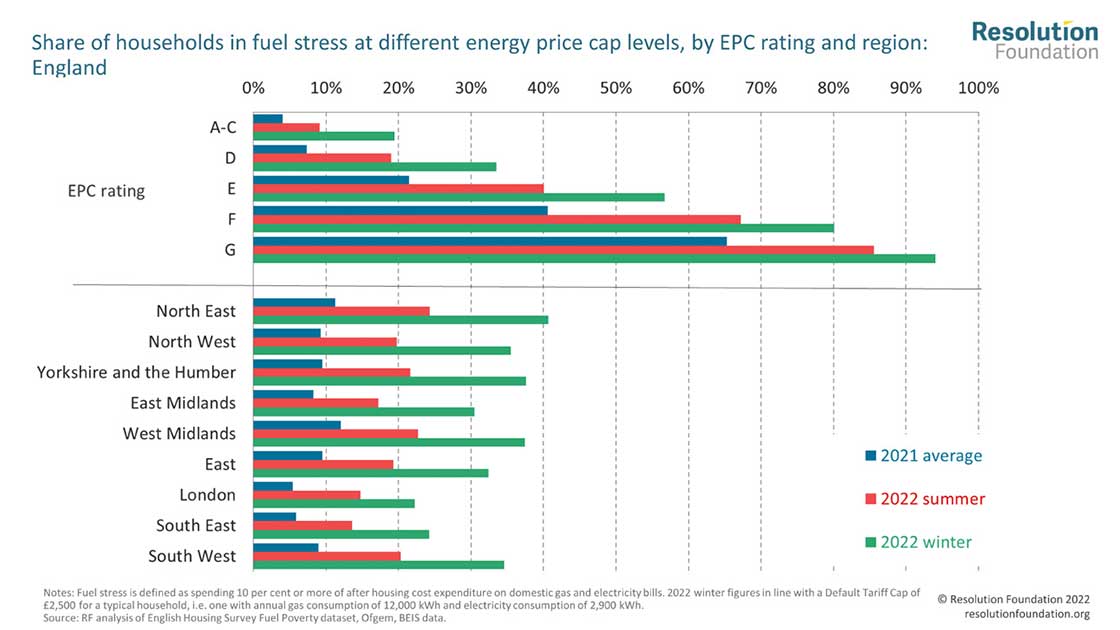

According to calculations by the Resolution Foundation, in England, at winter 2022 prices, someone even in one of the most efficient homes – rated EPC A-C - has a 20 per cent chance of being in fuel stress(15). Households living in a G-rated home, by contrast, are basically certain to be in fuel stress, unless they are in the wealthiest 5 per cent of the population. (See Figure 1).

Caption: The risk of being in ‘fuel stress’ in one of our worst homes this winter is around five times higher than in a good home. Graph: Resolution Foundation (16)

This winter’s crises – the early indicators

Even before the current crisis, people were ringing the alarm bells about energy affordability. “In Scotland, we have people facing £1,500 annual fuel bills, when their annual income is £10,000. This is extreme fuel poverty,” Duncan Smith, sustainability & energy manager at River Clyde Homes, pointed out in spring 2022 (17).

The dramatic price increases this winter are occurring along with rising living and housing costs. Many households are without a financial cushion of any kind – increasing numbers are in debt. Some were resorting to gambling, or using high-cost short term loans, even before the weather turned cold, or Christmas loomed (18).

Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) reported this summer that energy poverty was at the highest ever recorded rate, with an estimated 29 per cent of households considered to be in energy poverty (19). The estimate is based on energy prices in April, plus a further 25 per cent rise anticipated this winter. One report suggested that households with an income of less than €115,000 would be defined as being in energy poverty. By the calculations of fuel poverty charity National Energy Action, around four million households in the UK were in fuel poverty last year.

This year, it is almost seven million. Calls for help to UK debt crisis charity Christians Against Poverty rose by around 40 per cent from January to October, and the nature of them has changed. “They are more concerning,” said the charity’s Gareth McNab. “By the first call people are already in crisis, urgently in need of food and fuel vouchers. Demand for fuel vouchers this summer was triple what it was a year ago – already at levels we associate with winter.(20)”

Worse, for an increasing proportion of their clients, there is no way to make their outgoings match their income. “There just isn’t enough money coming in to meet the costs of what they need.”

People on the lowest incomes and those in the least efficient homes are the hardest hit. If someone in the top income decile in one of our worst dwellings needs 10 per cent of their extremely comfortable income to pay for energy, how will a low-income household cope? As National Energy Action charity head Adam Scorer said: “For some households 30, 40, 50 per cent of their income would have to be spent on energy, to get decent level of services like heat, cooking, washing, hot water.

So, the alternatives are impossible debt, or dangerous privation.(21)”

Desperate measures behind closed doors

“A crisis is when coping mechanisms fail, leaving despair & hopelessness,” says Adam Scorer. “Millions are there already.” Rationing energy use is nothing new – Scorer relays a familiar pattern, with prepayment customers typically topping up a small amount at the beginning of the week, then running out after three or four days (22).

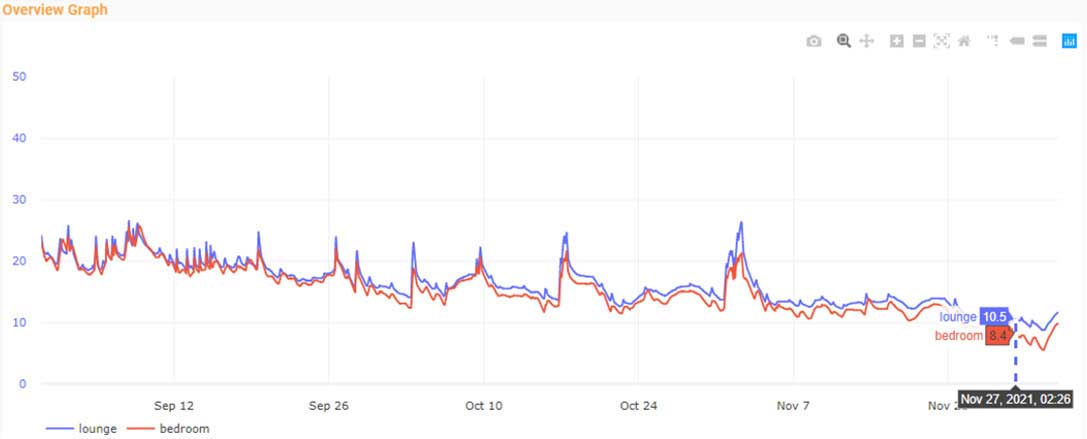

This pattern was illustrated in monitoring information recorded in a flat by iOpt on behalf of a social landlord. Regular spikes of warmth showed the tenant heating for a day or so after pay day, but as autumn progressed her home steadily lost temperature, sitting at a chilly 15 degrees or below. Then the spikes stopped, and the temperature just fell, down to a dangerously cold 8-10 degrees by November. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2: Temperatures in a flat where heating was used for one or two days each week until early November, at which point no heating was used at all. Image courtesy of iOpt Assets

It turned out the occupant had lost her job. In this instance, the landlord was alerted to the danger and, fortunately, was able to find some support for the occupant. This wasn’t the coldest home iOpt had seen. “Last winter we were seeing some properties sitting at 4,5 or 6 C for weeks on end,” Dane Ralston told Passive House Plus.

This winter many more people are in this situation. “People are on the edge of not being able to pay their bills,” says Ralston. “So many are close to that point, and will be tipped into not heating this winter.” Most households are being careful with energy this winter. Many cannot afford to keep as warm as they would like. But for a shocking number, fuel poverty doesn’t just mean struggling to pay bills, it means having no heating whatsoever – and sometimes, no energy at all.

For people on prepayment meters, and indeed, any householder terrified of energy costs, the reality can be not only no heating, but no way to cook, bathe or wash laundry. It can mean no light, no fridge, no internet, no TV.

UK regulatory body Ofgem admitted last year that even before the pandemic, self-disconnection was occurring at unacceptable levels, with perhaps one in six prepayment customers being without gas, electricity or both at least once a year. “The level of individual consumer harm experienced can be significant,” they said (24). The situation this winter is far worse.

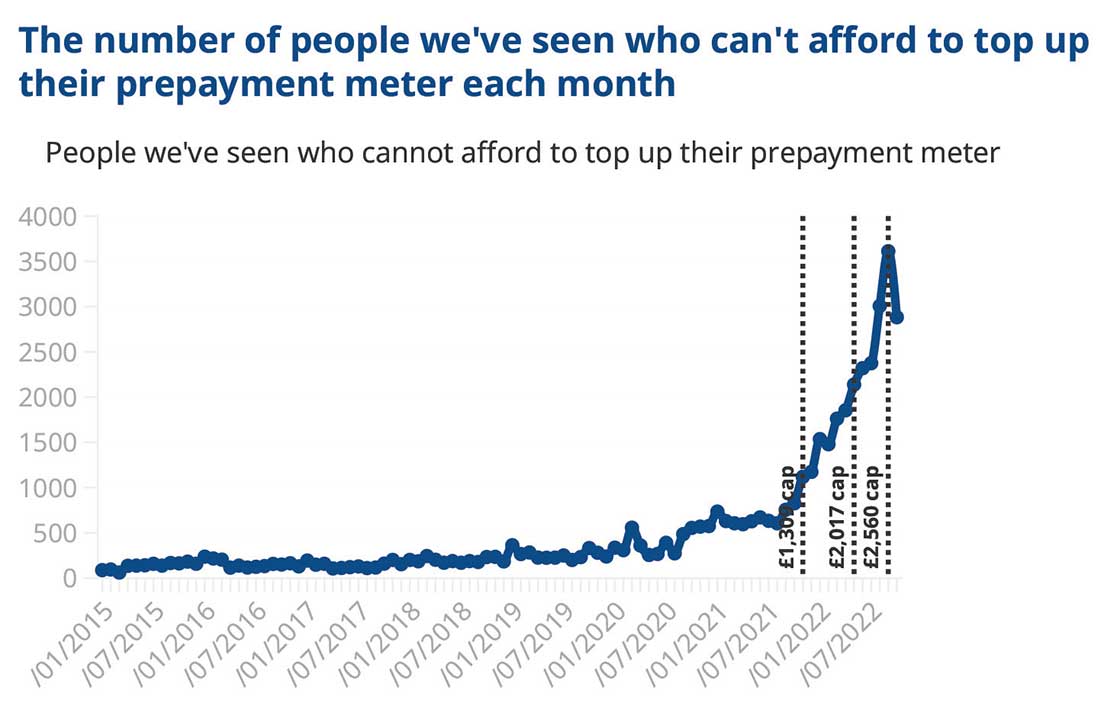

Even before the October price rise, self-disconnections began to “skyrocket”.(25)(26) Citizen’s Advice “had more people contact us about not being able to top up their meter in July than in January,” an almost seven-fold increase vs the previous summer. By October, calls for help were at record numbers – described as “absolutely staggering” by the charity (see Figure 3)(27).

Figure 3: Data for England and Wales, from local Citizens Advice offices and the Citizens Advice consumer service.

Adam Scorer described some of the coping mechanisms National Energy Action had heard about to an online event in October: “Borrowing/gambling/pawning. Sending kids to friends/family. No bathing/ showering. Cold food only. No heat, or one room for an hour. Foraging for wet wood. Barbecues indoors. Keeping kids off school because the parents can’t wash the children’s clothes...”

Gareth McNab said his charity had had calls from parents whose children’s feet were turning blue with cold. “They were so terrified they could not find a way through, they had considered having the children looked after in care.”

Unprecedented low temperatures

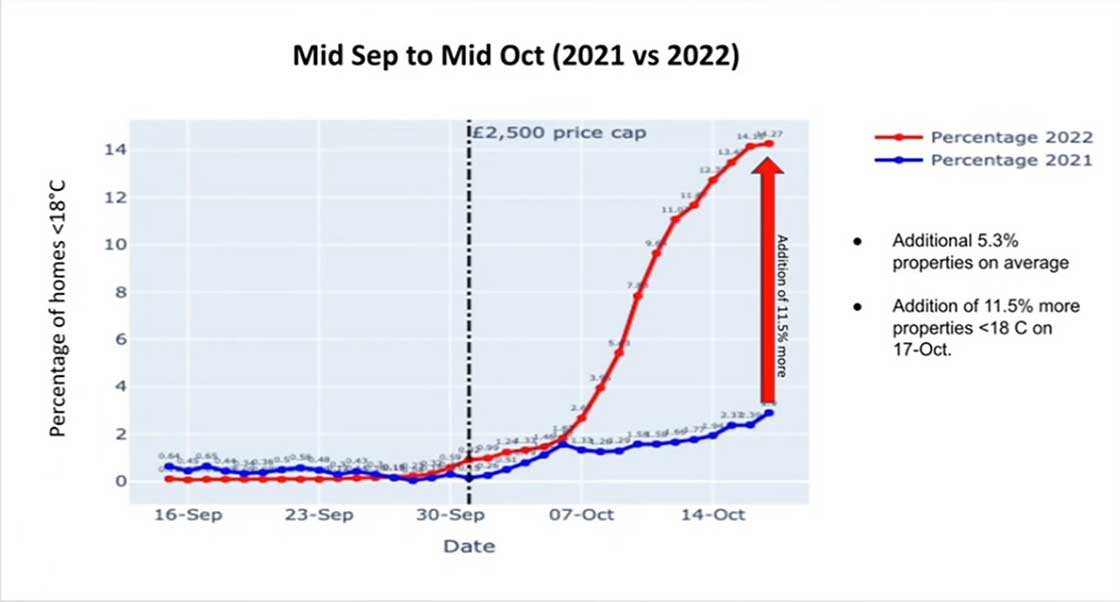

Smart thermostat and energy software company Switchee has records of indoor conditions in a large number of social homes over the past three years. Their data from 2019-2021 shows a steady rise (of about six per cent per year) of the proportion of households spending prolonged periods in winter with their dwellings below the recommended 18 degrees (28).

However the figures for autumn 2022 are unprecedented – as soon as the weather began to cool, the number of homes falling below 18 C skyrocketed. This is in sharp contrast to previous Octobers (with similar weather) when the percentage of cold homes crept up only gradually. (See Figure 4).

Figure 4: Slide from Switchee’s Winter 101 webinar series, percentage of homes at below 18C from 2021 to 2022

The contrast between last year and this year echoes the experience of debt and fuel poverty helplines – unprecedented levels of hardship, rising at unprecedented speeds.

Switchee also report that people have lowered their thermostat temperatures. As soon as the price cap hit, typical target temperatures dropped from around 18 to around 15.

And heating is on “about half an hour less, less than 2 hours a day now.”

Humidity and indoor pollution

A common strategy for people struggling to afford heating – frequently suggested on social media – is to heat just one room, rather than the whole home. And advice on ‘draughtproofing’ also abounds. Even if extra measures aren’t taken, the natural inclination is to shut off ventilation, because (in homes without heat recovery ventilation) fresh air in winter means cold air.

The net effect of this is to increase relative humidity, especially in unheated rooms. This in turn can lead to condensation and mould.

Glasgow-based John Gilbert Architects have monitored the homes of people in fuel poverty, to help social landlords plan their retrofit strategies. One such flat was occupied by two pensioners, one of them with chronic respiratory disease, needing oxygen to breathe overnight.

As Barbara Lantschner of John Gilbert Architects explains, they only heated the living room and kitchen, to save energy. The bedrooms were therefore constantly cold. On some occasions the bedrooms fell below 14 C – well below recommended values of comfort, and potentially dangerous to someone with a lung condition. Humidity in the bedrooms was relatively high (often around 70 per cent, i.e., above recommendations), and the rooms showed signs of mould growth and condensation. CO2 levels were also high, suggesting the home was under-ventilated.

In another flat monitored by John Gilbert Architects, the occupants kept just one room above 18 degrees – most likely with a stand-alone heater. That room showed regular spikes in humidity and CO2 – at 80 per cent and 2,000 ppm respectively, again indicating underventilation. This flat too had condensation and mould.

Dane Ralston at iOpt also sees dwellings at around 13 C where “the relative humidity is in the high 80s. This means the condensation and mould risk is extremely high.”

It is not just the lowest-income households who are likely to suffer underventilation.

Even without the pressures of 2022 fuel prices, the installed ventilation in UK homes is often inadequate (29) – and this year people are going to use it less.

As Simon Jones, head of air quality at environment analytics company Ambisense put it: “The instinct to shut things down and seal things up [is] very understandable given the cost of living crisis. Couple this with heating our buildings less often, and you have significantly increased the likelihood for condensation and mould.(30)”

People on the lowest incomes are least likely to be able to use tumble driers or outdoor lines (31). Drying laundry indoors raises humidity, potentially doubling the levels of mould spores. The colder the home, the worse this gets.

Woodburning and other air pollution

When the price of grid energy rises, people turn to polluting alternatives. Indoor fuel burning, be it in a fireplace, stove or free-standing heater, directly pollutes the indoor air (32). Smoke from wood, coal, peat or turf burning pollutes neighbouring homes too. Although particulate pollution is associated with vehicles, UK government figures show that domestic solid fuel contributes around three times as much particulate pollution to the air as road traffic.

Other pollution risks include cooking indoors on camping stoves, or even, horrifyingly, indoor barbecues (as mentioned above), likely to emit both carbon monoxide (a neurotoxin) and nitrogen dioxide (a lung irritant).

The implications of cold, underventilation and poor indoor air quality on occupant health are explored in part two. Click here to read on.

References

(1)NICE guidance Excess winter deaths and illness and the health risks associated with cold homes

(5)Dane Ralston, iOpt, pers comm

(6)Financial Times, April 2022

(7)Tweeted by Alex Hern, Technology Editor of the Guardian Newspaper, in October 2022

(8)Energy Minister Lord Callanan speaking at a National Energy Action event, September 2022

(10)Observer 23.10.2022, Financial Times, 24.10.2022

(11)Energy firms remotely swap homes to prepay meters BBC News November 2022

(16)Stressed Out, Resolution Foundation, April 2022

(18)Adam Scorer, NEA, speaking at an online event October 2022

(19)https://www.esri.ie/news/energy-poverty-at-highest-recorded-rate Irish Times September 2022

(20)Gareth Mcnab talking in September at event run by National Energy Action

(21)Adam Scorer, NEA, speaking at an online event October 2022

(22)Christians Against Poverty report, 2019

(24)Ofgem Inquiry into Self-disconnection and self-rationing, final impact assessment

(26)Dr Elizabeth Blakelock at Citizens Advice online event

(27)Citizen’s Advice chief analyst Tom MacInnes at Citizens Advice online event

(28)Information shared at Switchee online seminar, October 2022

(30)How high fuel bills can worsen air pollution in our homes Guardian October 2022

(32)Wood burners triple harmful indoor air pollution, study finds. Guardian December 2020