- Case Studies

- Posted

Pre Form Precision

The desire for better insulated, more environmentally friendly homes is driving ever more Irish self-builders to investigate alternatives to traditional block building. Jason Walsh visited a contemporary style factory-built timber frame house built in County Waterford in 2005.

Set in six acres (24.37 hectares) of land near Woodstown in County Waterford is the house of Joan Dalton and family. Designed by David Smyth of David Smyth Architects in Waterford town, the residence is intended to not only be a comfortable and aesthetically pleasing home, but to also be an environmentally sensitive building in both its construction and performance.

Eschewing traditional building techniques, the house was manufactured in a factory in Mullingar, before being transported to County Waterford and assembled on-site.

When it came to building their own home, Joan Dalton and her husband Darragh knew from the outset that they wanted an architect-designed house but did not initially plan on choosing a factory-built dwelling: "We originally considered a post and lintel straw bale house," says Dalton.

However, Dalton did know from past experience that she would prefer to not have a traditional Irish blockwork house: "I grew up in the US and have always had a sense that wooden houses are somehow sweeter," she says.

Dalton approached Waterford-based architect David Smyth to design the house: "It started off as a green, eco-house with energy as the main component [of the strategy]," says Smyth.

For Smyth, a major bonus was the system's flexibility and the manufacturer's ability to accommodate his designs: "I suggested they take a look at the Griffner Coillte system. The house was designed without a Griffner Coillte system in mind but when I came to them I didn't have to change too much."

Architect David Smyth designed an overhang to meet the Dalton's requirements to create an outdoor relaxation area that could be used even on rainy days

Architect David Smyth designed an overhang to meet the Dalton's requirements to create an outdoor relaxation area that could be used even on rainy days

Machines for living

Lurking in the dark recesses of the Irish psyche – and presumably in the imaginations of various constriction industry lobbyists – is the idea that prefabrication somehow equals shoddiness.

Indeed, the term 'prefab' itself conjures up images of temporary structures: 'mobile' school huts provided by poorly-funded education authorities and the dreary tin houses and Nissen huts with less decorative value than a Calvinist Bible hall built in Britain and the North of Ireland to deal with the post-war housing shortage.

While it is the case that, in the UK and Ireland at least, much prefabricated (or factory-built, as its proponents prefer) building has been done for purely utilitarian reasons, there are significant counter-examples, particularly in continental Europe.

Today's manufactured dwellings, particularly those modelled on German and Scandinavian successes, offer several clear benefits over traditional blockwork houses.

Firstly, there are advantages in terms of quality control. For a start, traditional building is simply unpredictable: anything can happen on site and there are, as Donald Rumsfeld might say, many "known unknowns" such as weather conditions and uneven skill levels, all of which can wreak havoc on even the most meticulously planned construction schedule, not to mention the final quality of the building.

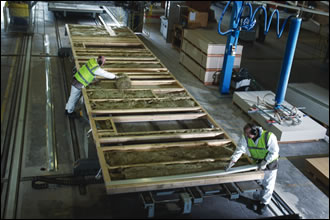

Griffner Coillte's production approach involves the walls being built and fitted with insulation in a controlled factory environment, avoiding the possibility of insite mistakes undermining thermal performance

Griffner Coillte's production approach involves the walls being built and fitted with insulation in a controlled factory environment, avoiding the possibility of insite mistakes undermining thermal performance

Secondly, factory-built houses can be designed to meet energy efficiency targets that traditional building would struggle to match.

Thirdly, in stark contrast with traditional building methods, once manufactured the components can be assembled on site with lightning speed, often taking mere weeks to build.

Finally, in an era of boutique consumerism, prefabrication offers a fringe benefit in that it dramatically lowers the construction costs of unique one-off buildings. For the first time in history, unique houses are, if not actually inexpensive, at least potentially affordable.

In Britain the dearth of affordable housing in the capital has led deputy prime minister John Prescott to seriously investigate the possibility of large scale prefab housing in the London orbital area. That the houses' aesthetic will likely be inspired by a sort of soft modernism is coincidental – it's the building process itself that owes most to the dreams of the modernists, not their exterior style.

It's worth noting that the growth in factory-built dwellings is not the work of some lunatic fringe. Such renowned architects as Frank Gehry and Matteo Thun – who designed O Sole Mio, a factor-built house built by Griffner Coillte’s Austrian partner Griffner Haus – have turned their attention to prefab housing in recent years and the trend is growing internationally.

Even in the United States, where the oversized traditional "McMansion" is the typically desired home and prefab has usually been associated with trailer parks, the combination of high quality engineering and architecture along with dramatically reduced costs is driving interest in manufactured housing. In Japan, meanwhile, all high-end homes are prefabricated as a result of the desire for precision cutting and quality control.

It's not just cost, convenience or even quality that is driving the mini-boom, though – sustainability is also an issue. Take the German example: traditional German building is considered, like that in Ireland, to be "fortress-like" resulting in housing that is expensive, slow to build and environmentally wasteful. Despite this – or perhaps because of it – interest in manufactured housing has greatly increased. In a recent interview with the German international broadcaster Deutsche Welle, Christoph Windschief, spokesperson for the German Prefabricated Housing Association (BDF) said: "Prefab houses attract particular buyers – people interested in ecologically sound living."

The Matteo Thun designed O Sole Mio

The Matteo Thun designed O Sole Mio

New Woodstown

In the case of Joan Dalton's home in County Waterford this is certainly the case. Dalton knew from the outset that she wanted a low-impact, high-efficiency home.

According to David Smyth, interest in more sustainable living is growing among Irish home-buyers: "I think there's an increased awareness of energy efficiency and insulation," he says.

When it came to designing the house, simple measures were taken to negate the need for high-tech energy solutions: "With the design, the first thing was catching sunlight. It maximises passive solar gain – the site allows for very good positioning," says Smyth.

He also notes the building's inherently low-impact nature: "It's a house that, if it had to be pulled down and destroyed, it wouldn't leave a lot of material that would damage the environment."

The house's total floor size is is 2,800 sq. ft. (260.13 m2) and is one storey high. "We could only build a single storey because of planning restrictions," says Dalton.

For heating the house uses a geothermal heat pump-based system which feeds into underfloor heating: "Geothermal seemed the most comprehensive technology and it chimed well with underfloor heating," says Dalton. "We also have planning permission for solar but with geothermal you've already got all of the heating you need."

The Kazuhiko Namba designed Muji infill house showcases sustainable pre-engineered solutions

The Kazuhiko Namba designed Muji infill house showcases sustainable pre-engineered solutions

The desire to move to a sustainable energy source is not uncommon in Ireland today, particularly in light of the availability of generous grant aid from Sustainable Energy Ireland (SEI), but Dalton's motivation was not solely economic, as witnessed by the fact that the house did not receive funding from SEI, its construction predating the grant scheme by some months.

"The rising price is oil was a factor, of course," says Dalton, "but we wanted to reduce our dependency [on non-renewable sources].

Nevertheless, the economic benefit is a clear one. According to Dalton, the annual electricity bill is in the region of €1,300, which includes not only the heat pump but all electrical devices used in the house.

High quality timber is utilised extensively both internally and externally and external cladding is incorporated into the factory prefabrication process to minimise the amount of on site work post erection

High quality timber is utilised extensively both internally and externally and external cladding is incorporated into the factory prefabrication process to minimise the amount of on site work post erection

The heat pump system is an NIBE Fighter 1110, a Swedish design, which has recently been retired by NIBE, its successor being the 1120. The 1110 is an 11kw heat pump, supplied by a ground source.

Paul O'Donnell, from Unipipe Ireland, supplier of the heat pump says: "[With the 1110] Average efficiency is high. It only generates heat as needed.

"If it's running on an average day it has seven degrees coming in [from the ground source] and 35 degrees going out through the floor [and] it has a COP efficiency of 5.71:1."

O'Donnell also explains that the underfloor heating contributes to the efficiency of the system: "If it was running with radiators at high temperature, the COP would be 4:1."

O'Donnell's predictions for the systems performance are close to Dalton's actual experience: "I'd expect an average running cost of €900 – €1100 for a 3,000 sq. ft. [278.7 m2] house," he says.

In addition to geothermal heating, the house also adheres to sound design principles: "It's a slightly passive solar design," says Dalton, referring to the house's southern orientation and maximisation of glazing to the south and its minimisation to the north.

Mineral wool fibre, specifically rock wool, insulation is used throughout the dwelling.

The rear of the house addresses an outdoor relaxation area. According to David Smyth this development came about as a result of the design process itself: "I usually ask people to write down eight or ten words describing what they want. Most people come back with the same things, but Darragh said: 'It rains a lot in Ireland – wouldn't it be nice to be able to sit outside in the rain and stay dry?' As a result we designed the overhang."

Situated at the rear of the house and shielded from the elements by the overhanging roof and two extruded blocks containing the living area and bedrooms, the result is a pleasant secluded area with a higher than average median temperature.

This backs on the rear of the entrance atrium which Dalton describes thusly: "The atrium area is a heat sink which tops up the piped water and brings the outdoors and indoors together."

The house's total floor size is 2,800 sq ft and is one storey high, essentially taking the form of a streamlined and updated traditional bungalow. "We could only build a single storey because of planning restrictions," says Dalton

The house's total floor size is 2,800 sq ft and is one storey high, essentially taking the form of a streamlined and updated traditional bungalow. "We could only build a single storey because of planning restrictions," says Dalton

Built to order

Despite the house essentially taking the form of a streamlined and updated traditional bungalow, as noted above the construction methods used in its building were far from commonplace.

The factory-led construction technique used by Griffner Coillte is virtually unique in Ireland and offers several key benefits over blockwork construction. For a start, no bricks, blocks or wet trades are involved.

David Smyth points out that the house is fundamentally better-built than many traditional dwellings: "There aren't any cold bridges and the window system they use has a very good U-value," he says.

The assembly process is rapid: "The walls arrived complete, on trucks," says Dalton, noting that she had planned to be there for construction but by the time she had arrived, the walls were already in place.

"There were six months total construction [including engineering] with a long design and planning period," she says.

Griffner Coillte positions itself as a market leader in Ireland: "It's a closed-wall construction system," explains the firm's CEO Bill Stanley. "The most significant thing [about it] is the construction process [which] takes place off site in a controlled factory environment."

Manufacturing-inspired factory construction techniques ultimately result in Griffner Coillte's ability to offer better inherent energy efficiency than traditional builders, as Stanley explains: "It allows you to precision engineer and better control quality.

"You get an air-tight product: every window [for example] goes into an opening specifically designed for it – down to millimetre tolerances," he says.

Stanley points out that the company's houses are not the same as traditional timber frame buildings: "You don't have a lot of work to do on site and the technique allows you to achieve better U-values.

"We have a breathable wall system [so] you don't risk a build-up of moisture in the walls. Externally, we have a very thick but diffusible board," he says. "The internal timberwork is not treated with chemicals – it's not necessary because it's kept dry."

Even the simple fact of factory production methods results in higher quality workmanship: "When the roof, wall and floor elements go out on site they're designed to meet. They're also well-insulated and have a cavity for utilities," he says.

Stanley points out that Griffner Coillte is willing to stand by its claims of superior performance: "We had studies done by the Fraunhofer Institute [and] we've recently completed and launched our first dedicated show home in Fermoy, County Cork.

"We're also using it for testing the product – we've done air-tightness testing and a preliminary DEAP analysis. We plan to do some acoustic testing."

According to Stanley, performance is everything in the self-build market, composed as it is of knowledgeable and interested people driven by a focus on energy use: "It's not cheap and we don't make any apologies," he says.

"When I first got involved with Griffner Coillte, people were bowled over by our U-values; these days they're not but it's important to remember that they are elemental U-values," he says.

The last word, of course, should go to the owner-occupier. Joan Dalton says that not only is she satisfied with the house, she is genuinely enthused by it: "It's more than surpassed our expectations, coming from a brick-built, late 70s house."

Selected project team members / suppliers:

Architect: David Smyth Architects

House system: Griffner Coillte

Heat pump & underfloor heating: Unipipe Ireland

- Articles

- Case Studies

- Pre Form Precision

- Woodstown

- Waterford

- prefabricated

- prefab

- affordable housing

- passive solar gain

- heat pump

- Geothermal

- griffner coillte

Related items

-

Is shared equity a bridge too far?

-

It's a lovely house to live in now

It's a lovely house to live in now -

Is affordable housing a policy blind spot?

Is affordable housing a policy blind spot? -

Built Environment completes ‘mammoth’ MVHR installation

Built Environment completes ‘mammoth’ MVHR installation -

Is the O’Devaney Gardens deal social vandalism?

Is the O’Devaney Gardens deal social vandalism? -

Office-to-flat conversions “deeply worrying”

Office-to-flat conversions “deeply worrying” -

State-of-the-art heating test lab opens at GMIT

State-of-the-art heating test lab opens at GMIT -

Woodland wonder

Woodland wonder -

Phase one complete at UK’s largest passive scheme

Phase one complete at UK’s largest passive scheme -

Essex village becomes eco-pioneer with latest passive house scheme

Essex village becomes eco-pioneer with latest passive house scheme -

Scottish isle eco cottages need no central heating

Scottish isle eco cottages need no central heating -

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay