- Blogs

- Posted

ESG: a game changer for sustainable building?

With signs that the corporate world may be starting to move from greenwashing to genuinely grappling with sustainability via environmental, social and governance reporting (ESG), will this create opportunities for the widespread adoption of evidence-based sustainable building? Archie O’Donnell, Passive House Association of Ireland board member and environmental manager with i3PT, finds reasons for optimism.

This article was originally published in issue 40 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

The planet is currently on course for 4 C warming by 2100. COP26 made it clear that in order for us to meet a 2 C target – never mind 1.5 C – governments need to take the lead in realising a net zero world economy much sooner than 2050.

Buildings are a significant part of the problem, even before we consider the issue of the carbon embodied in constructing buildings. Emissions associated with heating and powering the built environment constituted roughly a quarter of Ireland’s total emissions in 2019 – including 15.8 per cent for the energy industries sector and 10.9 per cent for the residential sector.

But if we are to radically decarbonise these and all other sectors, we cannot solely rely on governments. Crucially, of the two hundred largest entities in the world economies, countries make up only 32 per cent of the list. One-hundred- and-fifty-seven of the top 200 economic entities by revenue are corporations. If climate change is to be tackled in a meaningful way, the private sector must take on its fair share of the heavy lifting.

In the past, when the private sector has made environmental improvements, it has tended to be government-led. In the construction industry, this has included incrementally adjusting our designs and specifications, to keep in step with the ever-tightening energy and carbon thresholds set by European directives and national building regulations, which are now being updated with increasing frequency.

For instance, the NZEB standard was applied in 2018/2019 with additional requirements added in 2021 and the next step change to Part L of the building regulations is due in 2023/2024.

The European Green Deal objective of driving the clean energy transition sets out to achieve the ambitious goal of carbon neutrality by 2050. The next recast of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive and Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) will see all new buildings moving to net zero by 2030, along with legally binding energy performance standards for private rental properties in 2025.

In Ireland, the 2021 Climate Action Plan’s decarbonisation pathway seeks to reduce emissions by 51 per cent by 2030 across all sectors. The plan targets reductions in built environment sector emissions from 7.9 megatonnes (Mt) to 4.5 Mt of CO2 equivalent by 2030. The plan includes an objective to bring 40 per cent of existing homes up to a B2 BER. Cost optimality studies are now being requested for the next iteration of Part L regulations for both dwellings and non-dwellings, indicating more onerous building regulations are due in 2023/2024.

But however fast-paced the speed of implementation of new regulatory standards and ever-tightening efficiency thresholds may be, these may be overtaken by an altogether larger and more effective force: that of the investment community and private equity.

This sector is channelling trillions of dollars of investment flows into ‘greener’ financial products: investments that have a less damaging impact, or in some cases, a positive benefit for the environment and human capital. This brings with it a whole new set of acronyms to add to our sustainability alphabet soup, the most prominent of which may be ESG.

ESG stands for environmental, social, and governance. The advent of ESG is leading to the uptake of toolkits and metrics for sustainability indicators from various sources such as the UN development goals, corporate responsibility frameworks and the science of climate risk, vulnerability and adaption. These include modelling tools for life cycle analyses, decarbonisation pathways, and asset optimisation strategies for greenhouse gas reduction.

In his annual note to investors, Larry Fink, CEO of the world’s largest asset manager BlackRock, has become increasingly focused on sustainability and climate change. The investment community took notice of his statement in 2018 that climate risk is investment risk. Fink’s 2021 letter encourages companies to integrate ESG issues into their investment strategies. Companies should “have a well-articulated long-term strategy to address the energy transition, including a net-zero compatible business plan”. BlackRock, ranked 192 on the Fortune 500 for wealth, is setting an ambitious 2030 net zero target for itself, although the realisation of such ambitions is being questioned by informed stakeholders.

Globally, sustainably invested assets under management have increased from $22 trillion in 2016 to $35 trillion in 2020. The difference between traditional sustainability and corporate social responsibility (CSR) is in the area of governance, where the leadership has a duty to ensure the balancing of outcomes for the triple bottom line – policy, purpose, and profits. This is implemented through management systems covering strategy, risk management, performance tracking and disclosure.

More sustainable and transparent measures are implemented progressively through planning as well as incentivising managers, shareholders and the supply chain. The journey and story of ever more sustainable organisations and the potential benefits for consumers and the wider community, are shared as a journey of improvement.

ESG relates to the three non-financial factors that create value and reduce risk, and is synonymous with sustainable and socially responsible investing. Paradoxically, these non-financial factors are starting to have financial implications. Higher performance in ESG benefits shareholder value for listed companies, improves revenues and provides access to lower cost finance. ESG can lower operational risk and create a positive image of the company, making it more attractive to employees, particularly millennials.

Looking at the physical assets developed or renovated as part of an investment or optimisation strategy, the benefits lie in the delivery of tangibly cleaner, greener buildings – lower carbon buildings constructed using less resources, applying more ecological building practices that fit within planetary boundaries, and in the process creating more resilient homes, communities and workplaces.

There are a number of voluntary frameworks in place to enable organisations to benchmark and track performance. Internationally, the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is a framework for consistent reporting of climate-related financial risk, for use by companies, banks, and investors in providing information to stakeholders. The UK government expects all listed companies and large asset owners to report on climate-related risks and opportunities in line with TCFD recommendations, on a comply or explain basis by the end of 2022.

There are a number of tools used to report on the TCFD requirements including GRESB (the Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark), which assesses the ESG performance of property. It is used by the leading Irish development funds and real estate investment funds (REITs). The management component assesses strategy and leadership, as well as processes, risk management and stakeholder engagement. The performance and development components look at asset level ESG data and include topics such as energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and tenant and community engagement.

Key metrics common to most ESG frameworks and tools include:

Environmental: greenhouse gas emissions, energy optimisation, water, waste, materials, biodiversity, physical climate impact and transition risk, building management automation and control.

Social: reputation, human capital, social cohesion, community stakeholder engagement and employee welfare, diversity gender and inclusivity.

Governance: safety, quality management, data privacy and cyber security, culture, reporting and responsible governance.

There are a number of ESG regulatory frameworks, with further versions being introduced each year, both consistent with and replacing the voluntary standards. The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), a global green disclosure body, has been set up to develop a single ESG framework, which aims to provide robust and comparable information for investors, and to tackle corporate greenwashing. Investors are increasingly focused on sustainability and require clearer standardised information from companies on environmental, social and governance risks, which can materially affect the value of their investments.

European disclosure rules under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) sets requirements for disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large companies, such as listed companies and banks, who are required to publish information related to the following:

- environmental matters

- social matters & treatment of employees

- respect for human rights

- anti-corruption and bribery

- diversity on company boards

In tandem with this directive for non-financial disclosure, the EU has introduced a framework for classifying investments. The EU Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation (SFDR) took effect in 2021, requiring that asset managers provide information about their investments' environmental, social, and governance risks as well as impact on society and the planet. Funds have been classified into one of three categories: article six, eight, or nine, based on the sustainability objective. Article eight consists of light green investments and article nine of deep green investments.

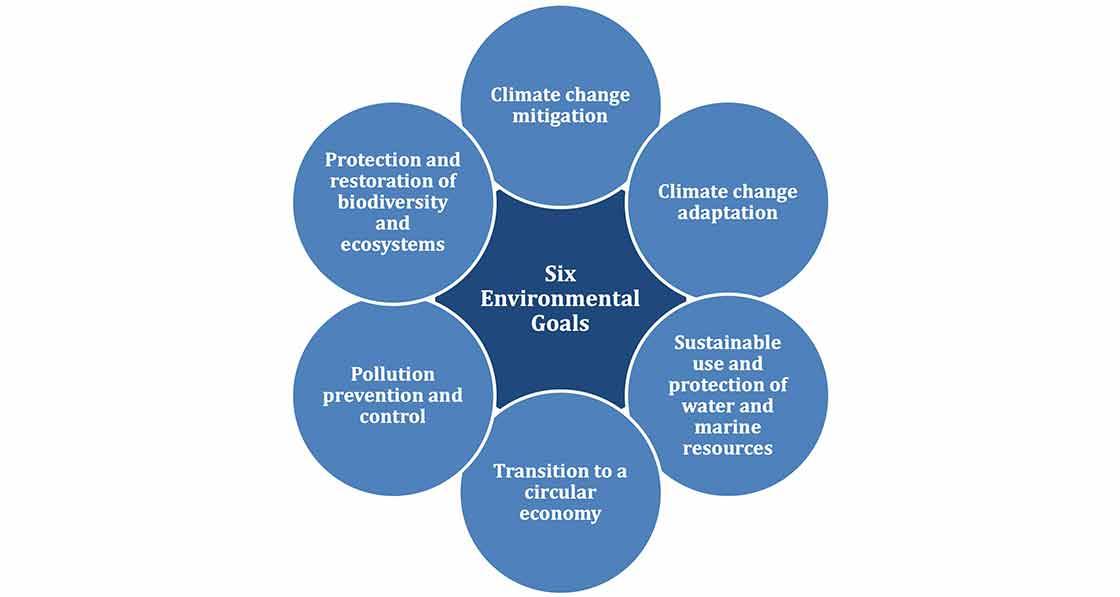

The EU taxonomy delegated act introduces a green classification system, establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities. The taxonomy provides companies, investors and policymakers with appropriate definitions for which economic activities can be considered environmentally sustainable. Its purpose is to provide a more meaningful and detailed definition of the activities that can be defined as green. Activities such as property development, acquisition, leasing and renovation, must be aligned to the definitions in order to be classified as a green investment and to access lower interest green finance.

ESG & buildings

ESG is becoming a key driver in making sustainability mainstream. Development companies are expected to have a social and environmental focus, with pressure applied to have a positive social impact and sustainable footprint in addition to financial performance. Many large organisations will not consider entering into lease agreements for new buildings unless the highest standards of sustainability can be demonstrated through recognised benchmarking tools. If the financial sector is going from laggard to leader, what impact will this have on the standard of future buildings? Is it likely that the rise of ESG as a driver for more sustainable buildings will invariably create a more prominent role for the passive house standard?

ESG rules are becoming more data-focused and robust, with the industry adopting proven approaches to energy performance, health and comfort. ESG analysis relies more on approaches that have solid building physics and science-based targets, that are proven to deliver robust buildings, with investment strategies that are considered futureproofed against both optimistic and pessimistic future climate scenarios. A clear analogy is the impact of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive.

Financial sustainability standards and regulations are likely to have a real impact where they focus the market on enhanced metrics and clearly understood targets. Setting higher standards encourages and incentivises market forces to react and create more progressive and cost-effective measures.

Of particular interest to built environment professionals is the emphasis within ESG disclosure on addressing future impacts on an asset or investment lifecycle, and presenting this as a present-day cost or opportunity. This can include future proofing physical climate risks or a marketplace transitioning rapidly to net zero carbon. This is plotted on a 10-to-30-year timeline, where the impacts associated with changing market sentiment, or ever more stringent regulation of carbon emissions and water use, are traced back to inform sustainability measures in design and management of assets. This could see investment managers setting sustainability targets for the current planned pipeline of new developments, as well as in the renovation and fit-out of acquired assets.

This has the potential to utilise standards that reach far beyond current regulations and push the envelope on voluntary environmental rating schemes such as LEED and Well Platinum, Level(s), HPI Gold and BREEAM Outstanding. But there’s a problem: at enhanced levels of sustainability performance, many asset comparison and rating tools become limited in accuracy for predictive analysis. Increasingly, tools and standards that more accurately predict operational energy and can evaluate site-specific overheating risk are being deployed, such as the passive house standard, and the tool used to design passive houses, PHPP, along with NABERS UK and more sophisticated dynamic simulation tools from IES-VE and TAS.

The question for designers, specifiers, contractors and suppliers is how they can plot their own pathway to 2030, noting that 2030 is only as far away in years as we are from the end of 2013. Will the hatch patterns on architects’ drawings in 2024 look materially different to those in place now, taking regard of the high embodied carbon of current NZEB standard developments and the availability of Environmental Product Declarations?