- Blogs

- Posted

Housing for all: a plan in need of a story

Under its new housing plan, the government wants the state to acquire more land for housebuilding. But why has it failed to use the vast land banks it already owns? Mel Reynolds runs the rule over the figures.

This article was originally published in issue 39 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

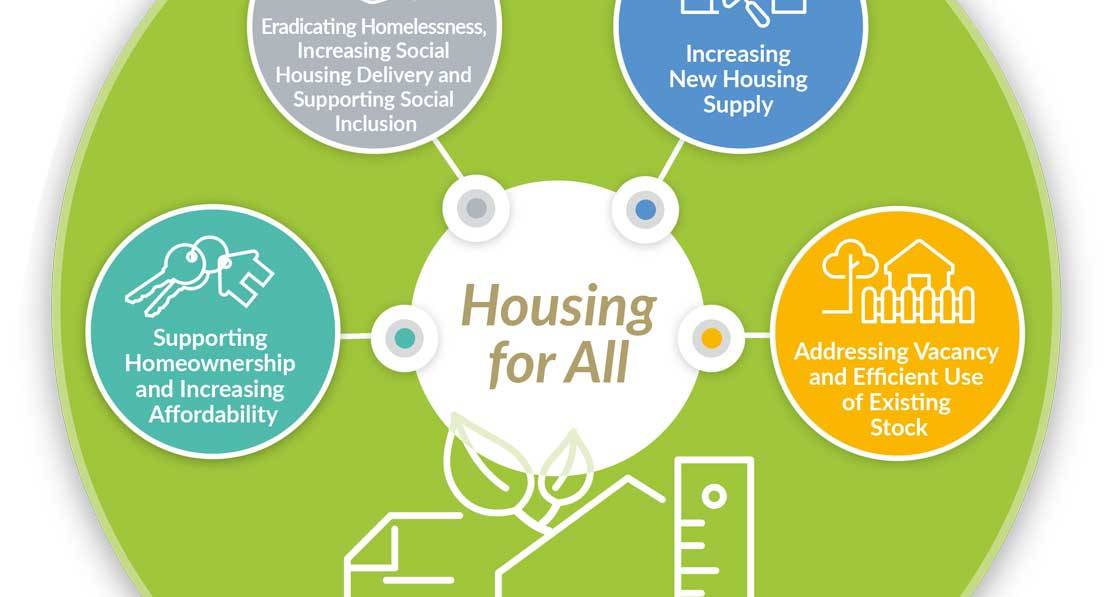

September saw the launch of a new housing plan for Ireland, with ambitious targets for social, private and subsidized private housing. The new plan has a raft of measures, some aimed at increasing land available for state building. Most of the initiatives are aimed at the private sector which, as we know, is subject to the winds of market forces and may not behave in the way predicted. The one component of the plan which is in complete state control is social housing, and in particular local authority building. The annual target for social homes in the new housing plan is 9,500 per year. So, let’s run the rule on the performance of the state’s previous plan, Rebuilding Ireland, and see how effective it has been at building on land it already owns.

State funding & land capacity

Two things are fundamental to building: money and land. The state has an abundance of finance, as demonstrated by the €20 billion committed to the Housing for All plan. In 2018, an audit confirmed that local authorities owned 1,317 hectares of zoned residential land with the capacity for 48,724 dwellings. These figures exclude the considerable land banks owned by other semi-state bodies such as CIE, ESB, Coillte, Dublin Port and the IDA. The audit found that the four Dublin local authorities owned enough zoned residential land for 29,377 dwellings.

So, has the state been so active with house building that it has exhausted older land banks and now needs even more, as this new housing plan suggests?

Local authority turnkey purchases

The Department of Housing has a track record of re-defining inputs to meet targets. In order to inflate ‘build’ figures, the department classifies ‘turnkey’ homes, meaning new homes purchased from the private sector, as ‘builds’. This gives the impression of increased local authority activity. The headline ‘build’ figure quoted by ministers and officials for the four-and-a-half years from the middle of 2016 up until the end of 2020 is 15,962 dwellings in total. Impressive, but somewhat exaggerated as two out of every three, a total of 10,234 new dwellings, were in fact purchased new homes built by developers on private land.

Local authorities bought three out of every ten of these purchased dwellings, and approved housing bodies (AHBs) bought the rest. Stripping out this ‘grade inflation’ will give a more representative view of actual state building activity on state-owned land.

Local authority builds

In this same four-and-a-half-year period local authorities built 4,326 homes (an average of 961 per year), and out of this 1,492 local authority homes were completed in County Dublin (an average of 332 per year), where demand is highest.

AHBs were also active — in the same period they completed 1,402 social builds nationwide (an average of 312 per year), and of these 607 were in County Dublin (an average of 135 per year). These figures suggest that after almost five years of Rebuilding Ireland, only 12 per cent of local authority land capacity had been utilised nationwide.

In County Dublin, local authorities and AHBs utilised just 7 per cent of available land capacity in the same period. It would appear that the state doesn’t need any more land, it needs to use the vast land capacity it already has rather than accumulating larger land banks.

The new Housing for All plan aims to increase the annual average social housing build output more than sevenfold, from 1,273 homes to 9,500 per year. This may be unrealistic as it can take a minimum of 18 months (and sometimes quite a bit longer) for local authorities and AHBs to get through the department’s four stage approval process.

It is likely that the only way the state can meet ambitious targets is to expand the ‘turnkey’ new home purchase programme, an expensive way, particularly in Dublin, to inflate ‘build’ output on paper. Current budgetary constraints on new borrowing until 2023 suggest that leasing of private homes by local authorities may well expand, particularly in Dublin, contrary to the new plan’s stated intentions.

There is an established narrative that private equity firms are muscling-out first-time buyers by purchasing and leasing entire developments in advance of completion. But the same argument can be made towards the government which appears to be doing precisely this, at a much larger scale, while hoarding vast land banks. These figures throw up more questions than answers. The state is doing very little with a lot of land it already owns. Does it need more from other semi-state bodies? Why is the state about to go on a spending spree purchasing land from the private sector?

Moving existing state land assets from one balance sheet to another and continuing reliance on the private sector for delivery may eventually lead to complex public private partnerships — like at O’Devaney Gardens in Dublin 7 — which if not structured properly, may result in significant wealth transfers from the state to the development sector.