- Blogs

- Posted

The prebiotic passive house

As understanding grows of the importance to human health of good bacteria in our environment, and new hospitals in the US start to undergo ‘prebiotic’ treatment, Dr Peter Rickaby asks how long it will be before microbiology becomes a core part of building design.

This article was originally published in issue 24 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

My last column here was retrospective, so it seems appropriate to be more speculative this time, and look to the future of sustainable buildings. Where might we be going and where are the pitfalls?

I have been encouraged by the burgeoning success of the passive house standard in the UK and Ireland, during the last three years. It is undoubtedly the best strategy for designing and constructing energy efficient small buildings, and it is being embraced by more architects who are persuading their clients to use the passive house approach to make sustainable architecture.

It is pointing the way to a robust, scientifically- based method of meeting the EU requirement for near zero energy buildings (nZEBs). However, I am uneasy about the zealotry exhibited by some adherents of passive house, who seem to think that Wolfgang Feist is the one true God and PHPP is his word.

There may be some merit in this view, but I am reminded of Catherine Nixey’s excellent, witty book about the way in which the early Christians treated the Greek, Roman and Egyptian ‘philosophers’ (i.e. thinkers, scholars and teachers) after the conversion of the Emperor Constantine to Christianity. The Christians demanded only blind faith, and the philosophers’ rational questioning was intolerantly and often brutally suppressed, setting the development of science back by a thousand years.

The comparison with passive house zealotry is perhaps a little strong, but we do need to continue to think about how to make energy efficient, sustainable buildings, and not cling to ideas when they become inappropriate. For example, I find the notion of high-rise office buildings built to the passive house standard absurd – just because they are passive doesn’t make them sustainable, and a large office building has a huge carbon footprint in the transport sector. We shouldn’t be building them, passive house or not.

Another issue is adherence to MVHR – great in new houses but not necessarily the best option for an Enerphit retrofit of a Victorian terraced house, a 1930s semi-detached house or a 1960s flat. MVHR is quite primitive, more sophisticated approaches to ventilation are emerging (e.g. demand control) and we should be prepared to embrace them.

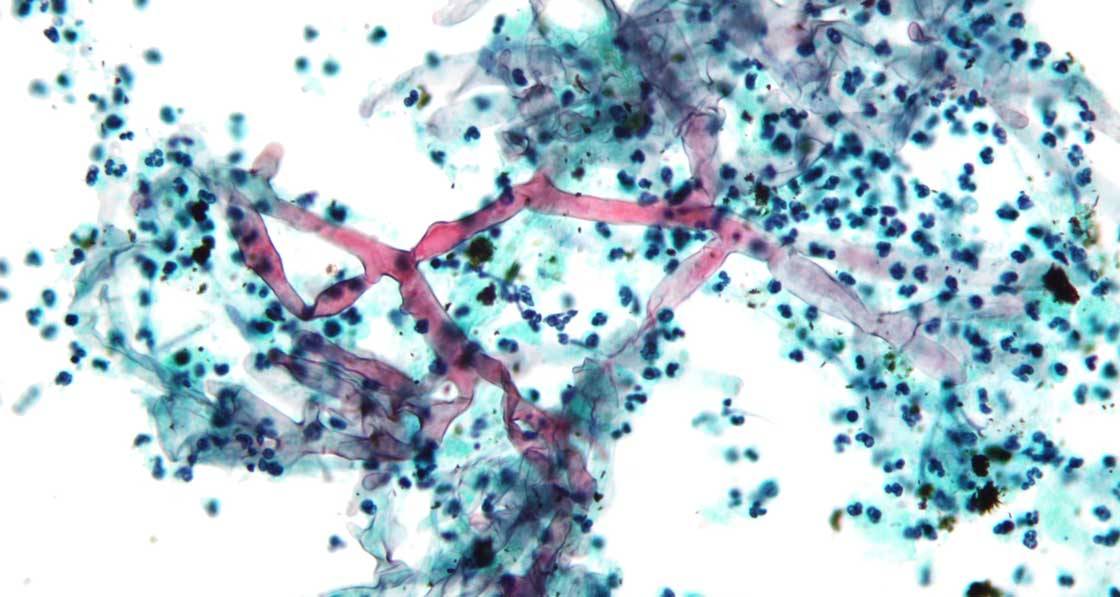

Another book, one that opened my eyes to possibilities for future buildings, is Ed Yong’s account of the ‘biome’ – the invisible community of 3.9 trillion microbes that live on and in all our bodies, and on and in every other living thing, as well as on every surface around us and in all our buildings.

How long before we have microbiologists on our project teams, pre-configuring internal biomes to make them healthy? We each have our own community of microbes, which we share with our colleagues, families and pets, and the microbial communities in our homes are unique to our individual households. Microbes are everywhere – on every wall and floor, every door-handle, every work surface.

Keeping our built environments healthy is not about keeping them sterile – devoid of microbes, which is almost impossible – but about ensuring that the microbial communities are dominated by benign species that contribute positively to our ecology and keep malignant species at bay.

In health care, individuals can be given ‘prebiotic’ doses of good bacteria to bring their biomes back into balance, and so, it turns out, can buildings. Simply opening a window admits good microbes from the soil and air outside that re-balance communities of internal microbes and help to suppress the malign species that can accumulate and make us ill.

So, is sealing our buildings and supplying filtered ‘fresh’ air through ventilation systems necessarily a good thing? It might be appropriate when the external air quality is poor – because of PM10 pollution for example — but elsewhere microbiology offers a new approach to sick building syndrome.

Already, new hospitals in the US have been given prebiotic treatment before occupation, to ensure that the internal microbial ecology will be benign and suppress malign species. Similar treatment of new homes, to suppress pathogens, remove microbes that don’t suit us, and provide precisely- tailored biomes to support our families’ health, cannot be far away.

We argue now about how to ventilate passive houses, but how long will it be before we have microbiologists on our project teams, pre-configuring internal biomes to make them healthy for us?

I think we can be sure that the passive house approach to building design is of its time, and coming of age. But the sustainable buildings of the not too distant future will be so unlike the ones we are building today that we may hardly recognise them.