- Insight

- Posted

Deep retrofit and stimulus

With governments across Europe looking for ways to jump start their economies following the early impact of Covid-19, attention is increasingly turning to deep retrofit. But while there is strong evidence that deep retrofit could play a major role, the devil will be in the detail – and the challenge of dramatically upscaling a nascent industry shouldn’t be underestimated.

This article was originally published in issue 34 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

In April, the Financial Times gave the world’s governments a grave warning. “The Covid-19 pandemic has shown the lethal folly of ignoring expert warnings about the need to be ready for calamity... This should be uppermost in leaders’ minds as they struggle to rebuild stricken economies.”

The leader writers urged governments to use their spending power “to help stimulate a recovery… that does not lock in a fossil-fuelled economy. The situation could not be more urgent; for the world’s beleaguered workforces, and also for the climate.”

The coronavirus pandemic is expected to cost the global economy between $6tn and $9tn; this prediction doubled between April and May. The International Labour Organisation predicted cutbacks equivalent to nearly 200 million full-time workers would take place between April and June of this year. The UK and Ireland, who in common with much of Europe both had severe lockdowns lasting several weeks, are suffering major economic stress.

And climatologists are predicting that 2020 could be the hottest year ever recorded. The last 12 months have seen accelerating ice melt and record temperatures near both poles. Carbon dioxide levels have just topped 416 parts per million, probably the highest level for 800,000 years.

The FT leader joined an international chorus calling for green rebuilding. The United Nations told governments to “build back better” — more sustainable, resilient and inclusive. The International Energy Agency is urging nations to make clean energy technologies, and energy efficiency in particular, a key part of stimulus packages.

In the EU a “green recovery alliance” of most member states, including Ireland, and a slew of large corporations, has signed a joint statement warning that “Covid-19 will not make climate change and nature degradation go away” and that running to panicked economic fixes that lock in fossil fuel use would be counterproductive.

In Ireland, there is a clear focus on construction – retrofit and new build – to restart the economy. Business confederation Ibec is campaigning for its Covid recovery plan ‘Reboot and Re-imagine’, which calls for government support for new construction, in particular social housing, and for “an ambitious national deep retrofit programme” with a new delivery and financing model to upgrade buildings to B1 and A energy ratings.

And as Passive House Plus went to print, a draft programme for government had just been agreed between Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and the Green Party that contained a commitment to retrofit 500,000 homes to at least B2 rating over five years.

Just transition

In the UK, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) wrote in May to the four UK governments urging them to rebuild after Covid-19 “whilst delivering a stronger, cleaner and more resilient economy”.

Covid has hit disadvantaged communities harder, in multiple ways, and the CCC was forthright, calling on UK governments to embed fairness as a core principle of a green recovery.

“The benefits of acting on climate change must be shared widely, and the costs must not burden those who are least able to pay, or whose livelihoods are at risk,” the CCC’s letter said.

CCC chief executive Chris Stark, and Julie Hirigoyen, chief executive at the UK Green Building Council, both point out that construction and retrofit is one of the best ways to create jobs, per £1 or €1 invested. “Energy efficiency is ‘shovel ready’ – with labour-intensive projects rooted in local supply chains,” Hirigoyen says.

A report for the International Energy Agency (IEA) agrees, stating: “When homes are upgraded to higher efficiency standards, more than half of the total investment typically goes directly to labour.”

A very comprehensive analysis of the value of green versus ‘standard’ stimulus packages by the Smith School of Enterprise and Environment, at the University of Oxford, confirmed that boosting green construction is a highly effective way to create jobs, and thus repay the investment long-term.

A team of 230 economists from around the world was asked to rate 700 stimulus packages implemented after the 2008 financial crash. They found construction projects retained more of the investment locally, adding that clean energy in particular (both renewable generation and energy efficiency work) was “helpfully very labour intensive in the early stages” with up to three times as many jobs being created per £1 invested, compared to investments in fossil fuel.

Unconditional airline bailouts, by contrast, “performed the most poorly in terms of economic impact, speed and climate metrics.”

Wider benefits

As well as creating jobs, construction-focused green stimulus brings numerous other benefits, in particular to the least well-off. This was highlighted in a report last year by the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, calling for a just transition for Irish households and workers affected by the planned closure of carbon-intensive peat-burning power stations in the Irish midlands.

The group quotes the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland, which estimates that tackling the one million older Irish homes that need deep retrofit could add €35 billion to the Irish economy: “This represents a significant opportunity to improve health and well-being for the occupants, particularly the significant numbers suffering from energy poverty… as much as 28 per cent of households in 2015.”

New housing, particularly the construction of well-designed, low energy social housing, also brings large social returns. When social housing is constructed, new tenants enjoy lower rents, better living conditions, and more security than the average tenant in the private rental sector – and far better than in temporary accommodation.

Tenants and the community at large benefit, including economically, as research by HACT (the Housing Associations’ Charitable Trust) illustrates. People moving into social housing are likely to enjoy improved mental and physical health, to be better able to find and retain a job, they are less likely to be a victim of crime, and their children will be able to stay in the same school, benefiting their education, this research shows.

Above clockwise from top left: Irish Green Party MEP Ciaran Cuffe; Julie Hirigoyen of the UK Green Building Council; UK Committee on Climate Change chief executive Chris Stark.

How to finance a green rebuilding

Funding energy saving work through utility bills, as has been done in the past ten years or so in the UK, is popular with governments because it is “off balance sheet” (i.e. kept out of the state’s own budget).

But funding via energy bills is regressive. It hits the poorest hardest and has become politically unpopular as a result. An expanded, ambitious programme of the kind that is needed to meet carbon targets cannot realistically be imposed on bill payers, many of whom will see little or no financial return. Yet governments seem to have had a bit of a blind spot with regard to green construction.

Regarding retrofit in particular, the case has repeatedly been made that deep retrofit should be seen as a national investment — it is effectively an infrastructure programme. And it works economically in those terms. Medium-to-long term, investment in green construction pays back amply to the state, many researchers have concluded.

Verco and Cambridge Econometrics examined this for UK climate change think tank E3G in 2014, and calculated that a 15-year programme of deep energy retrofit would return £1.25 to the government per £1 invested, from the increased tax take resulting from job creation as well as from supply chain activity, increased household disposable income, and a lower state welfare bill.

This positive rate of return makes government borrowing justifiable as an approach for funding energy efficient construction – in the same way that any national infrastructure investment is justified.

For big infrastructure projects, governments generally like to leverage private sector finance, to increase the total size of the programme. Given that energy efficiency work improves the value of a property, property owners can be expected to contribute something, either at the time of the work, or at the moment of property sale.

However, incentives are generally still required to overcome initial resistance, compensate for the costs of disruption, and also to ensure uniform, high standards of work. In Ireland, Paul Kenny of Tipperary Energy Agency, who runs the SuperHomes deep retrofit scheme, believes grants of 35% or so are necessary to catalyse homeowner investment.

Tax incentives (for example stamp duty relief) are one way of managing this, as are direct cash contributions to the work. Another incentive, which could be complementary, is to offer subsidised lending. This can be organised as a rolling loan fund, which has worked well in pilot schemes in the UK in the past. Low cost finance is offered along with support to ensure the work carried out is properly designed and project managed. MEP Ciaran Cuffe suggests that in Ireland, the European Investment Bank could support something similar, and back a state guarantee for loan finance for deep retrofit.

There is also the option of independent finance through the private sector. Energy retrofit is a market that is reportedly of growing interest to private investors who are seeking ‘green’ and future-proofed investments. Analysts are warning investors that oil stocks are no longer safe, as fossil fuels are increasingly identified as problematic – a trend that if anything is accelerating in the Covid crisis.

Lending into future-proofed, low-carbon property is starting to appear attractive, though investors will however be anxious to see quality assurance of the work they are backing (this was one of the drivers for developing the UK retrofit quality protocol, PAS 2035).

‘Ethical’ investors are also being courted by the social housing sector. According to the Financial Times, a group of large housing associations, investors and financial experts is actively looking for ways it can raise money by quantifying what they do in terms of environmental and social performance, to attract so called ESG (environmental, social and governance) investment.

One of the criticisms levelled at infrastructure investments like airports or high speed rail is that they do not always distribute benefits to the most in need. Construction work, as we have seen, is jobs-intensive, and wherever there are people, there are houses to retrofit and new houses to build. However, there are still concerns that to maximise community-wide benefits of any regeneration and retrofit programme, there also needs to be local control.

The UK Green Building Council has proposed a couple of structures that could enable a national retrofit programme to be fine-tuned to suit each area, such as local authority funds and community social enterprises.

Do as much as you can well

The calls to ‘green stimulus’ action emphasise the urgency of the Covid and climate crises, and the need for ramping up of action to match. The International Energy Agency, for example, at first glance seems to be promoting a gung-ho approach to green energy and retrofit: “Early action can create jobs quickly by focusing on what is already in place and ready to be scaled up.” But they go on to warn: “Supply chains and capacity will be crucial. If new programmes quickly increase demand, can the market respond? Are good products available? Are installers ready to meet demand at sufficient levels of quality and safety?”

Jonathan Atkinson, manager of the Manchester People-Powered Retrofit programme, fears they are not – and says that changes at many levels are needed. In a blog for the Centre for Alternative Technology he warned that the existing model for procuring energy efficiency work in the UK has led to a ‘race to the bottom’ in terms of costs and quality. “Poorly planned energy supplier-funded works delivered to unrealistic timescales by badly trained staff led to widespread damage, leaks, poor quality home environments and aggrieved residents.”

As the IEA put it: “Governments in a hurry to generate activity can be tempted to lessen the focus on technical standards or required efficiency levels, but this can be a false economy in the longer term.” This is not a mistake we can afford to make.

The UK’s new PAS 2035 retrofit standard represents a major step forward in assuring quality in retrofit. Requirements include design by appropriately qualified professionals, and an insistence on effective ventilation whenever there is a risk of inadequate air exchange. At national level though, it has not yet been formally adopted.

In order to overcome the dangers of inadequate and even harmful installations, there is wide agreement that more and more appropriate training is urgently needed. Even in the small pilot whole-house retrofit schemes currently being funded by the UK government, demand from homeowners risks outstripping the supply of suitably qualified advisors and installers.

Manchester’s People-Powered Retrofit programme is one of these pilots, and Jonathan Atkinson is concerned. “There is a skills shortage that has to be addressed to enable safe and effective retrofit to be delivered. There is no point in ramping up funding for retrofit unless it can be delivered properly,” he writes.

“Luckily there are great, practical training models out there that can be replicated. Investing in the people doing the work absolutely must go hand in hand with investing in the work itself, or we will be storing up all kinds of trouble.” In new build too, construction to genuinely low-energy standards requires particular skills and knowledge: one of the reasons passive house projects often show higher costs is because clients are effectively investing in skills training on behalf of the whole construction sector — the necessary skills and knowledge aren’t part of mainstream construction education and apprenticeships.

Experience has shown that many construction workers adapt readily once the time and resources have been found for training, so there is a clear opportunity during a construction slow-down to support workers to remain in the industry and to gain the skills needed to “build back better”.

One group who could be targeted are those same young people whose skills training and job prospects are most impacted by an economic crisis. The damage is already occurring: reportedly just 20% of UK apprenticeships due to start in April came to fruition.

Research by the Resolution Foundation shows that remaining in education or training offers long term benefits to job market entrants, compared with trying to go straight into work in a depressed job market. The foundation has called for extra support to be put in place urgently, so young people can gain an extra six months of training – something many currently struggle to afford.

The Green Party in Ireland has similarly called for the introduction of fast track apprenticeship programmes, to train the 20,000 workers its estimates are required to adequately retrofit the national housing stock. The programme for government that the party agreed with Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, just as Passive House Plus went to print, contains a commitment to overhaul apprenticeships and training to ensure there is a skilled workforce for delivering mass retrofit.

Politically popular?

According to recent news reports, polling shows a clear majority of the population in each of the 14 major economies, from China and India, to Russia, the US and Brazil, thinks climate change is as serious as coronavirus. And in the UK, 70 per cent are in favour of accelerating climate action by moving the government’s zero-carbon target from 2050 to 2030.

People are also questioning economic norms: polling has found a majority of the UK public, for example, wants ministers to focus on improving health and wellbeing over economic growth, even after the immediate threat from the coronavirus has passed.

Nick Robins from the London School of Economics (LSE), one of the authors of the Smith School study, pointed out that after the global financial crisis of 2008 a massive proportion of ‘recovery’ investment was in his view misdirected into fossil fuel projects. In an interview, he told the BBC: “If we have any hope of combating climate change, we must make absolutely sure we do it better this time.”

So often the argument is heard that we can’t afford to invest in more sustainable approaches to building and upgrading our homes, schools, shops and offices. It is becoming increasingly clear that we can’t afford not to – and that the world’s ordinary people understand this perfectly well. Failing ourselves, and young people in particular, on either a Covid rescue, or on climate rescue, would be unforgivable.

Will economic growth save us?

Green stimulus’ or ‘green recovery’ generally has its goals framed in terms of boosting or restoring economic growth. Yet at the back of our minds, many of us are aware that the headlong striving for growth at all costs may be what has got us into the climate crisis in the first place.

An exception to the ‘growth growth growth’ agenda is the city of Amsterdam. In the Covid recovery plan the city produced in April, its main goals, unusually, weren’t about growing the economy or increasing gross domestic product. Rather, they were about making the city better for people and the planet, in an analysis based on the principles of ‘doughnut economics’, a concept developed by the Oxford economist Kate Raworth.

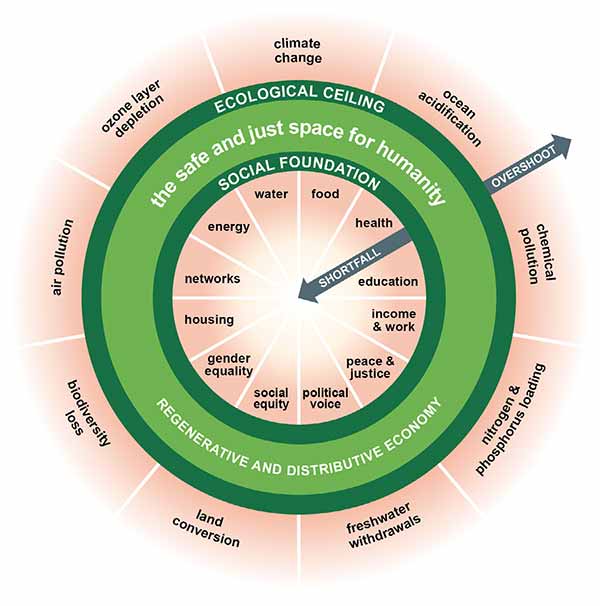

The doughnut envisages society flourishing in a sphere between a basement of minimum, decent living standards for all and a ceiling of ecological limits (see diagram above).

Instead of using the gross domestic product as the measure of society’s success, doughnut economics enables policymakers to visualise numerous dimensions of wellbeing – economic, health, social, environmental – on an equal basis. They can identify where there is a shortfall in basic needs for citizens, and where there is excess that is taking too much from the rest of the world, or threatening its future.

“It gives us the opportunity to put those other values — like social interaction, health and solidarity — much more in the forefront of how we’re going to recover from this shared crisis,” Amsterdam’s deputy mayor Marieke van Doorninck explained.