- International

- Posted

International selection - Five ground-breaking buildings

What do certified passive houses in Germany & France, community centres in Austria and the USA and the 2011 Solar Decathlon winner have in common? Passive House Association of Ireland chair Martin Murray of Martin Murray Architects finds inspiration in each of the five ground breaking buildings

The emergence of Passive House Plus like a chrysalis from the old shell of Construct Ireland is a further step along the way in the extraordinary contribution Ireland has made to the development of this international low energy standard over the past ten years.

Low energy design has been a slow burner across the construction industry both here and abroad over the past ten years. There’s no doubt that Construct Ireland played a key role in maintaining it at the centre of debate and pushing for continuous improvement of energy performance – not just in the buildings themselves, but also by the practitioners, on both sides of the drawing board.

Buildings designed to the standard of passivhaus – or passive house – are exemplary low energy sustainable buildings with greatly reduced CO2 emissions and very high comfort and environmental standards. They require a sophisticated combination of good orientation, a highly insulated fabric, low air permeability, minimal thermal bridging, excellent triple- glazed window components and efficient heat recovery ventilation. The combination of these disparate elements through the PHPP (Passive House Planning Package) software gives rise to robust, efficient low energy designs. And Ireland has an ideal climate for their realisation.

A recent potted history of the evolution of these sustainable buildings forms the basis for my selection. The buildings extend back to the beginning of the passive house standard through to sophisticated iterations at both a commercial and domestic scale, and unto two final projects which begin to capture a wider environmental agenda.

They seem to me to reflect not the overt visually attractive structures favoured by architectural magazines worldwide. Rather they are of a different compelling beauty, a different ilk. To quote the visionary engineer Buckminster Fuller (1895 -1983): “When I’m working on a problem, I never think about beauty. I think only how to solve the problem. But when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong.”

So with these sentiments in mind, please read on and enjoy some very beautiful sustainable buildings.

Passive house, Darmstadt

It is perhaps always presumptuous to suggest that something is ever truly the first of anything. There are cultural and technical paradigm shifts that build up to a point in time when what is produced becomes noted as the ‘first’ embodiment of an ideal.

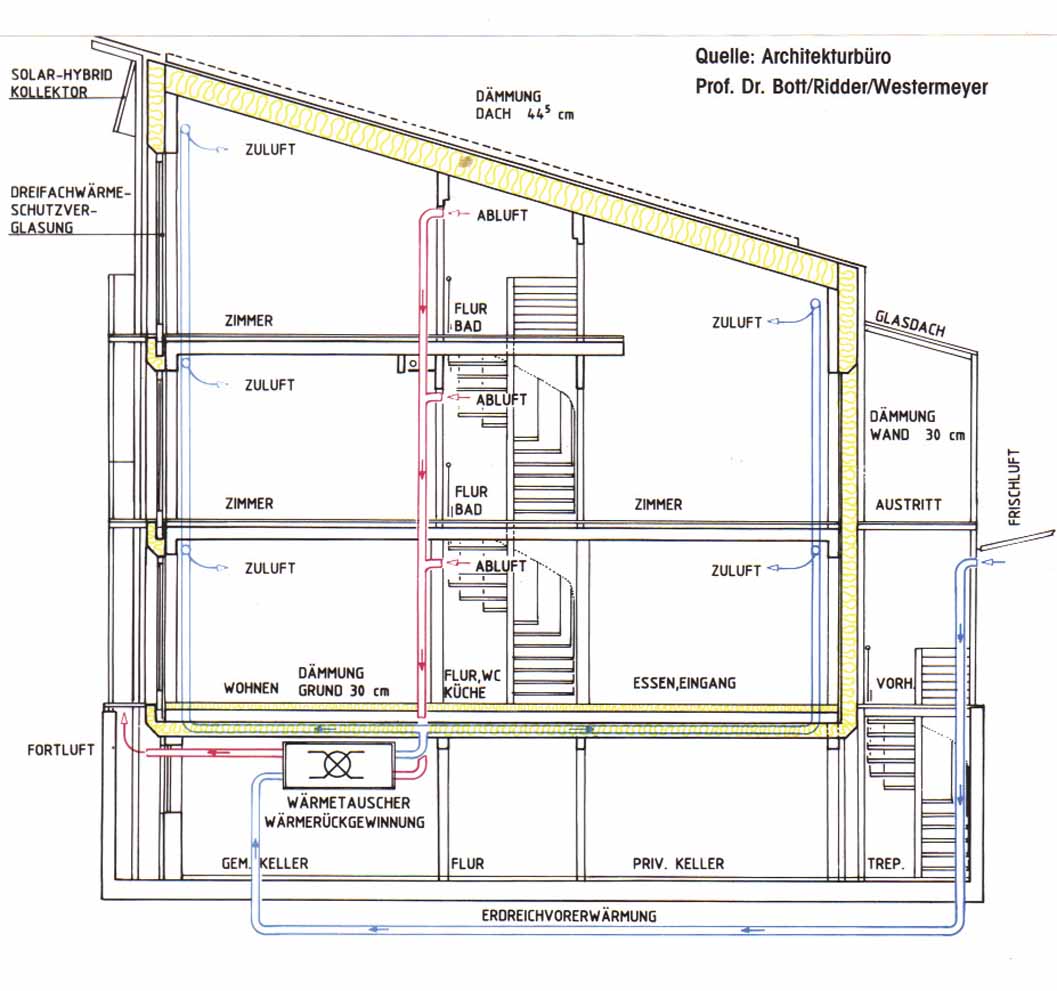

So it is with one of the first passive houses built in 1990/91 to design plans created by Profs Bott, Ridder and Westermeyer for four private clients – one of whom happened to be the physicist Prof Wolfgang Feist, who went on to become a founder of the Passive House Institute. The construction of this multi-unit development is based on research work which evolved throughout the 1980s in Europe – particularly Sweden and Denmark – Canada and America as the realisation of the need for low energy buildings became paramount. Three of the main protagonists in this regard were architectural professors Bo Adamson and Robert Hastings along with the aforementioned Wolfgang Feist.

The completed building is three storeys over basement with living spaces orientated toward the south, with a north facing facade containing a single-glazed entry area allowing covered access to the basement storey.

Some iconic buildings bear testimony to cultural, social or technical shifts in ways that are visually striking; the works of, say, Le Corbusier, Mies, Erskine, and Piano & Rodgers are exemplary in this respect. This passive house is more reticent, it contains all of the characteristics which have evolved since 1991, toward becoming the principles of passive house design, and it is, in this respect, iconic and beautiful

The low energy characteristics include compact design and good orientation giving measured solar benefits, an enclosing fabric with a high level of thermal performance, minimal thermal bridging, triple-glazed windows and heat recovery ventilation. All combined, the net result is a very low heating usage of 9.2 kilowatt hours per square metre per year. The project has underpinned a significant amount of active monitoring across 20 years since its construction. It has been exemplary in proving passive house principles, and has led to the development of products and mechanical systems appropriate for passive house construction. The level of airtightness achieved was amazing: 0.22 air changes per hour at 50 pascals of pressure. Further testing ten years later showed no reduction in this value.

It’s important to emphasise that the house was designed to be both a comfortable home and a test-bed laboratory of sorts, and so at the beginning the cost benefits relating to all the key component design decisions were analysed. This gave rise to the understanding that all household energy use within the home had to be understood to avoid fall back toward inefficient means of substitute heating even within the highly insulated fabric. In total, eight different research projects fed into the knowledge which made the building possible. At the time in 1991, the research costs and special construction costs amounted to an increase of almost 50% over baseline building costs. These were grant assisted. Today in Ireland the additional cost of building to passive house design is as low as 5 to 8% depending on the detail of the project.

This iconic building was finished in October 1991 and has been continuously in use and continuously monitored ever since. It gave rise to the development from 1996 of preliminary versions of the PHPP software. Since then the comforts of the passive house – warmth throughout with exceptionally good air quality – have been available to all who choose to pursue them, and at a reasonable price. PHPP has subsequently founded a basic scientific approach to the design of many types of passive house buildings – one such being the community centre in Vorarlberg.

Ludesch Community Centre, Vorarlberg

A well designed and briefed community centre has great potential to draw together a neighbourhood, creating an evocative and iconic image within the minds of its users. Built by the 3,300 citizens of Ludesch, the passive house community centre within the province of Vorarlberg is just such a building.

The germ of the building initially evolved through a broader low energy programme launched in 1998, the e5-Programme for Energy Efficient Communities. Its intention was to support municipalities in their efforts to raise energy efficiency, and increase the utilisation of renewable energy sources. Thirty-four communities and one region joined the e5 programme, and for the municipal area of Ludesch the design and construction of the community centre was the natural development of the overall initiative.

As with most successful projects the initial briefing was carefully considered, with over six years of planning going into the making of the building, which was eventually completed in 2005:

The building had to achieve low utility costs and an optimal ratio between total costs and the lifespan of the building constructed to the passive house standard and built in adherence to ecological guidelines. It was important that biomass energy be used for heating and lumber from the silver fir tree in the surrounding forests for construction of the building, walls and furniture.

Designed by Architekten Hermann Kaufmann, the building is 3,135 sq m in area, or 14,500 cubic metres in volume. The ground floor contains a multi-purpose hall, town library, mail room, coffee shop, rooms for a children‘s play group and two businesses. Upstairs there are municipal offices, an information centre for midwives and some additional offices for private service providers.

The key architectural feature of the building is the shaped entrance courtyard which is roofed with inclined glazed elements containing 350 sq m of solar photovoltaic (PV) cells. The creation of this village square as the communicative middle point of the village was one of the key recommendations of the original study groups. The PV array generates 16,000 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity per annum – enough to allow for selling of the surplus into the national grid. Thanks to the e5 programme the overall municipality of Ludesch has a high percentage of PV systems for energy supply – the village has one square metre of PV surface area per inhabitant.

While the entire internal area of the new community centre is equivalent to 22 one-family homes, the building’s energy requirements don’t even exceed the energy needs of two homes. The building, which was awarded the Energy Globe Vorarlberg, is optimally insulated and fitted with heat recovery systems.

The architects relied on local and renewable raw materials such as wood, and excluded any building materials containing CFCs or PVC. Sheep’s wool, for example, was even used to insulate the windows. For this reason also, PVC was also avoided in the ductwork, electric cable casings and floor coverings. The use of solvent containing materials like lacquer, paint or glues was also frowned upon, as well as the use of softeners and substances containing formaldehyde. Cellulose and sheep‘s wool was used extensively for the insulation in the walls, whereby it was accepted that sheep‘s wool was capable of absorbing poisonous vapours to a certain degree. The final additional costs of this consistent ecological construction method were only 1.8 %.

The deciding factor for the appearance of the centre was the use of timber. The consequential use of the rough hewn, untreated wood of the silver fir on the building‘s facade is responsible for the appearance of the three structures. The direction of the planks creates diverse block diagrams and calls forth magical light and shadow effects on the building. The silver grey patina that is formed by weathering will lend the building an additional vibrancy in years to come. The one metre wide overhangs aid the constructive protection of the wood. Inside, the untreated silver fir wood creates a warm atmosphere, and gives the spaces a friendly open character. Because of this, the community centre has a vibrancy and presence which is unusual for an administrative building. It sets high standards for the entire process of implementing community building projects everywhere.

Private house, Île-de-France

More so than the commercial and community passive house projects, the design theme of the free standing private home has been an iconic image in the evolution of the passive house design idiom. Designed by Karawitz Architecture, this single family home on its own plot in the Bessancourt suburb of Paris is a particularly elegant example of this progression.

The house overall has the ideal passive house plan formation with circulation – or servant spaces – across the north facing rear of the block while all living areas – or served spaces – at ground level, and bedrooms at first floor level, achieve a southern aspect.

Consisting of cross laminated columns 600mm deep at 900mm centre to centre, the timber framing module creates a defining but open spatial structure. In this spirit, passive house is perhaps the true technical heir to the original modernism endeavour of open plan flowing design – notwithstanding the truer realities and challenges of noisy and messy children, and spatial privacies!

The shape of the house follows the generic domestic shape of old farmhouses in this area of northeast Paris. Its modernity is expressed in a stripped down simplicity of form which is overlain with a folding bamboo screen to give summer shading and visual privacy during the day. Hopefully the residents discovered the lack of privacy which such gives at night before it was too late! This screen is perhaps without technical merit on the north elevation, covering as it does solid wall, however it evokes again the traditional farm barns in this part of France and will allow a rich patina of age to develop over the years as it goes grey. The architects accept that the bamboo will require replacement over the years.

The only concrete element in the construction is the concrete slab, while the roof mounted u solar PV array gives 2,695 kWh of electricity per annum. Overall the 161 sq m house uses only 4,300 kWh of energy per annum, reflecting the Factor 10 principle which pervades most passive houses – the house uses 90% less energy for heating than a typical house in the area.

The rest of the timber framed structure was prefabricated off site with U-values of 0.14 for the outer walls, 0.12 for the roof and 0.17 for the 200mm insulated concrete slab. As one of the first certified passive houses in the Paris area it undoubtedly reflects accurately the elegance and demeanour of the region as a whole.

Painters Hall Community Centre, Oregon

The creation of beautiful, sustainable, low energy buildings is the hallmark of the Living Building Challenge (LBC), an environmental design paradigm which has evolved through the Cascadia Region Green Building Council and the International Living Future Institute, both based in Oregon, USA.

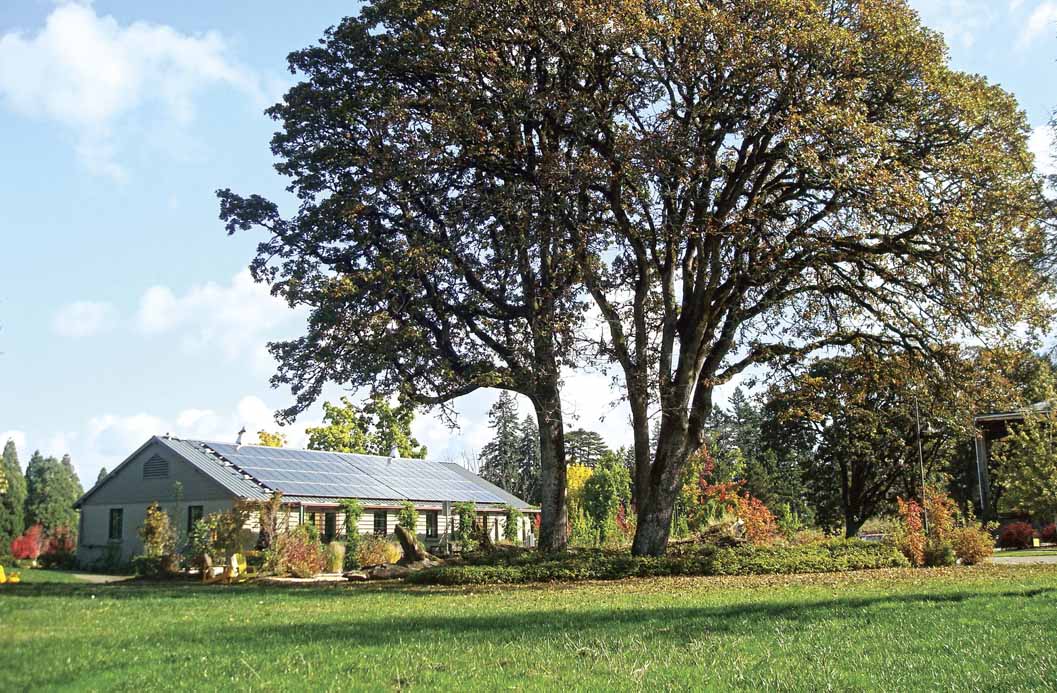

One of the first buildings certified under this rigorous design methodology is Painters Hall, a community centre originally built in the 1930s. Located on a 32 acre mixed use site in Salem, Oregon, the upgraded building has achieved zero energy status, the LEED platinum standard and LBC ‘Petal’ recognition.

The reference to petal recognition evolves from the structural format of the LBC energy primer, which utilises a flower as a metaphor for truly sustainable buildings – self-contained and reflective of the carrying capacity of their site. The LBC allocates markings across a range of ‘petals’ including site usage, water, energy, health, materials, equity and beauty – overall a challenging heptagon of sorts. In the case of Painters Hall, energy, equity and beauty were the targeted recognitions.

The building’s original name evolved from the previous use of the site as a training centre. The intention is to retain its educational links by becoming a meeting and low energy educational centre to reflect the aspirations of the Pringle Creek community as a whole.

The centre uses approximately 20,000kWh of energy per year, but produces 26,000kWh from its roof mounted PV array. A communal geothermal heat pump serves the primary heating needs of the facility. For water conservation low flush and dual flush fittings combined with grey water harvesting contribute to an annual saving in water usage of 12,000 gallons.

Practitioners and contractors should note that during the renovations almost 90% of material waste was diverted from landfill, while a quarter of the materials (by cost) used in the building resulted from active recycling. Additionally all paints, adhesives, and composite wood products used on the project were designated as being low VOC (volatile organic compounds).

A number of environmental imperatives arise from the LBC petals which HAD TO be considered in the design process of the project. The energy petal gave rise to the net zero energy imperative which was focused on the mantra that a kilowatt hour saved on site was less expensive than one produced on site. To this end the walls, floor and roof were upgraded to a high thermal performance using blown cellulose, finished in light internal colours to reduce electrical lighting loads. These strategies were combined with careful selection of light fittings, occupancy detectors, and dimming overrides. At a cost of $300 worth of hardware, a building energy management system, TED, measures total building energy consumption, photovoltaic energy production and individual circuit loads. This device and its software can communicate with web-based programs so that owners can access an energy dashboard via the internet at any time, sharing data with others and receiving weekly summaries by e-mail that compare usage trends.

As is the hallmark of all the buildings in this selection, the attention to detail is paramount. It renders the question poised by the Living Building Challenge: What if every single act of design and construction made the world a better place? It’s a rhetorical question, because in the case of this building they do.

2011 Solar Decathlon Winner, University of Maryland

It is within the university of life that many of us hone our skills, buffeted and knocked by the challenges of the everyday. A different educational experience is to be had through hardcore university research in the form of the projects presented in the bi-annual Solar Decathlon. A low energy building competition for competing universities and technical institutes, the decathlon undoubtedly acts as a portal into what sustainable design will be like in future practice.

WaterShed – the University of Maryland’s winning entry into the Solar Decathlon 2011 – is a solar-powered home that comprises systems which interact with each other and the environment to satisfy the competition brief. Just as Painters Hall placed the consideration of water reuse centre stage, water was a central theme of this project.

The house was to be designed, built and operated to be cost-effective, energy efficient, and attractive. WaterShed carried this energy emphasis through to the next great environmental challenge, water, whereby the project attempts to harvest, recycle and reuse every drop of water which lands on its site.

The panel of judges assess the competing entries across ten criteria: their architectural qualities, market appeal, engineering, educational/communication effort, affordability, “comfort zone,” hot water systems, appliances, home entertainment and energy balance. The resulting complexity creates valuable interaction between students, faculty and professional mentors.

The interdisciplinary team on WaterShed evolved a design which includes a host of innovations. A split-butterfly roof captures and uses both sunlight and rainwater. Constructed wetlands filter storm-water and grey-water. A green roof attenuates rainwater and promotes efficient cooling. A photovoltaic array harvests enough solar energy to power WaterShed all year round. A solar thermal array fulfills all domestic hot water needs. A garden of ‘edible landscapes’ supports community-based agriculture. A patent-pending indoor, liquid desiccant waterfall provides high-efficiency humidity control. And the building itself is an efficient, cost-effective, structural system.

As a competition for third level students, the decathlon is evocative and demanding. In 2007 Spain agreed to organize the first European decathlon and in 2013 the first such event will be held in China. Without doubt the research and effort which goes into each and every design is a loud echo of the work and analysis that gave rise 20 years ago to the Darmstadt passive house.

It’s worth noting that this respect for research, monitoring and analysis, is at last gaining traction within the built environment courses throughout Ireland. Have no doubt that the chrysalis like emergence of Passive House Plus will facilitate further these endeavours. As the proverb goes, “Just when the caterpillar thought the world was over, it became a butterfly."