- Upgrade

- Posted

Bungalow Bills

What does it feel like to suffer the cold, mould and discomfort of a 1960s bungalow, and experience its rebirth as a passive house? The owner of one award-winning project spills the beans.

Additional reporting by Jeff Colley

Click here for project specs and suppliers

Building type: Retrofit and extension to 188 m2 bungalow

Method: Bone-deep retrofit - floors dug out, chimney removed, roof replaced. Warm roof, external insulation, heat pump, MVHR

Location: Monaghan

Standard: Passive house classic

Heating cost: €80/month* * All energy costs – including heating, hot water, lighting and plug loads.

It’s now fifty-two years since Jack Fitzsimmons’ highly influential book of house plans ‘Bungalow Bliss’ was first unleashed on the Irish market. Reprinted ten times, it sold in excess of 250,000 copies, and bears much of the responsibility for the fact that 15 per cent of all homes in the country are bungalows. The Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland estimates that there are 300,000 dotted throughout the Irish countryside, 80 per cent of which have BERs of low D or worse.

Addressing their energy and comfort shortcomings has of course become one of the many building stock challenges we face.

Barry McCarron has answered these challenges brilliantly in the deep retrofit of his family home in Ballinode, Co. Monaghan. He monitored the energy performance of the bungalow for two years prior to beginning the project. The costs came in at €3,711 in 2020/2021 and €4,773 in 2021/2022 – an average of €4,242 per year, excluding standing charges. One passive retrofit later and predicted annual running costs have dropped to €1,082, again excluding standing charges, nearly four times cheaper. The total savings over the life of the mortgage as a result of the project come to €91,627, while the payback period for the additional cost of achieving the full passive house standard is just four years.

‘There’s absolutely no regret,” says McCarron, ‘I believe we’ve made a great investment in our family for the years ahead.’

Though this was his first passive project, Barry McCarron isn’t exactly a stranger to sustainable building. He is the current chair of the Passive House Association of Ireland, is head of business development with South West College, and for the past eight years has been teaching on their passive house designer course. Earlier in his career, he also put in what he describes as three ‘very very educational years’ doing BERs.

His first passive project was always going to be worth checking out.

McCarron says that he and his wife Aisling had always expected that they would build a house on the family farm in Ballinode. Then, in the lean years following the property crash, a bungalow opposite the farm came up for sale. They got it for just €95,000.

‘We lived in it for eight years,’ he explains, ‘but we didn’t really commit to the house. We only did superficial refurb work. We thought we would probably sell it and build new, but the longer we stayed without building, the more a new build came off the agenda and retrofitting came on.’

Wouldn’t it have been easier to just demolish and start fresh?

Maybe it would, says McCarron. ‘But I would have had to apply for full planning permission, which I probably would have got, but with the retrofit, I only had to apply for an extension, and it also avoided the necessity for an assigned certifier and all that comes with new build.’

The big attraction of retrofit however was that it was an opportunity to do something interesting and relevant. ‘I work in a college, and that keeps me away from real life, I’m always on the fringe of projects. This was an opportunity to be involved in a real project and for me, retrofits are a huge part of the picture going forward. I wanted a retrofit project, I wanted to learn as much as I could about it.’

The existing house

This article was originally published in issue 46 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

The McCarron family home, built in 1969, was a typical bungalow. Long, low and compartmentalized, it was rated D2, and had a space heating demand of 324 kWh/m2/yr. In addition to monitoring energy costs in the two years running up to the project, McCarron also monitored temperature and indoor air quality. The average temperature in the kitchen was 17.8 C, relative humidity was 61 per cent, while CO2 PPM averaged 1,050.

The living room wasn’t much better.

‘My bald head is fantastic for picking up drafts. I’m a Liverpool fan, I watch the Champions League at this time of the year. And in our old living room, with the stove on, the temperatures could be as high as 35 C, but the draft from behind the curtains would turn you into a snowman. So my face would be melted but the back of my head would be frozen.’

-

The existing house built in 1969

The existing house built in 1969

The existing house built in 1969

The existing house built in 1969

-

Mould visible in rooms

Mould visible in rooms

Mould visible in rooms

Mould visible in rooms

-

Mould visible in rooms

Mould visible in rooms

Mould visible in rooms

Mould visible in rooms

-

The red line indicates a gap in insulation at top of wall

The red line indicates a gap in insulation at top of wall

The red line indicates a gap in insulation at top of wall

The red line indicates a gap in insulation at top of wall

-

Cavity insulation with massive gap at top including block at wall plate

Cavity insulation with massive gap at top including block at wall plate

Cavity insulation with massive gap at top including block at wall plate

Cavity insulation with massive gap at top including block at wall plate

-

Cavity insulation with massive gap at top including block at wall plate

Cavity insulation with massive gap at top including block at wall plate

Cavity insulation with massive gap at top including block at wall plate

Cavity insulation with massive gap at top including block at wall plate

https://mail.passivehouseplus.co.uk/magazine/upgrade/bungalow-bills#sigProId4460420e60

It was apparent very early on that this was going to have to be a very deep retrofit. Like so many bungalows, the house had two sitting rooms, separated by a chimney breast, on which the roof was structurally dependent.

Taking down the chimney breast more or less meant taking down the roof. Once the demolition phase was over, the house had been reduced to three external walls and the foundation.

All internal walls, along with most of the front wall and the roof had to go.

-

The house stripped back to three external walls and the foundation

The house stripped back to three external walls and the foundation

The house stripped back to three external walls and the foundation

The house stripped back to three external walls and the foundation

-

The new truss roof

The new truss roof

The new truss roof

The new truss roof

-

Roman Szypura explaining the airtightness work to a team from Net Zero Bau

Roman Szypura explaining the airtightness work to a team from Net Zero Bau

Roman Szypura explaining the airtightness work to a team from Net Zero Bau

Roman Szypura explaining the airtightness work to a team from Net Zero Bau

-

Pro Clima Intello Plus vapour control membrane to ceiling

Pro Clima Intello Plus vapour control membrane to ceiling

Pro Clima Intello Plus vapour control membrane to ceiling

Pro Clima Intello Plus vapour control membrane to ceiling

-

Cellulose blown in at high density

Cellulose blown in at high density

Cellulose blown in at high density

Cellulose blown in at high density

-

Thermafleece insulation in service void

Thermafleece insulation in service void

Thermafleece insulation in service void

Thermafleece insulation in service void

-

Insulated supply and extract ducts from MVHR sealed to exterior walls

Insulated supply and extract ducts from MVHR sealed to exterior walls

Insulated supply and extract ducts from MVHR sealed to exterior walls

Insulated supply and extract ducts from MVHR sealed to exterior walls

-

Diathonite cork plaster to window reveals

Diathonite cork plaster to window reveals

Diathonite cork plaster to window reveals

Diathonite cork plaster to window reveals

-

First course of Mannok Aircrete blocks on inner leaf

First course of Mannok Aircrete blocks on inner leaf

First course of Mannok Aircrete blocks on inner leaf

First course of Mannok Aircrete blocks on inner leaf

-

When heat is required, it’s delivered via underfloor heating buried in a screed

When heat is required, it’s delivered via underfloor heating buried in a screed

When heat is required, it’s delivered via underfloor heating buried in a screed

When heat is required, it’s delivered via underfloor heating buried in a screed

-

When heat is required, it’s delivered via underfloor heating buried in a screed

When heat is required, it’s delivered via underfloor heating buried in a screed

When heat is required, it’s delivered via underfloor heating buried in a screed

When heat is required, it’s delivered via underfloor heating buried in a screed

-

Plastic starter rail to reduce thermal bridging

Plastic starter rail to reduce thermal bridging

Plastic starter rail to reduce thermal bridging

Plastic starter rail to reduce thermal bridging

-

New Internorm windows hung on the outside of the wall, sat on Alma Vert structural insulation supports

New Internorm windows hung on the outside of the wall, sat on Alma Vert structural insulation supports

New Internorm windows hung on the outside of the wall, sat on Alma Vert structural insulation supports

New Internorm windows hung on the outside of the wall, sat on Alma Vert structural insulation supports

-

300 mm cavity wall pre installation of bonded bead insulation, with 200 mm KORE EPS70 Silver insulation externally

300 mm cavity wall pre installation of bonded bead insulation, with 200 mm KORE EPS70 Silver insulation externally

300 mm cavity wall pre installation of bonded bead insulation, with 200 mm KORE EPS70 Silver insulation externally

300 mm cavity wall pre installation of bonded bead insulation, with 200 mm KORE EPS70 Silver insulation externally

-

Airtightness taping around windows

Airtightness taping around windows

Airtightness taping around windows

Airtightness taping around windows

-

KORE EPS insulation cut to measure to insulate the eaves

KORE EPS insulation cut to measure to insulate the eaves

KORE EPS insulation cut to measure to insulate the eaves

KORE EPS insulation cut to measure to insulate the eaves

https://mail.passivehouseplus.co.uk/magazine/upgrade/bungalow-bills#sigProId5b1627130e

“In doing that, we saw all the horror shows that you expect to see. We had built-in wall cabinets around the bed, and when they came out, there was mould behind them. And there was mould behind the units in the kitchen. We had sagging insulation in the wall cavities, and when we cracked up the floor, we found insulation that was the thickness of a Curly Wurly.’

The new wall build-up mixes old with new: blown bead into the existing cavity, internal plastering for airtightness, with external wall insulation doing the heavy lifting.

McCarron says he did a lot of agonising over the windows. The cost uplift between the basic passive house option and the Internorm units he eventually chose was in the order of €10,000.

A temperature reading in the children’s bedroom pre retrofit

‘Looking back, I’m delighted that we went for those. Once you see the quality of the product, you can’t unsee it. The handles in particular were so much better than the handles on the cheaper windows.’

The fact that the Internorm units were uPVC aluclad as opposed to timber aluclad was the clincher. The windows were hung on the outside of the original wall in order to help preserve thermal continuity.

‘I didn’t like the notion of putting timber out there, in case there was any unintended water at play at sometime down the road.’

Decrement delay and overheating

The build-up in the new pre-manufactured truss roof is also worth highlighting. McCarron points out that rooms in roofs – where the children’s bedrooms are now situated – are vulnerable to overheating. His build-up seeks to mitigate that risk through decrement delay: reducing the time it takes for external heat to transfer into the house. There’s no less than three tons of cellulose insulation in the roof. It’s got more mass than lightweight, petrochemical- based insulations, so it acts like a sink, absorbing the heat from the sun rather than transmitting it into the space.

‘We also have five Velux windows in the house. They were deliberately chosen so that we could purge ventilate the house if we needed to. Over years of observing passive house projects, I’ve seen that a roof light is an excellent way of cooling the building if it did have an overheating issue, which fortunately we don’t.’

These units are five-glazed – a cassette of triple glazed and another gap of double glazed, and remote controlled. Interesting to note too that PHPP modeling prompted a reduction in glazing at the front of the house, and the removal of additional Velux windows from an early version of the plan – again to reduce overheating risk.

McCarron’s children Daithí, Dylan and Doireann during the build

So far so good: after one summer in the house, air temperatures never climbed above the 25 C threshold. Staying with PHPP, McCarron notes that the process of designing and building his own house opened his eyes to the power of passive house software.

In the old house when you got out of the bed you would have [had to] hop, skip and jump to the bathroom because it was so uncomfortable. Now when you put your foot onto the tile it isn’t cold. The underfloor heating hasn’t been on yet

‘A lot of people in the construction industry think of them as compliance tools, they think in terms of ‘What’s my score?’ Really, PHPP is a tool that helps you evolve the design of the house. It took me a couple of years on my journey to learn that properly. To see the impact of that in my own house was really great, because every decision was educated and backed up by evidence.’

The other big advantage of using so much timber-based insulation was a reduction in the building’s embodied carbon score, in particular in the case of the cellulose insulation.

Because of life cycle assessment rules, this has little or nothing to do with CO2 stored in the materials, but all to do with the fact that products like cellulose require remarkably little energy and associated CO2 to manufacture.

“Obviously, when you have a retrofit, your embodied carbon is going to be part of the story because you’re keeping much of the existing structure and you’re not building in a greenfield site, but when you start to use cellulose or wood fibre, you’re going to do so much better.”

He notes too that choosing natural materials didn’t have any adverse impact on cost.

McCarron using a thermal imaging camera phone in the finished home.

Exceeding airtightness ambitions

Achieving airtightness in a retrofit is often a major challenge, but thanks to careful detailing and support from professionals, the team achieved the Enerphit standard on the first attempt, with 0.69 air changes per hour (ACH) – well inside the 1 ACH threshold, and right on the cusp of the 0.6 ACH threshold required by passive house.

‘Roman (Szypura of Clioma House, who did the blower door test) rang me at the time and said, “Well done, Barry. You’ve got Enerphit. It’s a passive house retrofit. But this is a bad result for you because now you have to go after a full passive house.”’

At the time, the heat load in the retrofitted house had been reduced to 10 W/m2 – which meets the heat load target for the passive house standard. This meant that if McCarron could secure a small improvement in airtightness, he would achieve full passive certification for the project.

The airtightness team carried out some remedial work around screw holes in kitchen units and junctions where the old structure met the new, and a second blower door test confirmed that the target had been met. Now, remarkably, the retrofit meets the full passive standard.

As part of the process of seeking passive house certification, the project had to be meticulously documented throughout, primarily by taking photographs at every stage. That’s what put the idea in McCarron’s head: start an Instagram account and share the experience of building passive with the wider self-build community.

‘It was one way of making sure I didn’t drop off on the homework, so every Friday, I did a post, I wrote something up and I put up the photographs. That really kept me on track.’ It also proved to be very popular, and over the months of the build, picked up over 3,700 followers (@bungalow_retrofit). It was, he says, a very rich and positive experience.

‘There is a huge thirst for independent information out there…That whole Instagram self-build community bouncing off each other, asking questions – it’s amazing how fertile it is. Of course, the danger is that there are also people out there who are not construction experts communicating things that may not be right.’

As it happens some bona fide construction experts communicated that things are most definitely right with this project, with the house picking up the housing award at the Towards Net Zero Awards in November.

McCarron pays tribute to the range of construction professionals that worked with him on the project, including Ryan Daly of Daly Renewables, Roman Szypura of Clioma House, and Seamus Keenan of Positive Energy Ireland, as well as his contractor, Owen Treanor. ‘He was excellent. He was really open and open minded. He had never built a passive house before, but he kept listening. And he kept an open mind.”

As Passive House Plus often hears from builders who have built their first passive house, Treanor says the process has changed him.

“Definitely,” he says. “It has given me a whole new way of thinking in terms of junctions and detailing and even in terms of minimising waste. I’m working on new extensions now, and the detailing from Barry’s house is being used again.” Even while still on site with new projects, Treanor can see signs of the benefits his clients will reap. “The heating isn’t on in the extension yet and it’s warmer than the house.”

Treanor says McCarron’s efforts to minimise waste on this project has encouraged him to the opportunities to reduce waste disposal costs. This project arguably blurs the line between a new build and a retrofit, but 25 per cent of the existing building was retained, including 66 per cent of the existing walls. “All rubble and concrete waste went to a project about 400 m from our site to another site for hard standing and back fill,” says McCarron.

With waste disposal costs becoming an increasing issue, Treanor points to less progressive approaches to construction and demolition waste. “I remember a builder saying a hole is a very handy thing,” he says, while pointing out that a more circular approach can avoid costs on waste disposal and on acquiring new materials.

Moving back in

The family moved into the house in May and are loving the new space. While the look and feel of the house has been transformed, the design team retained that original bungalow profile. Inside, the double height ceilings in the main living area belie what we’ve come to expect when we walk through the front door of an Irish bungalow. It’s bright and airy, with consistent temperature and perfect indoor air quality.

Having suffered the house’s discomfort before the retrofit, McCarron is acutely aware of the palpable change in living conditions.

“One of the great experiences of living in the house so far has been when you get up in the middle of the night. In the old house you would have got out of the bed and you would have [had to] hop, skip and jump to the bathroom and back because it was so uncomfortable,” he says. “Now you just get up, and what really strikes you is when you put your foot onto the tile, the tile isn’t cold. The underfloor heating hasn’t been on in the house yet. We’re now 12 October. This morning was the first day with frost and still this morning I would have got up about 5am to go to the toilet and the tiles aren’t cold underfoot. That level of comfort’s there even without the heat.”

While healthy adults may be able to grin and bear the discomfort of typical houses, it’s a different matter for vulnerable occupants such as people with disabilities, elderly people or young children, whose health is more likely to suffer in suboptimal living conditions.

“Doing passive was directly linked to the family motivations,” he says, referring to his three children, Doireann, Daithi and Dylan. “For myself and Aisling it was: do this now for them really to get the good out of it from when they are young.”

My bald head is fantastic for picking up drafts. In our old living room, with the stove on, my face would be melted but the back of my head would be frozen

The focus was very much on the living conditions his children would experience growing up, and how it might affect their development. “Doireann is seven, Daithi is five and Dylan is three, so that’s 11, 13 and 15 years of excellent indoor air quality levels respectively till they turn 18 – sleeping and living in CO2 levels below 800 ppm.”

One issue McCarron thought long and hard about was kitchen extraction. As Passive House Plus has previously reported, a number of potentially harmful pollutants can be released during cooking, meaning effective air extraction becomes essential. McCarron opted for a recirculating extractor - in light of a paper at the 2023 International Passive House Conference showing reasonable extract coverage for recirculating extractor hoods. But in this case the extractor is integrated into the hob. With ventilation experts tending to recommend overhead extractors, McCarron added two extracts for the MVHR system above the cooker too, and is replacing filters every three months.

So far so good, he says.

For McCarron, in light of the comfort and energy benefits families can reap in such high performance homes, the decision to go passive should be a no brainer.

“My advice for anyone, if you’re building a new build or you’re retrofitting would be to go the whole hog and to do the passive house thing. I’m forty years of age, and my only regret is I should have done it ten years earlier, instead of procrastinating. And always build to the best standard that you can at any given moment. I don’t think you’ll ever regret it.”

Embodied carbon

The McCarrons’ house is about as deep as a retrofit can be, and could almost be considered a new build, given that the floors were dug out and the building stripped right back to the walls. The RIAI 2030 Climate Challenge differs from the RIBA equivalent which inspired it in one key regard for this project. While the target for smaller dwellings is 625 kg CO2e/ m2, for dwellings over 133 m2, and low density dwellings of up to two storeys, that target is reduced to 450 kg CO2e/m2 – reflecting the fact that large one off houses tend to bring additional environmental burdens.

An indicative analysis of the bungalow’s embodied carbon carried out using PHribbon showed that the building hit 80.5 tonnes of CO2e – or 454 kg CO2e/m2, narrowly missing the RIAI 2030 target for this house.

The biggest contribution came from the building’s concrete products and large PV array, though it’s worth noting that default data for materials was used in both cases. When assessed against LETI’s embodied carbon targets, the building scored 294 kg CO2e/ m2 in terms of upfront emissions – meaning up to the point of the building’s practical completion. As per LETI’s approach for upfront emissions, this figure doesn’t count the sequestered (or stored) CO2 in the biogenic products used like timber, wood fibre and cellulose, and it also excludes the PV, as LETI regard PV as part of the grid rather than the building, except in cases where the PV array forms part of the roof structure, such as building-integrated PV. The cradle-to-grave LETI total only marginally increases to 298 kg CO2e/m2.

This is for a couple of reasons: the benefit of the sequestered CO2 in the biogenic materials is effectively cancelled out by the assumption those emissions are released into the atmosphere at the end of life of the building. And the assumed carbonation of the building’s concrete products at end of life adds a small amount of permanent sequestration to the results.

Selected project details

Client: Barry & Aisling McCarron

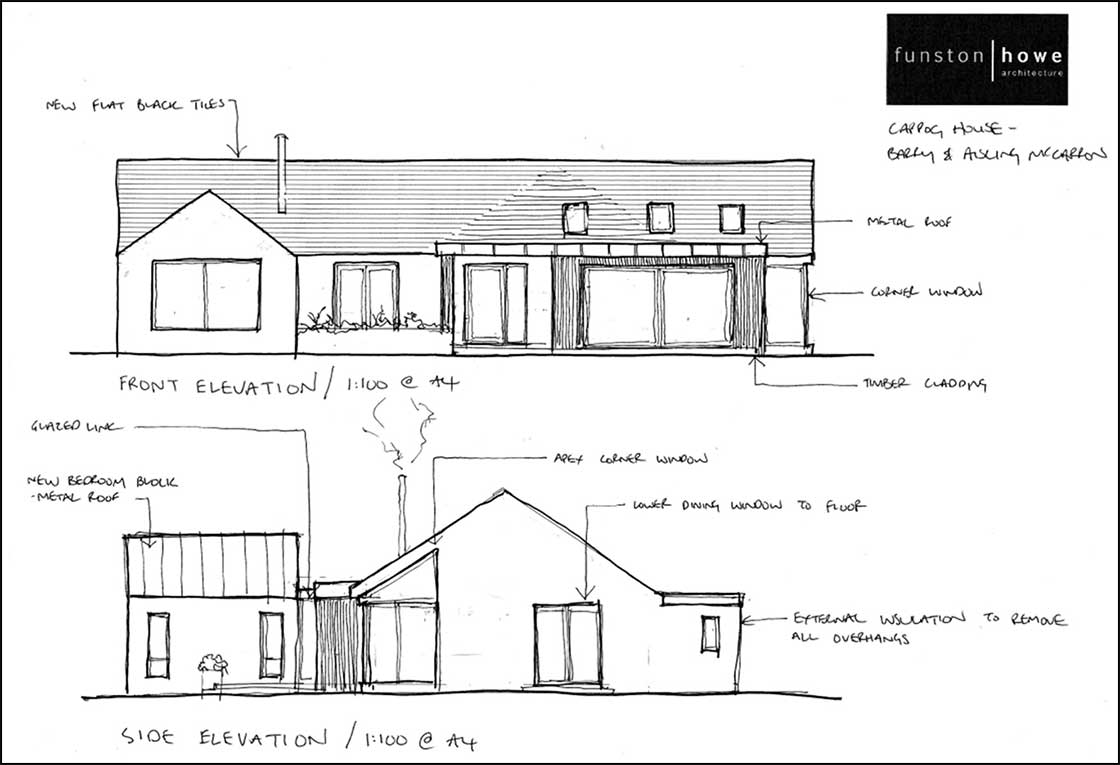

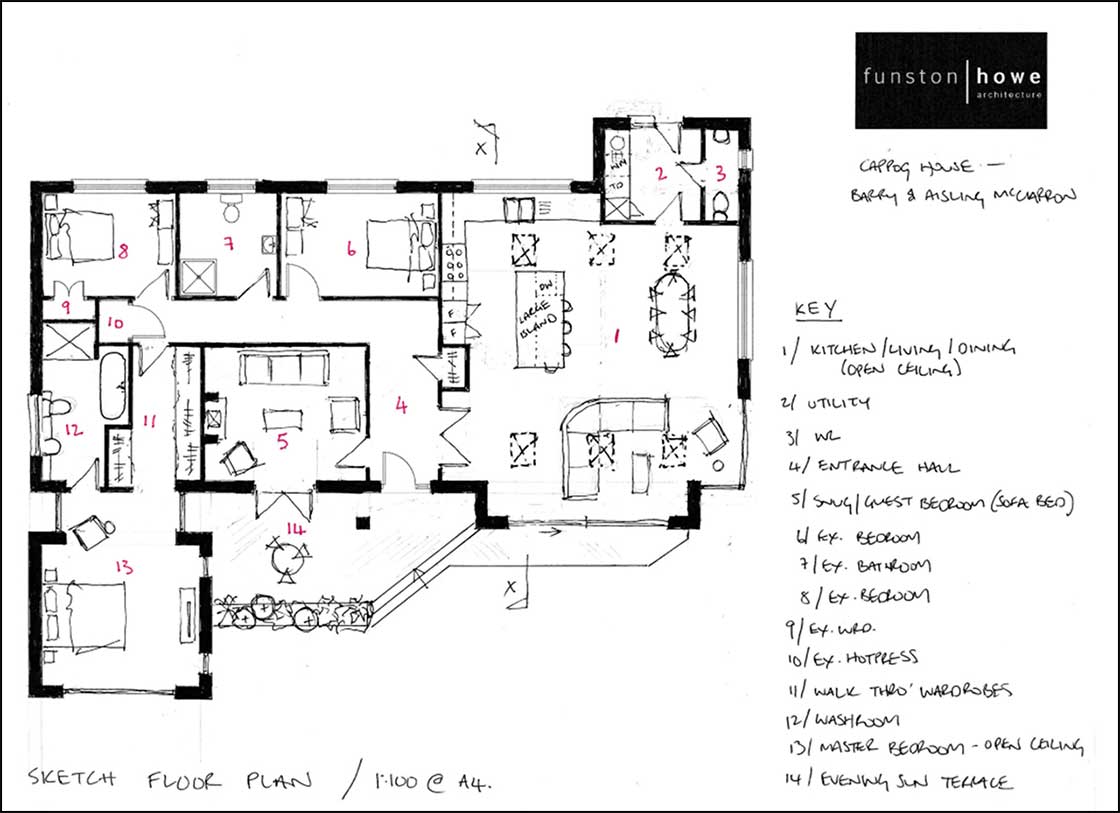

Architect/engineer: Wayne Funston, Funston Howe Architecture

Mechanical and electrical: Daly Renewables

Passive house certification: MosArt

Project management: SustainABLE

Builder: Owen Treanor Construction

Electrical: Positive Energy Ireland

Airtightness: Atlantic Air / Greenbuild

Passive house certifier: MosArt

Home Performance Index assessment: Wain Morehead

EPS/XPS and cavity fill: KORE Insulation, via Breffni Insulation

External insulation system: Sto

Aerated blocks and roof tiles: Mannok

Thermal breaks: Partel

Airtightness membrane, cork plaster, woodfibre, cellulose and wool insulation: Ecological Building Systems

Cellulose and airtight membrane installer: Clíoma house

Airtight tapes: Ecological Building Systems / Partel

Windows and doors: Internorm via Interlux

Roof windows: Velux

Air source heat pump: Eco Forest, via Daly Renewables

Underfloor heating: Roth, via Daly Renewables

Heat recovery ventilation: Renson, via Daly Renewables

Lighting: Mullan Lighting

Sand/cement screed: Micheal Heeney Flooring

Interior design: Mags McCarron, Your Home Illustrated

Furniture and carpet: Upstairs Downstairs

Tiles: Irwins Castleblaney

Water conserving fittings: Grahams Hardware Monaghan

Sanitaryware: My Life

Heat pump: Ecoforest EcoAir PRO 1-7kw ASHP, via Daly Renewables

In detail

Building type: 138 m2 1969 bungalow retrofitted and extended to 188 m2

Site & location: Ballinode Village, north county Monaghan

Completion date: April 2023

Budget: €360,000 / €1,925 per m2

Passive house certification: Passive house classic (pending)

Embodied carbon total: 422 kg CO2e/m2 (when assessed as per RIAI 2030 Climate Challenge, including modules A, B1-B5, and C)

Green building certification: Home Performance Index (pending)

Space heating demand (PHPP): 27 kWh/m2/yr

Heat load (PHPP): 10 W/m²

Primary energy demand non-renewable (PHPP): 87 kWh/m2/yr

Primary energy demand renewable (PHPP): 50 kWh/m2/yr

Renewable energy generation: 27 kWh/m2/yr

Heat loss form factor (PHPP): 3.9

Overheating (PHPP): 1 per cent

Number of occupants (PHPP): 5.0 for passive house assessment.

Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.57m3/hr/m2 at 50 Pa / n50 of 0.53

Thermal bridging: First course of Mannok Aircrete blocks on new inner leaf walls, windows and doors bracketed into external insulation line sitting on Alma Vert structural insulation supports/thresholds, cork plaster to the window reveals.

Ground floor: 100 mm sand and cement screed, followed underneath by 180 mm PIR insulation, U-value: 0.11 W/m2K

Walls: 300 mm traditional cavity wall construction with 100 mm KORE Fill insulation in cavity, 200 mm KORE EPS70 Silver insulation, StoMIX EWI System. U-value: 0.10 W/m2K

Roof: Mannok concrete tiles, timber batten, Pro Clima Solitex membrane, Gutex wood fibre insulation, Dämmstatt cellulose insulation, Pro Clima Intello airtightness membrane, Thermafleece sheep wool insulation, 50 mm service void/air gap, U-value: 0.125 W/m2K

Windows & external doors: Internorm KF410 UVPC Aluclad. Passive House Institute certified. Overall U-value of 0.84 W/m2K

Roof window: Velux certified passive house roof light

Heating: Ecoforest EcoAir PRO 1-7 KW modulating air source heat pump, with low temperature heat delivered via underfloor heating.

Ventilation: Renson Endura Delta mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) system. Passive House Institute certified heat recovery efficiency of 84 per cent.

Electricity: 5.92 kWp photovoltaic array. Excess energy is used for electric car charging or grid export.

Image gallery

-

Detail at eaves

Detail at eaves

Detail at eaves

Detail at eaves

-

Detail at floor level

Detail at floor level

Detail at floor level

Detail at floor level

-

Detail at window cill

Detail at window cill

Detail at window cill

Detail at window cill

-

Detail at window head

Detail at window head

Detail at window head

Detail at window head

-

Detail at window jamb

Detail at window jamb

Detail at window jamb

Detail at window jamb

https://mail.passivehouseplus.co.uk/magazine/upgrade/bungalow-bills#sigProId911bff02f5