- International

- Posted

International: Issue 25

A selection of passive & eco builds from around the world, this issue features a boat designed according to passive house principles, with the artic climate in mind, and a contemporary passive house by Key Architects on Japan’s rural Shikoku Island.

Masaki Passive House

Shikoku, Japan

Key Architects are rapidly gaining a reputation as Japan’s leading passive house design firm, and first came to the attention of Passive House Plus with their stunning Tochoji Temple in Tokyo, which we featured in issue 22. Their latest passive house project is a contemporary dwelling in Ehime prefecture on Japan’s rural Shikoku Island, boasting a wide-open southerly orientation and stunning views over the adjacent farmland towards the wooded peaks beyond.

And wood is at the heart of this striking contemporary dwelling: the plywood-framed walls are insulated with woodfibre, and timber cladding also features heavily. Meanwhile the windows are made of aluminium-clad timber, and the house’s main source of space heating is a stove that burns wood logs.

Because Shikoku’s climate is warm and temperate, with daytime temperatures averaging 27.5C in August, the house didn’t need as much insulation as a typical passive house in northern Europe — U-values for the walls range between 0.18 and 0.21, for example (less than 0.15 is the norm for the UK and Ireland).

The thick clay that forms the external leaf of the walls also helps to buffer moisture in the humid local climate, while providing airtightness without the need for membranes. And a solar thermal array located beside the vegetable garden also helps to provide for space heating and hot water.

Considering all of that, it’s no surprise the house won Japan’s third annual Eco House Design Award in 2017.

The Nanuq

Passive house boat

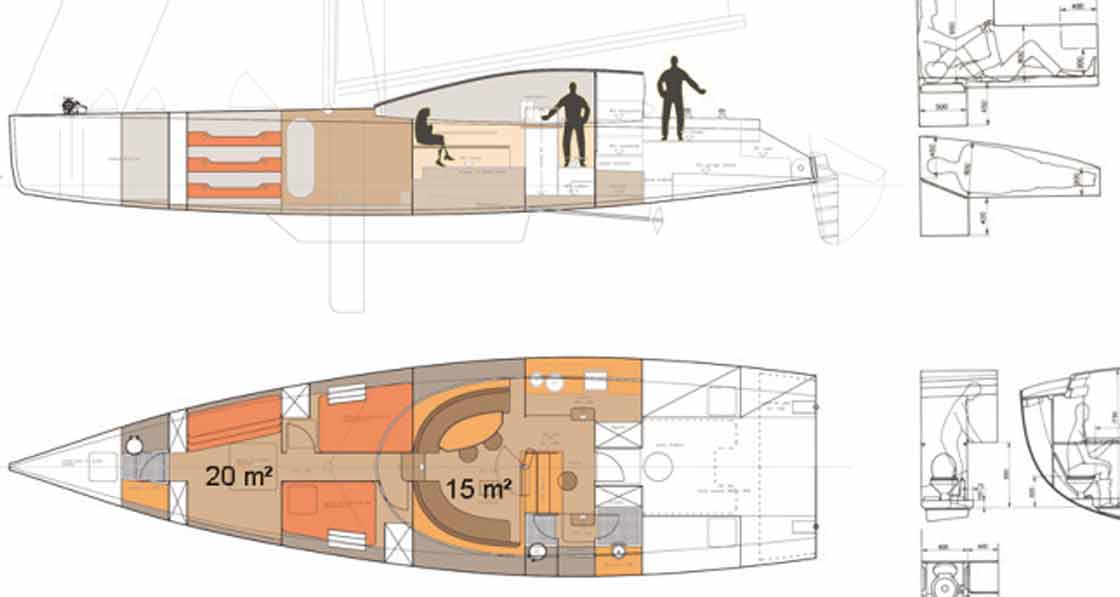

Designed, built and skippered by Swiss architect Peter Gallinelli, the Nanuq is a 60 foot sailboat intended to serve both as a scientific base and accommodate a team of six through an arctic winter.

This article was originally published in issue 25 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

And with the arctic climate in mind, the cabin that sits at the heart of the boat is designed according to passive house principles — Gallinelli calls it his ‘passive igloo’.

Gallinelli’s aim was to design a boat that would allow him to comfortably “pass through an arctic winter in a self-sufficient dwelling without the use of non-renewable energy”.

The project was inspired by Norwegian explorer Fridthof Nansen’s legendary 19th century boat Fram, which — with its oak frame, cork insulation and triple glazed windows — is often regarded as an early example of passive design.

The igloo at the core of the Nanuq is constructed from a frame of fibreglass and epoxy resin skins sandwiching a core of high performance polystyrene insulation, giving the cabin walls a passive level U-value of 0.12.

Triple glazed windows feature too, while the completed ‘igloo’ weighs only 1,300kg and can be dismantled into five easily transportable parts. And just like a passive house, the boat also features a heat recovery ventilation system, albeit an experimental version tailored for the particular stresses of the arctic conditions. Incoming fresh air from outside — which is often colder than -30C in winter — is first preheated by the relatively balmy seawater (at about -2C) in a submerged tube, before entering a marine grade heat exchanger. Care was required to prevent the heat exchanger icing up, with water from condensation being directed into a bottle, while the air outlet also had to be adapted to prevent blocking by the formation of ice.

A 1.5 kW wind turbine combined with four solar PV panels – which contributed nothing between the sun setting for winter in October and rising in February – power the boat, with a back-up diesel generator, and every effort was taken to reduce electricity use to a minimum of just 0.5 kWh per day – for a boat serving 2.5 occupants.

In order to test the performance of the passive igloo, the boat was voluntarily trapped in sea-ice in north-west Greenland during the winter of 2015-2016 and monitored during 10 months of ‘stationary navigation’.

According to Gallinelli, the biggest unforeseen difficulty was the unexpected lack of wind during the arctic winter, which meant the boat had to rely on a back-up forced air diesel heater for heat rather than wind-powered direct electric heating. Gallinelli notes that a heat pump, which was omitted for budgetary reasons, would have provided 100% of thermal comfort needs during a more typical arctic winter.

Still, the boat used just 330 litres of diesel over the winter — ten times less than average homes in the region.

Powered passively by the wind, the Nanuq will venture northward again this summer as part of PolarQuest 2018, a scientific mission to measure the impact of human pollution in arctic waters, assess the impact of micro and nano plastics in the region, and study the origin of high energy cosmic rays and their impact on global warming.