- International

- Posted

International selection - issue 15

The Living Building Challenge is arguably the world’s toughest environmental building certification program. In order to achieve the award, buildings must meet rigorous standards in seven different performance categories, also known as ‘petals’: place, water, energy, health and happiness, materials, equity and beauty. Our selection includes three American buildings that have been certified to one of these standards.

This article was originally published in issue 15 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

____________________________________________________________________

Packard Foundation Headquarters,

Los Altos, California

Photos: Jeremy Bittermann/Terry Lorant

The David and Lucile Packard Foundation in Los Altos, California is a philanthropic group dedicated to solving the world’s most intractable problems. The foundation’s new headquarters employs passive, bioclimatic design strategies that support this core philanthropic mission, achieving both LEED Platinum and Living Building Challenge net zero energy certification. It is also the largest net zero energy office building in California, and aims to demonstrate how an organisation can improve its effectiveness and the quality of life for its employees while drastically cutting carbon emissions.

The building was constructed from a wood and steel hybrid structure, employing FSC certified timber, and low carbon concrete for the foundations. It also features a 291 kW solar PV system. Individual branch circuit monitoring is employed so that the energy consumption of each load can be pinpointed and pieces of equipment which consume large amounts of power can be easily identified. The building design, consisting of two long, narrow wings surrounding a centre courtyard, reduces energy consumption by maximising daylighting. Light shelves project natural light farther into space and reflect it off the ceiling, diffusing daylight throughout the space.

Naturally, the design team paid careful attention to material selection too: wood veneer was sourced from eucalyptus trees felled at a construction project in San Francisco, exterior wood is FSC-certified western red cedar, while stone is from Mt Moriah on the border of Utah and Nevada, all within a 500-mile radius from the site. The exterior copper is 75% recycled, with a long life span and integral finish. And the building apparently uses a total of 74 kWh/ m2/yr in energy, but produces even more than that through solar power, ensuring it achieved net zero energy certification.

Phipps Centre for Sustainable Landscapes

Pittsburgh

Photos: Paul G Wiegman/dllu

Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Garden’s mission is to inspire and educate people about the beauty and importance of plants, advance human and environmental wellbeing, and to celebrate its historic glass houses. All three goals are evident at the Centre for Sustainable Landscapes (CSL) in Pittsburgh, which is a fully certified Living Building, and provides office, classroom, research and library space for the group.

The building is of concrete and steel construction with a wood façade and metal frame windows. It consumes 57 kWh/m2/yr of energy, but produces slightly more from its 125 kW solar photovoltaic array.

A green roof has also been installed to reduce the heat island effect. Mechanically, the building is primarily served by an underfloor air distribution system that introduces fresh air into the building. When outside air conditions permit, the building is cooled by natural ventilation through motorised operable windows.

Meanwhile, geothermal wells feed water cooled compressors for both heating and cooling loads, providing preheated water to the air handling unit in the winter and cool water during the summer. Rainwater is captured from not only the CSL site but the substantial rooftop space of the adjacent Tropical Forest Conservatory.

The facility is located on the Phipps campus’ southwest corner, nestled into the hillside on a remediated brownfield lot once used as Pittsburgh’s Department of Public Works storage facility and service yard. The site had been paved over several times and suffered decades of environmental devastation.

Indigenous, sustainable plants and soil were brought in to rebuild the hillside nearly from scratch. Today, a terraced garden leads downhill from the roof to the ground floor of the centre, allowing visitors to walk a trail of native plant communities, including wetlands, oak woodlands and upland groves.

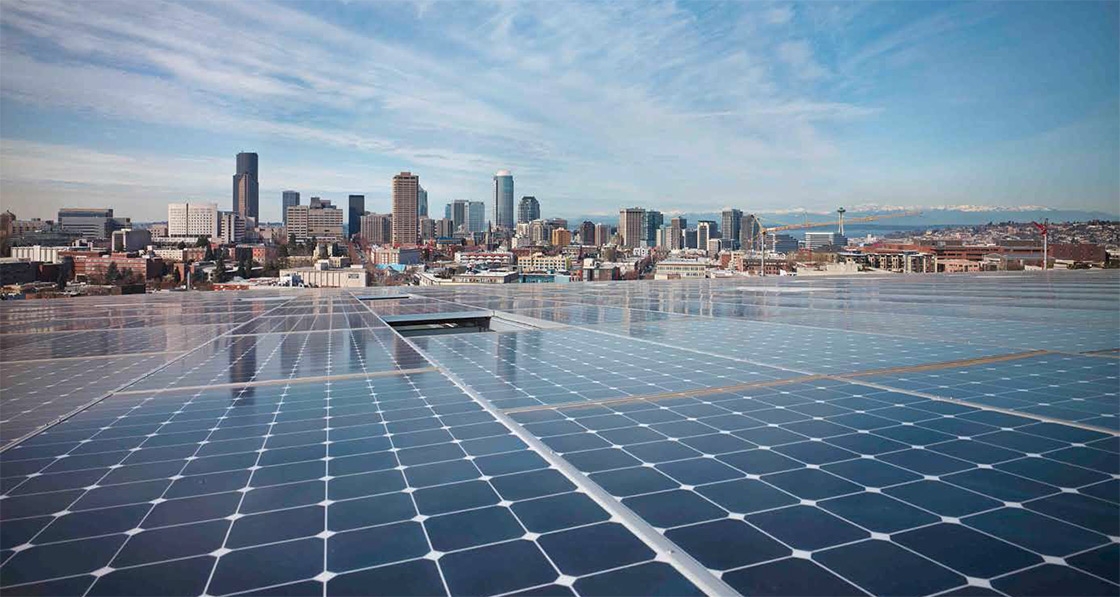

Bullitt Centre,

Seattle, Washington

Photos: Nic Lehoux

Backed by its mission to protect the Pacific Northwest’s natural environment and promote healthy and sustainable ecosystems, the non-profit Bullitt Foundation wanted its new headquarters to achieve the highest level of sustainability. The foundation also wanted the building to be a demonstration project that would set a new standard for developers, architects, engineers and contractors, so decided to aim for the Living Building Challenge, and the building achieved full certification to the standard.

The new centre is a six-storey commercial office building, powered by a 244 kW rooftop solar array composed of 575 PV panels. All rainwater that falls on the site is collected in a cistern in the basement, treated to potable drinking standards,which supplies all the water needs of the building. Meanwhile the centre’s six-storey composting toilet system creates a usable fertiliser at the end of its process. The building is a type-IV heavy timber structure, made of Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified glulam beams and dimensional lumber, and insulated with formaldehyde-free fibreglass that employs a plant-based binder material. The 4719 sqm centre reports a total energy consumption, not accounting for renewable electricity production, of 152,877 kWh/m2/ yr, which – including a health warning, as the building’s usage is helped by the fact it wasn’t fully rented during monitoring – translates to just 32 kWh/m2/yr in delivered energy use. According to the US EPA, the average primary energy factor of US electricity is 3.14 – meaning that if the quoted figure is 32 kWh/m2/yr of delivered energy, it would translate to just over 100 kWh/m2/yr of primary energy. But, as Bullitt Foundation’s president Denis Hayes points out, the electricity generation mix in Seattle is very different to the national average, consisting of 89.3% hydro, 4.3% nuclear and 3.6% wind, with coal, landfill gas and other sources collectively contributing just 2.5%.

When the energy generated by the building’s massive solar PV roof is taken into account, the building is a net energy contributor. The 152,877 kWh/m2/yr total consumed during the building’s assessment period for the Living Building Challenge – credited to a combination of the building’s efficiency and engagement from occupants – is dwarfed by production of 243,671 kWh, a surplus of nearly 90,000 kWh. The building exports surplus electricity to the grid for eight months of the year, only becoming a net importer from November to February. “In the four importing months, the hydropower reservoirs are full to overflowing and the utility is delighted to have increased demand that it does not have to export,” says Denis Healy. “In the summers – which are getting warmer every year – we are comfortable without the air conditioning found in every other office building in town, and we generate huge electricity surpluses at precisely the time of year and the time of day when the utility most wants them.” The centre sits atop a ground-source heat pump system tapping into 26 wells, each reaching a depth of 121 metres.

All materials used in the building were screened for compliance with the Living Building Challenge’s materials red list to restrict toxic chemicals. The building’s ecological features are now shared with the public through an ongoing tour program, a public exhibition space, and a number of research projects all managed by the University of Washington’s Integrated Design Lab.