- International

- Posted

International selection - issue 18

This issue features the world’s smallest certified passive house in France, and the first certified passive house on New Zealand’s South Island.

This article was originally published in issue 18 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Mizu Project, Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, France

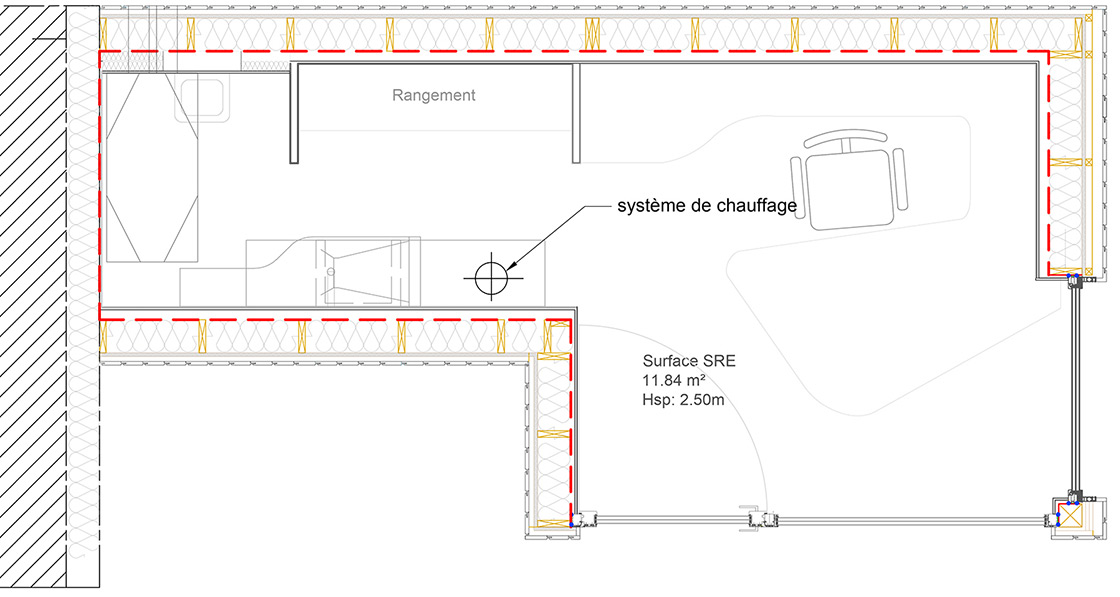

This tiny office, dubbed ‘Mizu Project’, is the smallest certified passive house of any kind in the world at just 12 square metres. It was designed and built by engineer and passive house consultant Thomas Primault, who runs his consultancy Hinoki from the building near the city of Rennes in north-west France.

Photos: David Montigny

“The architecture is a tribute to Japanese tea houses, and the principles of minimalism, simplicity and naturality,” he says of the building (Mizu means water in Japanese).

Primault built the structure out of his need for a space in which to work comfortably, and meet his clients. Keen to both live and work in the countryside, he built the office right up against his own home amid the fields and woods of rural Brittany.

But building a passive house this small posed challenges — its tiny volume meant it had a relatively large surface area from which heat could escape, and from which air could leak. This made achieving the heat demand and airtightness targets of the passive house standard tough.

Ultimately, he built the structure from a lightweight timber frame of local wood, insulated with cellulose and Pavatex Pavaflex wood fibre – with Pavatex Isolair sarking boards – and for the floors he used Porextherm Vacuspeed vacuum insulated panels, which offer excellent insulation for low thickness, thus allowing more head space inside. Windows and doors are thermally broken triple-glazed timber-alu clad systems, with Unilux Design Line window and entrance door on the patio-facing south façade and an Internorm Varion window on the east façade. He also lifted the entire lightweight building off the ground to cut thermal bridging, and wrapped the whole interior of the structure in Pro Clima airtightness membranes.

But the airtightness test also posed a challenge — no blower door machine small enough to test the building properly was available. So instead, Primault used a machine normally employed to test air leakage from ventilation ducts (and the building scored 0.4 air changes per hour).

And while at first he wanted to heat the office only with his kettle, he did find the office a little cool on winter mornings, so ultimately installed a heating diffuser on one of the Helios heat recovery ventilation system’s intake ducts. One interesting innovation: the interior walls are plastered in Enerciel phase change material to offer something approximating thermal mass.

Primault reckons the whole project cost in the region of €25,000.

George House, Wanaka, South Island, New Zealand

Photos: Simon Devitt

Photos: Simon Devitt

Designed by architect Rafe Maclean, George House is the first certified passive house on New Zealand’s South Island (there are seven more on the North Island). Maclean’s clients had heard about passive house while watching an episode of Grand Designs, and got hooked on the idea. So they knocked the existing 1950s house on the site in the resort town of Wanaka, and appointed Maclean to design this elegant new passive house.

It was Maclean’s first passive house, and he admits it was a “steep learning curve”. The new 141 square metre home was built with structural insulated panels added to an insulated timber stud, and scored an airtightness test result of 0.57 air changes per hour. Ventilation is provided by a Zehnder Comfoair MVHR system, with triple-glazed Schweikart windows. Its roof also boasts a solar PV array, which helps to power the electric panel heaters inside.

Completed in June 2015 and certified by Ireland’s globetrotting Passive House Academy, the house experienced outdoor temperatures of -10C outside during its first winter, but maintained a comfortable 20-22C inside. “The clients are super happy with the result, the design and the building performance,” says Maclean.

Last year over 200 people came to visit the house over a three hour period during November’s international passive house open day. “Which played havoc with internal heat gains,” Maclean says.

He adds that the homeowners are still happy to show anybody around the house, as they are “keen on spreading the message that this is the way to build”.

And despite the challenges of the build, Maclean and his builder Issac Davidson have become a certified passive house designer and tradesperson respectively since the house was finished, while the house also picked up the southern architecture award at 2016’s New Zealand Architecture Awards.

Image gallery

Passive House Plus digital subscribers can view an exclusive image gallery for this article